Limerick Clean Energy Center

Nuclear: An Ideal Foundation for Our Clean Energy Future

Limerick Clean Energy Center's two nuclear reactors in Pottstown, Pennsylvania can produce up to 2,317 megawatts (MW) of clean, carbon-free energy, enough electricity to power the equivalent of more than 1.7 million homes. Limerick sits on a 600-acre site and draws its cooling water from the Schuylkill River.

- License Renewal

U.S. nuclear energy facilities are initially licensed to operate for 40 years and a Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) rule allows licensees to apply for initial and subsequent license renewals of up to 20 years each after the initial 40-year term. The NRC approved initial license renewal for Limerick on October 20, 2014, authorizing operation for Unit 1 and Unit 2 through 2044 and 2049, respectively.

- Safety First

Safety is Constellation’s first and most critical obligation. Nuclear power plants are among the best-protected private sector facilities in America, with monitoring and inspections by plant owners, local officials, and the federal government.

Learn more to learn more about the measures that we take to keep our employees, customers, and communities safe.

Emergency Planning for the Limerick Area

Planificación de emergencia para el área de Limerick

- Supporting the Local Economy

Limerick Clean Energy Center has been part of the Pottstown community for decades, providing hundreds of well-paying jobs and millions of dollars in economic support, including about $5.3 million in taxes annually for schools, roads, and other public services.

Limerick Clean Energy Center is referenced in legal and regulatory filings as Limerick Generating Station.

Useful Links

About this facility, pottstown, pennsylvania 19464, related articles.

Constellation’s 2024 Sustainability Report Showcases Work To Advance Clean Energy Future, Uplift Communities

Constellation's ‘Fishing for a Cure’ Raises $70,000 for Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

Former Miss America Grace Stanke Begins Career as Nuclear Engineer and Advocate At Constellation

Constellation Seeks License to Operate Dresden Clean Energy Center for an Additional 20 Years

Moody’s Upgrades Constellation’s Credit Rating as Policy Support and Growing Demand for Clean Energy Fuel Strong Financial Performance

Power Plant Productions

230 N 2nd Street, Philadelphia, PA

About This Vendor

Amenities + details.

Pricing for Power Plant Productions

- Top reviews

- Newest first

- Oldest first

- Highest rated

- Lowest rated

Contact Info for Power Plant Productions

- 301 or more

- Messaging our verified vendors on The Knot is free, safe and secure.

- Conveniently track vendor messages and planning details all in one place.

- Our mobile apps make it easy to stay in touch with vendors while you're on‑the‑go.

- For personalized pricing and package details, sending the vendor a message is the fastest way to get info.

Wedding Vendors in Philadelphia

- Wedding Vendors /

- Wedding Venues /

- Pennsylvania Wedding Venues /

- Philadelphia Wedding Venues /

- Our Firm Open × Close

- Portfolio Open × Close

- Contact Open × Close

- Investors Open × Close

The Battery

Lubert-Adler acquired the former 500,000 square foot ‘Delaware River Generating Station’ Power Plant, plus an adjacent 6 acres, in November 2019.

The Power Plant – which is located in a Qualified Opportunity Zone – is currently being adaptively re-purposed into luxury apartments, class A office space, food & beverage venues, parking spaces and a plethora of waterfront amenities.

The Battery is expected to create a workplace and housing campus experience on the Delaware River, adjacent to the heart of Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood.

Investment Type

- Home Design Experts

- Senior Living

- Wedding Experts

- Real Estate Agents

- Private Schools

- 50 Best Restaurants

- Be Well Philly

- Find a Dentist

- Find a Doctor

- Life & Style

- Properties & News

- Find a Home & Design Pro

- Find a Real Estate Agent

- Events in Philly

- Philly Mag Events

- Guides & Advice

- Find a Wedding Expert

- Bubbly Brunch Event

- Best of Philly

- Newsletters

If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

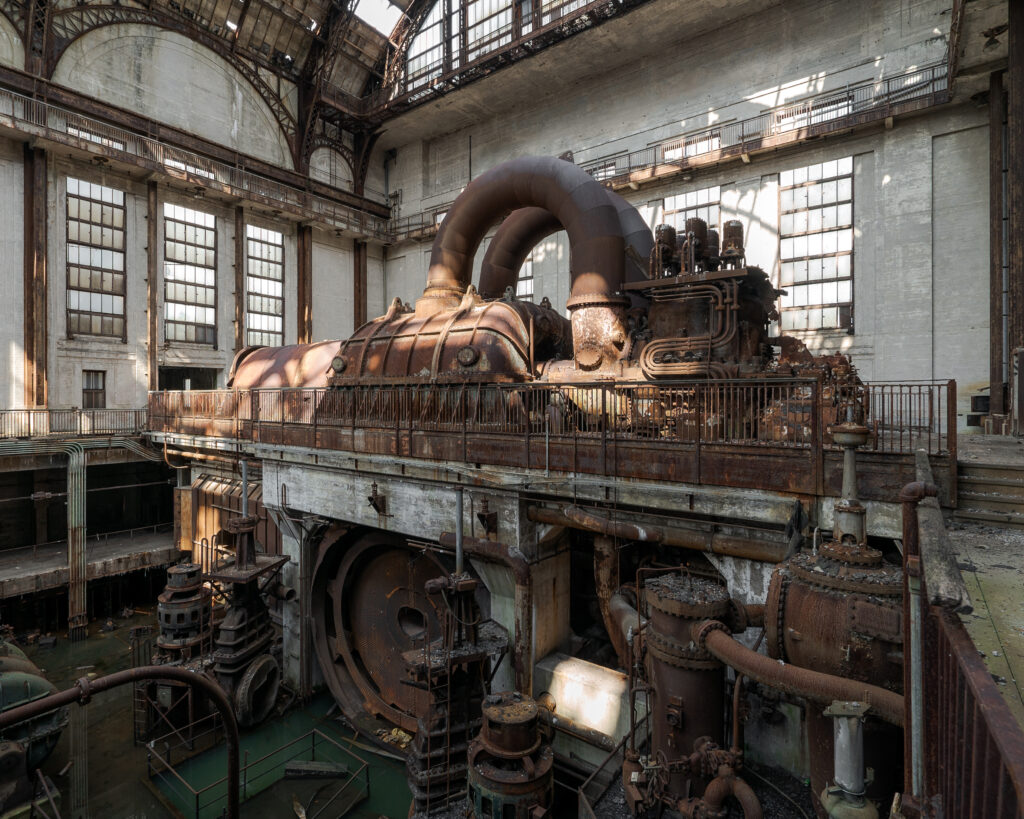

Inside the Plan to Bring New Energy to the PECO Power Station on the Waterfront

A long-dormant power station on the Delaware — a tattered icon of our industrial past — is being reborn as luxury apartments. Are we finally figuring out how to embrace, rather than knock down, our architectural heritage?

Sign up for our weekly home and property newsletter, featuring homes for sale, neighborhood happenings, and more.

A rendering of the proposed rooftop pool at the Battery. / Courtesy of NQS Creative

They’re keeping the smokestacks.

The eight 167-foot-high chimneys of the former PECO Delaware Generating Station haven’t barfed out noxious exhaust from coal that’s burning to make electricity since the place was switched off around 1975. The stacks have long been a Philadelphia landmark along the Delaware River — originally a statement of power and progress, then a resilient monument to urban decay, burned-out candles on a concrete cake. Now they’re painted up real nice so renters can live amid them.

“They look pret-ty great,” says Kevin Kozlik, director of field operations for the power plant’s redevelopment, as we stand on the roof admiring the workmanship. They’re painted pale gray, not too dark, because there might be plans to dramatically light them at night, but not white, because “we didn’t want it to look like a cruise ship.”

“We had to bring in people who paint bridges,” says Leonard Klehr, who’s with project financier Lubert-Adler. “They were hanging from … ”

- Philly’s Rapid Redevelopment Is Putting Its Architectural Character at Risk

- We Built This City: The Know-It-All Guide to Philadelphia Architecture

“Air-hoist cables,” Kozlik helps.

The power station opened in 1923, maybe two miles from where Ben Franklin first tried downloading electricity for Philadelphia. It soon became the biggest generator of juice for a booming city. In the 1920s, America went from most people not having electricity at home to most people having it. Buildings like this transformed the world. As it turns out, coal-burning over the past century is believed to have been the biggest human contribution to climate change, which, worst-case, could wipe out humanity. A hefty share of that carbon emission came from right here in Fishtown, from this magnificent Beaux Arts building designed by John T. Windrim, the same architect who did the Franklin Institute.

Electricity eventually became a little cleaner, and cheaper to get in other ways. But it took decades of deterioration and graffiti, and the filming of steampunk Bruce Willis scenes for the 12 Monkeys movie, for anybody to figure out what to do with this 223,000-square-foot building. Now, as soon as this summer, it will become luxury apartments with eye-popping city views, co-working and cafe space (smoke-free!), and wedding ballrooms, with picturesque Penn Treaty Park next door and new public access to the riverfront that could eventually include a floating concert barge . So let’s live it up while we can.

The development, christened the Battery , is part of a waterfront revival that over the past decade has reconnected residents to the city’s two rivers, with attractions like Spruce Street Harbor Park, Cherry Street Pier and Schuylkill Banks Boardwalk. It’s also the latest relic of Philly’s more formidable days to get an expensive makeover (projected at $153.6 million) and a new life in a new century.

Courtesy of NQS Creative

These days, our culture sometimes seems split between folks eager to obliterate the past in favor of progress and others who imagine making things “great again” by turning the clock backward and retreating to yesterday. Restoration projects like this — and the Divine Lorraine Hotel and Metropolitan Opera House on North Broad Street, South Philly’s Bok Building, the Navy Yard — may imperfectly symbolize a middle ground. They’re ways to revive pieces of the past as part of moving forward. The old days weren’t all roses and chardonnay. There’s plenty we’ve needed to demolish. Coal-burning electric plants, your dirty days are numbered. But these sturdy, pretty buildings still have possibilities.

Leonard Klehr meets me in the parking lot alongside the power plant for my walk-through of the construction. For a while, there was a smaller, secondary generation plant on this lot, but it was ugly and was razed in 2008. Fancy extra buildings may eventually replace these parking spaces if the market stays hot.

Klehr, a Philadelphia attorney, first introduced two of his clients, Ira Lubert and Dean Adler, to each other in 1997. They started Lubert-Adler to manage real estate investment funds, buying, fixing, operating and selling properties for investors. Projects that qualify as historic buildings, like this PECO plant, get a federal tax credit of 20 percent of money spent on restoration — a nice return for Lubert-Adler’s investors even before the building opens for business. Renovated properties also qualify for a 10-year city tax abatement. (This year, the abatement for brand-new construction falls from 10 to five years, potentially incentivizing more adaptive reuses like this.)

In 2006, Klehr resigned from his own law firm to join Lubert-Adler. Now he’s executive vice chairman — and unofficial tour guide. Standing in the parking lot, he waves a hand along the north side of the building.

“This will all be opened up. We’re bringing Palmer Street straight down to the river,” he says.

Rendering courtesy of NQS Creative

Well, kind of. This side of the building, historically gated off, will become a public segment of Palmer Street, a landscaped promenade where pedestrians and cyclists can frolic together. Like much of the waterfront, it will still be cut off from the city by Delaware Avenue and I-95. “But there’s been a lot of talk about opening up those streets to allow flow back and forth to the riverfront,” Klehr says hopefully.

We stroll to the city-facing west side of the building. Along Beach Street, there’s a spiky wrought-iron fence to keep people out. “For many years, there was barbed wire on top of it,” Klehr says. “This was a dangerous building, a coal-fired power plant. For 100 years until now, these 11 acres were sealed off.”

We meet up with Kozlik, from general contractor Fastrack Construction, and head to the waterfront side of the building. Jutting into the river here is Pier 61, the coal pier. Barges from Petty’s Island, the company’s primary coal yard, on the Jersey side of the river, would dock here.

“They would clamshell the coal with a crane, put it into a hopper, and it would go into a crusher that would make it the right diameter,” Kozlik explains. Now, the developers might connect the coal pier with a 195-foot floating bandstand designed by Louis I. Kahn, itself a clamshell, that Lubert-Adler bought and needs a place to park.

In the old days, a conveyor belt moved the pulverized coal from the pier to the first section of the plant, the Boiler House, where three-story-high bins dumped it into roaring furnaces that boiled river water into steam. The steam was piped to the middle part of the building, massive Turbine Hall, where it spun rotors inside six long turbines that looked like Harkonnen spaceships from Dune , to create electrical current. The current then passed to the third section, the Switch House along Beach Street, where transformer units resembling long aisles of metal lockers streamed electrons into the city’s wires. The entire building was filled with industrial-era pipes, valves, switches, platforms and gangways, but it also had arched doorways and vaulted ceilings with skylights.

Philadelphia Electric Company built three of these monumental stations along the Delaware. The first and most ornate was down in Chester. It’s beautifully redone as offices now — owned, inhabited and leased by the Philadelphia Union soccer team. This Delaware Generating Station came next. The Richmond station, farther upriver, remains an urban wreck between a city sanitation center and the Betsy Ross Bridge.

In a 2008 exhibition at Philadelphia’s Athenaeum and a 2016 book , photographer Joseph E.B. Elliott and University of Pennsylvania historic preservation and landscape architecture professor Aaron Wunsch called these buildings “Palazzos of Power.” Elliott had won a grant to take pictures inside the buildings, and he told me he encountered the Delaware station “as this kind of lost ruin, like a sort of pyramid in the jungle.”

In fact, the power plants were meant to seem ancient when they were new. The neoclassical Beaux Arts style borrows from Roman, Greek and Renaissance architecture. It’s known for grand scale and flourishes we don’t talk about much anymore, like cornices, quoins and dentils. At a time when the whole idea of an electric company was novel and there was a debate over whether this vital utility should be run privately or by the government, Philadelphia Electric Company used its majestic buildings to pass itself off as a civic institution. These buildings were purposely built to inspire awe from afar, implying both tradition and progress.

“Why the hell does this power plant in this industrial neighborhood look like a Roman bath?” Wunsch asks. “All these big companies wanted to project the image of permanence — that these are institutions you should trust and want to invest in because they are so damn substantial. That tends to play out in classical terms. I consider them artifacts of public relations, actually. You can go back and forth on whether they’re great architecture. But they were meant to have a kind of civic presence, and lo and behold, they kind of do.”

We enter the building, which has been mostly gutted, and head for the money shot, the vast Turbine Hall, its skylights 90 feet above the floor. This is a large room.

“It makes 30th Street Station look puny,” Robert Powers, whose firm wrote the nomination that got the building on the National Register of Historic Places, warned me. Lubert-Adler hasn’t figured out what to do with it yet and is waiting for COVID’s dust to settle to see what people still want to congregate for. “Office space, event space. We think it’ll be market-driven, as opposed to somebody’s dream or vision,” Klehr says. It’s not unusual for adaptive reuse projects with oddball spaces to evolve in phases.

Developers reimagining turbine halls elsewhere have tried various ideas. In 2000, London’s former Bankside Power Station became the Tate Modern, a gorgeous art museum on the Thames River. Its cavernous turbine hall is for extra-gigantic sculptures. Baltimore’s former Pratt Street Power Plant briefly became an indoor Six Flags amusement park. (Now, it’s a mall.) In Chester, they built a partial mezzanine within the turbine hall, creating a sort of upstairs platform. A software company had offices there but is gone now. It looks like a desolate Grand Central Station inside.

One encouraging sign for our long-term comfort on the planet is just how many of these coal-burning plants are becoming something else. Their closures reflect an evolution in how we extract megawatts from nature, and their reopenings reveal what we want city buildings to do today. The old L Street Power Plant in South Boston is becoming an office/retail complex. The Greenidge power plant in upstate New York now does Bitcoin mining. Even London’s iconic Battersea Power Station , the one on the cover of the 1977 Pink Floyd album Animals with the helium-filled pig, is being prepped for reopening this year as a high-end residential and retail megaplex. Its control room will be a ritzy bar; residents will include Sting, and Apple will have its U.K. campus there, with iPhone-shaped elevators. London has given the building its own tube station. But alas, no dice getting a SEPTA train stop at the restored PECO plant. Klehr says a private shuttle is under discussion.

My guides and I head to the Switch House, the section of the Battery closest to city streets. A long room that once contained transformers will be skylit space for weddings, operated by Joe Volpe’s Cescaphe Event Group .

“All of our venues have been something else in the past,” Volpe tells me later. “Cescaphe Ballroom was an old movie theater. Vie on Broad Street was a car dealer. Tendenza was a brewery. So here was this mysterious, giant building. I fell in love with the scale of it.”

Volpe isn’t merely operating the weddings concession; for a while, he owned the building. He and developer Bart Blatstein bought it from Exelon in 2015 , for a reported $3 million. They planned to make it into an event space with restaurants, a banquet hall and guest rooms. Blatstein soon sold his share to Volpe. The big plan didn’t materialize.

“As I started to dig in, I realized it was just out of my league. It was just bigger than me,” Volpe says. He was able to unload the place to Lubert-Adler in 2019 while remaining an investor. The wedding venue will open in the fall, with its own elegant name, to be determined. “Definitely not the Battery,” Volpe says.

There was a time when the transformers here were Philly’s prime electricity source. These days, we’re on a 13-state network called the PJM Interconnection. Our mix of fuel is the same as everybody else’s on this regional grid: at press time, roughly 38 percent natural gas, 33 percent nuclear, 22 percent coal, and six percent renewables.

As part of our planet’s desperate attempt to survive, the City of Philadelphia wants to be carbon-neutral by 2050 and released a Climate Action Playbook in 2021. There will be obstacles. One challenge is that the city owns Philadelphia Gas Works, so it’s launched a study to explore how to achieve carbon neutrality with America’s largest municipally owned natural gas utility. When I speak about this with Christine Knapp, director of the city’s Office of Sustainability, I suggest it’s as if the Eagles decided to become a baseball team but had to keep a lot of the football players.

“Yeah, but then imagine the stadium has to be converted and all the infrastructure has to change, too,” she says.

But electricity is bigger than ever. In the recent book Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future , author Saul Griffith suggests we electrify everything, including heating and vehicles, and move toward 100 percent renewable sources. His energy future involves a lot of high-capacity batteries.

Will this transformed electric plant have batteries? It’s literally called the Battery. I knew the name wasn’t meant to honor Philly sport fans chucking D-cells at J.D. Drew. Historically, buildings called “batteries” along the Delaware River had guns aimed at the British.

“We think it connotes ‘new energy,’” Klehr emails me. “Our premise is that in an ESG world, the preservation of an old building like the Battery is the starting point for sustainability.” I had to google ESG. It stands for “environmental, social and governance” — corporate-citizenship factors that guide some investors. Adaptive reuse for sure is more eco-friendly than raze-and-rebuild, but the Battery isn’t doing anything especially green for its energy. There won’t be solar panels or offshore windmills. “There are no plans to push the envelope. It’s gonna be energy-efficient,” Klehr says.

Finally, our tour hits the Boiler House section on the river, where the deluxe apartments will be. It’s all rentals. The first two floors will accommodate commercial spaces as well as a central area called the Hub, essentially a co-working space. Floors three through eight will be strictly residential. “They’ll have an apartment, and then they’ll have a little space here where they can work on their craft,” Kozlik says.

We climb temporary staircases to higher floors — six stories in the building plus two newly added atop the roof. “We keep going up and it only gets better,” Kozlik says. It really is a million-dollar view from this location, a panorama of the Ben Franklin Bridge spanning the river, then the entire city skyline. The south side overlooks one of the city’s prettiest parks, the legendary spot where William Penn officially grabbed all this land from the Lenape in 1683. As we approach the location of the swanky corner penthouse, Kozlik jokes: “Eleven hundred a month!”

Ha, not likely. Prices aren’t set, but this isn’t an “affordable housing” development. In some ways, the ritzy building will remain as locked away from uninvited guests as when it was swathed in barbed wire. This is land-use change, not social change. But it’s a kind of progress, re-beautifying the sort of post-industrial eyesore the mayor of Detroit recently called “ruin porn.”

“There’s no playbook for this,” Klehr says. “We’ve done adaptive reuse projects — office to apartments, warehouse to apartments, warehouse to office. But this place didn’t have any real estate purpose. This was a machine that they built this beautiful Beaux Arts envelope around.”

“We had to find a purpose for it,” Kozlik says. Of course, in a residential market as hot as today’s, anything can have real estate purpose. Up on top, just outside one of the rooftop apartments, Kozlik points to a doorway-shaped cutout in one of the smokestacks. A floor has been installed in the stack so you can stand inside and see the sky. It’s not a big enough space for somebody to live in, but a renter could go in there to have a beer or grill a burger. Hey, when you want to reuse things that have lost their use, you need to get creative.

“This unit is going to have a walkout patio that’s inside the smokestack,” says Kozlik. “How cool is that?”

- architecture

- Delaware River Waterfront

Where to Live in the Philadelphia Region if You Love the Arts

Where to Live in the Philadelphia Region if You Love Nature

Living in Northern Liberties: A Neighborhood Guide

Living in Chadds Ford: A Neighborhood Guide

$1.4 million philly real estate showdown: wayne vs. fishtown, the bellevue makeover preview: version 4.0 nears the finish line, 5 must-see open houses this weekend, in this section.

support our work

.logo-hidden { fill: #2a625b; } .logo-city { fill: #231f20; }

exploring philadelphia's urban landscape

Behind the Gates of Delaware Generating Station

Photo: Chandra Lampreich

Editor’s note: On November 3, bids for the former Philadelphia Electric Company’s Delaware Generating Station will officially close and a new owner of the massive Fishtown power plant will be revealed. Towering above Penn Treaty Park, the 223,000 square foot plant, almost a thousand feet of waterfront, and the 16.4 acres it resides on has a staggering—if not down right intimidating—amount of potential. One of four power plants along the Delaware designed by John T. Windram, of The Franklin Institute and Family Court fame, it has a distinctive beauty that could shine again if chosen for a creative renovation (The former Bankside Power Station in London that now houses Tate Modern comes to mind). Demolishing the 97 year old generating station would be unfortunate and shortsighted, but the renovation and reuse of the building may be prohibitive. Current owners, Exelon Generation Co. LLC, and the real estate brokers of the property, Biswanger, haven’t made an estimate of the price tag public so we’ll have to wait until the winning bid is announced. Built on the former site of the Neafie & Levy Shipyard —birthplace of the Navy’s first submarine and destroyer and America’s first steam powered fire engine—the station has a century’s worth of industrial infrastructure lurking underneath it and will have to be addressed even after site assessment and a first pass at environmental remediation. Needless to say, what the new owners do with the plant and its parcel will be transformative and likely to push development along the abandoned northern sector of the Delaware waterfront as it moves past the Sugarhouse Casino toward Port Richmond.

Photographer Chandra Lampreich affords us a peek inside the Delaware Generating Station as it stands today.

Tags: Delaware Generating Station Fishtown Penn Treay Park Philadelphia Electric Company

About the Author

Chandra Lampreich Chandra Lampreich became interested in photography in high school, and then continued her training at Antonelli Institute where she received an associates degree in photography. She specializes in architecture photography, and has a passion for shooting old, dilapidated buildings. Her photographs can be seen on Flickr here .

9 Comments:

Awesome pics!!!

How did you get in??…I work at the building next door and have been wanting to get in here. Did you ask anyone or just walk in??

Chandra, you really captured the massiveness of that plant. I’ve passed it a million times, always wondering what the interior must look like.

Those pictures are fantastic Chandra, thank you. Also saw your pictures of my old church St. Bonaventure’s while they were tearing it down. It will be quite an undertaking tearing that massive structure down.

Now this building would make a great hidden city tour!

I have photos of the switch house, the boiler sections, construction photos, hidden areas, and even the demolished section including a time when some areas still had electricity and lights on.

Hello! My name is John Kramer. I am creating a documentary of the history of my favorite buildings, the Philadelphia generating stations. I would love to get in touch with you to see the photos you have taken of the demolished section that the retired workers refer to as “the new plant”. You can reach me at [email protected] or my phone number 2674552031. I hope to hear from you!

Seems like there is hardly any graff in these flicks. Must be old ones.The stacks all have writing on them now and one even has a american flag on it. The flag showed up 4th of July 😉

Oh what I wouldn’t give to get in there my camera — gorgeous pics!

speechless!. Simply amazing what at one time was built on this site. So much history yet so few care about the greatness of our city

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Power Plant Productions

230 N 2nd Street Philadelphia, PA 19106

215.592.8775

Get Directions

Closest parking facility, old city parkominium.

Located directly across the street from Power Plant, Old City Parkominium offers our clientele a preferred discount.

Managed by Park America 231 N 2nd Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 238-1334

Other nearby parking facilities

Holiday inn at penns landing.

100 N Christopher Columbus Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 568-4025

304 Race St Garage (Safeparc)

304 Race St, Philadelphia, PA 19106 (267) 519-9420

210 Filber St Parking (near the Arden Theater)

210 Filbert St Philadelphia, PA 19107, US (215) 629-9652

Factory Tours

Get a good look at american manufacturing.

Factories are one of the many reminders of our state’s prized industrial heritage. From coins and motorcycles to potato chips and chocolate, many Pennsylvania factories offer tours and are the perfect places to find Made-in-PA keepsakes.

Get trip ideas

City Life The Great American Getaway Guide to Pittsburgh Long known as the Steel City, Pittsburgh has transformed itself into a modern, bustling metropolis where arts and culture thrive, historic buildings have been reimagined into trendsetting restaurants, ... Read More

City Life Best Things to Do in the Pocono Mountains What do scenic hiking trails, thrilling waterparks, and premier casinos have in common? You can find them all in the Pocono Mountains! If you're traveling to northeast Pennsylvania and want to know wh ... Read More

City Life Best Things to Do in Philadelphia Planning a visit to Pennsylvania's largest city? If you're wondering what to do in Philadelphia, your options are truly endless! Explore America's constitutional history, reenact an iconic movie scene ... Read More

Factory Tour Destinations

Results are limited to a 25-mile radius

Hanover, PA Snyder's Of Hanover Factory Outlet

Columbia, PA Turkey Hill Experience

Hanover, PA Utz Quality Foods

Souderton, PA Asher's Chocolates Factory

York, PA Wolfgang Confectioners

Easton, PA Crayola Experience

Lewistown, PA Asher's Chocolates Factory - Lewistown

Philadelphia, PA U.S. Mint

Saint Marys, PA Straub Brewery

Brookville, PA BWP Bats, LLC

Hershey, PA Hershey

Lakeville, PA Sculpted Ice Works Factory Tour & Natural Ice Harvest Museum

Mount Joy, PA Wilton Armtale Factory Store

Hershey, PA Hershey's Chocolate World

Lititz, PA The Julius Sturgis Pretzel Bakery

Hershey, PA Hersheypark

Cresco, PA Callie's Pretzel Factory

Mountainhome, PA Callie's Candy Kitchen

Tyrone, PA Gardner's Candy Museum

Mercer, PA Wendell August Forge

York, PA Harley-Davidson Vehicle Operations Factory Tour

Nazareth, PA C.F. Martin & Co.

Scranton, PA Lackawanna Coal Mine Tour

Geigertown, PA Joanna Furnace Historic Site

Altoona, PA Benzel's Pretzel Bakery

Nottingham, PA Herr's Snack Factory Tour

Pottsville, PA Yuengling Museum & Gift Shop

Thomasville, PA Martin's Potato Chips Inc.

Lebanon, PA Weavers-Kutztown Bologna Inc

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use our website, we will assume that you are happy to receive all cookies (and milk!) from visitPA.com. Learn more about cookie data in our Privacy Policy

- Explore the Trail Trail Map Activity Guides FAQs

- Events All Upcoming Community Events Kayak Tours Movie Nights Riverboat Tours Host Your Event

- Get Involved Donate Volunteer Sponsorships Merchandise Subscribe Our Supporters

- About SRDC History Board Partners Plans & Reports Contact

Generating Energy on the Lower Schuylkill

The Schuylkill Station continued to evolve throughout the 20th and 21st Centuries. Co-generation of steam and electricity for heating systems around the city began in 1950. In 2013, Veolia North America completed a $60 million project that converted the power plant from fuel oil to natural gas, reducing its emissions. The power plant’s new owner, Vicinity Energy of Antin Infrastructure Partners (AIP) of Paris, France, continues to invest in the power plant, making it more efficient and environmentally sustainable using its green steam technology. According to a Philadelphia Inquirer article , this green steam is delivered to "162 customers through underground pipes beneath city streets and sidewalks. It is one of the city’s biggest energy distribution systems, and its customers include office and residential towers, hospitals, and city government buildings, including the Parkway Central Library and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The University of Pennsylvania consumes much of its output.”

Head over to the southern end of the South to Christian trail segment to see this century-old energy generating complex.

The story of a forgotten America.

- Royalty-Free Images

Delaware Station of the Philadelphia Electric Company

The Delaware Station of the Philadelphia Electric Company is a closed 468 MW coal-fired power plant along the Delaware River in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The earliest electric supply companies that emerged in the late 1800s supplied power for a particular product or building. At the outset in Philadelphia was the Brush Electric Light Company in 1881 to install and provide power for new electric street lamps along Chestnut Street. 1 Another, the Edison Electric Light Company, replaced gas lighting in homes and businesses with Edison’s patented incandescent bulbs. Before long, dozens of such utilities had emerged to generate electricity for a wide variety of uses.

The Philadelphia Electric Company (PEC) was founded in 1881 9 and incorporated in 1902 in part to consolidate the growing number of electric companies, create a standardized electrical grid, and switch from direct current to alternating current to boost the transmission range. 1 It desired the erection of a large centralized plant that could provide all of the electricity that the city needed at a lower cost than the many smaller, less efficient plants. The PEC acquired a tract of land on Christian Street at the Schuylkill River around the turn of the century and began construction on Schuylkill Power Station in 1902, the largest coal-fueled power plant in the world at 81 MW. But an electrification project along the Pennsylvania Railroad and rapid growth in industrial customers enabled the construction of an addition to Schuylkill to bump up its capacity to 130 MW.

Chemical, shipbuilding, and steel factories began to emerge along the Delaware River south of Philadelphia in the 1910s. 1 After electricity shortages were reported, planning efforts began on PEC Chester Waterside Station, a new 120 MW power plant at the cost of $5.5 million, which was put into full operation in 1919.

Delaware Power Station

In 1913, 1 Joseph B. McCall, board chairman of PEC, purchased 8½ acres of the former Neafie & Levy Shipyard in Kensington for the site of a future power plant as it had over 400 feet of frontage along the Delaware River, close to PEC’s primary coal yard on Petty’s Island, and was close to numerous industrial sites. 6 9 (The shipyard was where, in November 1861, the Union government placed an order for the construction of an iron submarine. 5 Christened the Alligator, it was the first submarine of the Civil War, rushed into service with the purpose of destroying the Confederate ironclad, Merrimack.)

But after the United States entered into the Great War in 1917, the city of Philadelphia blossomed under strong industrial growth, particularly in the shipbuilding, locomotive production, ammunition, and textile industries, threatening to overwhelm the PEC and cause systemwide power shortages. 1 It was decided to construct the Delaware Power Station in Kensington on its previously acquired site.

John T. Windrim, who had also designed the Schuylkill and Chester power plants, was hired to design the new facility. 1 9 Architecturally, Windrim sought to use the Beaux-Arts style to create a monument to electricity and impart a sense of stability and permanence. Windrim was paired with William C.L. Eglin, who had introduced revolutionary engineering technologies in power plants. 9 Stone & Webster, a national engineering and construction firm, was hired as the general contractor.

Initially, the complex was to be erected with steel, but a shortage of materials because of wartime manufacturing led to the use of reinforced concrete, a far heavier material. 1 It required anchoring the power plant down to bedrock at a much higher cost.

Although construction for the foundations of the new Delaware Power Station began on September 25, 1917, work stopped due to a lack of funds in December. 1 9 The PEC was struggling to find the money to complete the Chester Power Station and pay off a $2.5 million loan to the Drexel & Company. Additionally, the cost of Delaware, at $24.5 million, was far above any other power plant at the time. Finding investors during wartime was challenging, and the federal government declined to provide any financial assistance to the PEC for the station’s construction even though the plant’s ill-completion could result in power shortages to shipyards and other industries vital to the war effort.

Despite a drop in electricity use from some industrial sites after the Great War concluded in November 1918, the “domestic revolution” swiftly overtook demand thanks in part to PEC’s “Wire Your House” campaign. 1 By the end of the year, the PEC had 103,015 customers, a nearly fivefold increase from 1907.

Finding investors was an easier sell in peacetime, and through the sale of stocks and bonds, the PEC was able to raise large sums of financing to fund half of the new Delaware Power Station. Construction resumed on the plant on September 28, 1919, 9 and the first 30 MW turbine of the six planned was put in operation on October 30, 1920. 8 9 The second 30 MW unit came online by the end of the year. 1 6 Even so, Delaware, at one-third of its planned capacity, was able to provide 25% of Philadelphia’s total peak load of 240 MW for 1921. 1 A third 30 MW turbine came online in January 1922 as peak demand had approached supply.

Work to construct the second half of Delaware began in December after a successful sale of stocks and bonds. 1 The fourth and fifth 30 MW turbines were installed in 1923, followed by the final 33 MW turbine in 1924. All six turbines, producing 183 MW, 9 burned 325 tons of coal per hour. 5

Shortly after the Delaware Power Station came online, the PEC planned for an even larger power plant to keep up with demand. The proposed Richmond Power Station would feature 12 turbines and a total capacity of 600 MW, but by the end of 1925, when the first of the three planned turbine halls had been completed, and two of the twelve 50 MW generators installed, electricity demand had begun to level off. 1 Although two additional turbines were installed at Richmond in 1935 and 1952, the full plan was never realized and Delaware remained the largest in both footprint and generating capacity for the PEC.

Between 1926 and 1930, the PEC merged with the Pennsylvania Power & Light Company and New Jersey’s Public Service Electric & Gas Company to form the largest power grid in the nation. 9

Electricity usage began to surge again with a post-World War II housing boom taking shape around Philadelphia, and new capacity was required. The PEC acquired the former William Cramp & Sons Shipyard 1 just north of the Delaware Power Station, hired David Marano as the architect for a contemporary expansion of the power plant, 9 and spent $41 million to construct two 136 MW generators in a separate turbine hall. 1 The new units more than doubled Delaware’s capacity when they began operating in 1953; as several of the original turbines had been replaced, the Delaware Power Station was capable of handling nearly 468 MW.

The new addition debuted new television camera equipment that monitored water-level gauges of the boilers and transmitted the picture to a control room. 7 Specially designed cameras also peered into the furnaces to watch the boilers’ 16 firing points.

The boilers, designed to run on both coal and fuel oil, were converted to run on fuel oil only in 1972. 9

In the 1950s, three generators in Boiler House No. 2 were converted to run on more efficient fuel oil rather than coal. 1 In 1969, all six of the original turbines were put into standby status, operated only as needed for periods of increased demand and load balancing, and in 1972, the circa 1953 units were converted to run on fuel oil. 9 Eventually, the original turbines were retired in 1984. 5 After PEC was acquired by Exelon in 2000, 9 the remaining two 47-year-old turbine units were placed into standby status until 2004 when they were retired. 9

Redevelopment

The circa 1953 addition, along with the oil tanks, were abated and demolished beginning in August 2009. 5 Exelon then tapped Binswanger real estate brokerage to sell the Delaware Power Station, excluding a one-acre gas turbine plant, in the fall of 2014. 4

In August 2015, developer Bart Blatstein and business partner Joseph Volpe, of the Cescaphe Event Group, acquired the former Delaware Power Station site for $3 million. 2 3 The pair has proposed converting the derelict power plant into two hotels, two event spaces, and restaurants. 2 Refined plans in December showed two event spaces for private weddings and corporate gatherings, two restaurants open to the public, and blocks of reservable rooms for events, dropping the hotel rooms from the project. 3

The Boiler Houses, Storage Area, Turbine Hall, and Switch House represented component functions in the electrical generation process. 1

Boiler House No. 1 and No. 2, separated by a five-story central coal storage area, were built of reinforced concrete with “THE PHILADELPHIA ELECTRIC COMPANY” and “DELAWARE STATION” inscribed in teal-colored ceramic tiles on the exterior. 1 The roof contains eight cylindrical metal steam stacks. To the west of the Boiler Houses was the Turbine Hall, the main operating space where turbines, powered by steam created in the boiler houses, generated electricity. 1 The Turbine Hall was lit with six gabled skylights. The Switch House, fronting North Beach Street, contained electrical substation equipment for the Philadelphia Electric Company.

To the rear of the power plant was Pier 61, which measured 75-feet wide and extended for about 250-feet into the Delaware River. 1 Located near the east end of Pier 61 was the Coal Tower, a five-story reinforced concrete building used to lift coal delivered from barges on the river. An Ash Tank was located along the bulkhead just east of Boiler House No. 1, adjacent to the Screen House and Pump Room.

Coal, which arrived on barges from Petty’s Island, would be lifted by boom hoists and dropped into the coal tower, where it was broken down and crushed for the original turbines. 1 After processing, the coal would be transported on a conveyor to a tower above the storage area between the two boiler houses. Cross conveyors, which extended from both sides of the tower, delivered the coal to the boiler houses into four bunkers, each of which contained three compartments supplying two boilers each. Once fed, the boilers would heat feed water to generate steam, which would then be piped under pressure to the turbines. The turbines would spin the adjacent generators to create electricity, which would then be distributed out through the switch house.

The process was similar for the circa 1953 units, except that the coal was pulverized finer than talcum powder before being blown into the furnace, requiring only less than a tenth of the amount of coal required from older operations to produce a kilowatt-hour. 7

Simultaneously, cooling water would be continuously piped in from the river and filtered through the pump house and screen room, then supplied to the condenser units below each turbine. 1 Within the condensers, the steam would be cooled into condensate, which would then be recycled and used again as feed water. The excess would be released back into the river.

- United States, Congress, National Park Service, and Kevin McMahon. “The Delaware Station of the Philadelphia Electric Company.” 2015.

- DiStefano, Joseph N. “$3 million for Peco’s ex-Delaware Station.” Inquirer [Philadelphia], 13 Aug. 2015.

- Brey, Jared. “Developers seek community support for Delaware power station overhaul.” Plan Philly , 16 Dec. 2015.

- DiStefano, Joseph N. “Exelon plans Nov. sale for Fishtown ex-power station on the Delaware.” Inquirer [Philadelphia], 10 Sept. 2014.

- Ujifusa, Steven B. “Demolition at Delaware Power Plant.” Plan Philly , 21 Aug. 2009.

- Wainwright, Nicholas B. History of the Philadelphia Electric Company 1881-1961 . 1961.

- Segal, Abraham. “Delaware Powerhouse.” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine , 15 Nov. 1953, pp. 30-31.

- “Starts New Generator.” Philadelphia Inquirer , 31 Oct. 1920, p. 2.

- Philadelphia Historical Commission. “Philadelphia Electric Company Delaware Generating Station.” 2016.

[…] More About This Location […]

This site appears to be closed for redevelopment. There are now round-the-clock private security stationed and most days there are work crews inside the site.

This October 30 is the 100 the year anniversary of the PEC. When built it was the largest in the country and remained so. In today’s money the 25 million then to build it in 1920 is equal to a 500 million today or half a billion. Everyone is happy this national treasure has been saved. There should be a ceremony by city, state and country marking the anniversary.

Leave your comment! Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Related Posts

Autumn Flyover of Abandoned Tater Knob Lookout Tower

Tater Knob Lookout Tower is an abandoned fire lookout tower in Bath County, Kentucky.

Parker Tobacco Demolition

It is with some sadness that the Parker Tobacco Company is being demolished.

The Lost Tunnels of the Norfolk & Western Railway in Wayne County, West Virginia

In Wayne County, West Virginia, particularly in its rural areas, lie the abandoned tunnels of the former Kenova District, Scioto Division of the Norfolk & Western Railway.

The Ghost Town of Nuttallburg, West Virginia

Nestled along the winding New River in Fayette County, West Virginia, lies Nuttallburg, a town forged from the ambitions of English entrepreneur John Nuttall. With foresight and determination, Nuttall acquired land rich in coal seams, anticipating the arrival of the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway in the early 1870s.

Site search

- Los Angeles

- San Francisco

- Historic Homes

- Home Ownership

- Renting a Home

- Homes for Sale

- Tiny Living

- Home Tech Tips

- Interior Design

Filed under:

- Photography

- Historic Preservation

Philadelphia’s abandoned power plants look like steampunk temples

New photobook Palazzos of Power explores the neoclassical grandeur of these artifacts of the early electric age

Monumental structures that tower over the industrial landscape in Philadelphia, the aging central power stations of the Philadelphia Electric Company look like Metropolis meets Ancient Greece, ornate temples of stacked brick, soaring arches, and early industrial grit. But these hulking structures hide a more interesting backstory about how design can be enlisted to shape public perception.

“I looked at these buildings and thought, on the surface, they’re incredible structures, enormous and beautifully designed,” says Aaron Wunsch, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s graduate program in historic preservation. “They were designed to look like public monuments, which was strange. There’s a weird juxtaposition of civic building and factory floor.”

In Palazzos of Power , a forthcoming book about the history of these structures featuring striking black-and-white photos of Joseph Elliot, Wunsch breaks down the history of these early 20th century generators, surprisingly well-designed industrial landmarks that say a lot about how architecture can be both an aesthetic asset and public relations.

Mostly built between 1903 and the tail end of WWI, these stations were the work of engineer William C.L. Eglin and architect John T. Windrim, who took Beaux Arts as a primary influence when drafting these coal-powered temples to modernity. While Wunsch says none of the stations were necessarily groundbreaking designs, they did recall many of the best aspects of neoclassical style. Richmond Station reminds him of the long-lost Penn Station.

“Windrim is an expert in functional design, which leads to a sort of ‘stage-set classicism.’” says Wunsch. “It’s not radical innovation. But what makes it exciting is that this style is getting applied to buildings without a classical precedent.”

Windrim’s designs reflected the messaging of the Philadelphia Power Company (PECO), which, in the early Progressive Era, was viewed warily by a citizenry suspect of trusts, monopolies, and the industrialists that controlled a key utility of modern life. Located in an inner industrial belt of the city, outside of downtown, the buildings were nonetheless large billboards for PECO, meant to communicate to anyone living in Philadelphia that this company was an upstanding company serving the public good.

“These buildings had to pitch themselves to people,” says Wunsch. “The sublime classicism of these structures, all owned by a powerful private company, are meant to convince others that they’re in some sense public buildings.’”

A few decades after construction, these plants were converted to burn oil, which, along with a move to turn many into substations, extended their useful lifespan. By the ‘90s, all of them had ceased operation, which was why it was so exciting for Wunsch to discover them while working on the Historic American Building Survey in the late ‘90s. Many still had remnants of a time when they were still generating power, including old time cards scattered across the floors.

As the Philadelphia has expanded, many of these plants, once on the city’s edge, are now potential targets for redevelopment. Delaware Station was recently purchased by a developer looking to build an events space. While the retro flourishes and imposing design offers numerous chances for renovation or rebirth, Wunsch hopes readers of the book can appreciate the scale and story behind these early 20th century relics.

“These plants formed the network for modern life,” he says. “Like the server farms of today, they’re incredible modern utilities.”

Next Up In Photography

- Retro malls live forever in rad new photo book

- 25 dreamy A-frame cabins we love

- Feast your eyes on Gaudí’s whimsical stunner, El Capricho

- Are these the best architectural photos of 2018?

- 14 Instagram accounts that show our national parks in all their glory

- See brutalist buildings in the moment of destruction

Share this story

A news magazine about the Delaware River and the people who use it.

Power plants on the Delaware: Abandoned but still celebrated

By Chris Mele | November 22, 2021 For Delaware Currents

Behemoth buildings that once housed power plants and supplied electricity to Philadelphia dot the Delaware — remains from more than a century ago — that remind us of the history and development of the region.

Many of these former generating stations, some of which were built in the early 1900s and the 1910s by the Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO), have fallen into disrepair, left subjected to the elements and preyed upon by vandals and scrap metal thieves.

With their rusting hulks of turbines, pipes and valves and defunct control rooms with dials and buttons, the vibe of these places is that of a decaying, demented Willy Wonka Chocolate Factory (minus the sweet treats and Oompa Loompas).

The control panels at the former Southwark Generating Station. The plant was built in the 1940s and was considered emblematic of post-war optimism. PHOTO CREDIT: The Proper People

Nonetheless, these abandoned properties are alluring to historic preservationists and urban explorers alike.

What’s the attraction?

“It’s the closest thing we have to Roman ruins,” said Aaron Wunsch , an associate professor in the graduate program in Historic Preservation and in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

“First of all, they’re mysterious,” he added. “Second, they’re massive, and we just don’t have anything like them anymore.”

Buildings stood for “solidity and immensity”

What makes the former power plants on the Delaware unique is that they were built on or near a major city (in this case, Philadelphia) and during the Roaring Twenties, when companies were willing to invest in edifices that made a statement, said Michael Berindei, an urban explorer who has visited the sites.

The 1920s were a peak period of ornate buildings that signaled they’d be there forever as opposed to today when power plants are essentially warehouses of generators, he said.

Back then, they were considered art.

Electricity at the time was still new and some members of the public needed to be reassured it was safe. The buildings had a way of projecting that sense of confidence, he said.

To comprehend the sheer mass and scale of these plants, consider that one of these plants, the Southwark Generating Station, viewed through Google 3D, would take up two blocks in Philadelphia and would be half as tall as some of the city’s skyscrapers – even taller if you consider the smokestacks, Berindei said.

He said some of the plants are so mammoth that parts of them can actually have their own climates. It’s not unusual, for instance, to see clouds or haze forming in one section of the building versus another.

The future of the former Southwark Generating Station in Philadelphia is unclear. Vandals and scrap metal scavengers have gutted much of the interior. PHOTO CREDIT: The Proper People

Wunsch, who co-wrote the book “Palazzos of Power,” about Philadelphia power generating stations built by PECO from 1900 to 1930, started to explore the former plants as part of a master’s thesis in the 1990s.

He was drawn to them in part because, as he put it: “These are totally over the top. What’s going on here?”

The answer to that, in a historical context, is that the buildings were part of political and public relations campaigns waged by the power company.

At the time that some of these coal-fired plants were built, PECO was trying to beat back criticism that it had underfunded its infrastructure and was overcharging its ratepayers.

It was also at a time when there was a tug of war over whether utilities such as PECO should be privately or publicly controlled, Wunsch said.

The buildings stood for strength and permanence , a signal to its customers and regulators that the power company was reliable and dependable. PECO so embraced this concept that in the captions of its drawings for the plants were the words “solidity and immensity,” Wunsch said.

How that philosophy evolved over time can be seen in the differences from the company’s first plant, the Schuylkill Generating Station , which was built in 1903 and was essentially an “arched brick box” compared with the strong “Neo-Roman colossus” of generating stations built along the Delaware more than a decade later, he said.

Comparisons to the old Penn Station

Consider, for instance, the Port Richmond Generating Station , which was built in 1925 and was shut in 1984. Industry publications once described it as “The Most Handsome Station in America.”

A University of Pennsylvania historic preservation report about potential uses of the site said the plant “merged the aesthetic and cultural power of beaux-arts design with latest technology to generate power to run the industries that earned Philadelphia the title of ‘The Workshop of the World.’”

The plant was designed by the PECO engineer W.C.L. Eglin and the architect John Torrey Windrim, the report said, adding that “its monumentality and classical aesthetics intentionally associate technological innovation with notions of permanence and tradition.”

Wunsch described the Port Richmond station as “spectacular,” and with its vaults and capacity for letting in huge amounts of natural light, closest in look and feel to the Penn Station of old in New York City.

Among the reasons these plants were built on the Delaware: Coal could be brought by barge and the river water used for condensing and cooling the huge turbines.

While Wunsch lauded these architectural marvels, he said the environmental damage they caused cannot be overlooked. PECO disposed of toxic coal ash loaded with poisons such as mercury that filled entire islands in the Delaware, he said.

Dangerous places to visit

Berindei said he’s visited about 50 abandoned power plants around the world and they’ve become his favorite places to explore.

Berindei, with his fellow urban explorer Bryan Weissman, are known as The Proper People , a nod to a sign posted at a property they once visited that declared “Access Prohibited Except by the Proper People.”

They visited the Port Richmond generating station in Philadelphia , which has been used for scenes in movies such as “ Transformers 2,” “The Last Airbender” and “12 Monkeys.”

The video of their visit shows them treading carefully throughout the plant. They note – in more than a bit of understatement – that “this place is extremely dangerous” after the camera zooms in on a concrete chunk of ceiling dangling precariously high above them.

At another point, as they walk over some rusted grates, they joke, “These grates are not great.”

The power plants were built to echo the sense of strength and gravitas of the monuments in Washington, D.C., Berindei said. As such, many power stations in their day offered public tours or even had observation areas where visitors could watch the inner workings.

Berindei said he relies on old trade journals and advertisements of the time to put these buildings in their proper time and place. “Once you’ve experienced a place like this, it’s begging to be contextualized,” he said.

Weissman and Berindei also visited the Southwark Generating Station, which they called a “lesser-known gem” in a videotaped visit .

They described the Southwark plant as an “icon of progress” and as a “landmark structure that was the beating heart of a city.” Southwark, which was built in the 1940s, was emblematic of post-war optimism and a “monument of its time,” they said.

A video of the site shows painting peeling from a door in such a way as to resemble a warped world map.

Beyond the large-scale industrial machinery, the video hints at the humans who once populated Southwark: Footage shows a daily calendar book from 1977 and a jar of Coffee Mate still on a shelf in an employee break room.

Some power plants find a new life

Not all of the plants have been gutted and abandoned. There have been creative ideas for adaptive re-uses.

The Chester Waterside Station in Chester in Delaware County, Pa., which was completed in 1919 and was finally shut down in 1987, was remediated and redeveloped into office space. And permits for the redevelopment of another former power plant, the Delaware Generating Station , into housing units have been issued, the website Philadelphia YIMBY reported in January .

The Schuylkill station, which became an oil-burning plant owned by the power company Exelon, was retired at the end of 2012, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported .

It’s unclear what the future might hold for the Port Richmond and Southwark sites. Exelon, which now owns those sites, did not respond to a request for comment.

During their visits, Weissman and Berindei have faced an array of environmental hazards, such as exposure to PCBs, lead paint and mercury, mold, asbestos and pigeon droppings.

Why risk their health like that?

Berindei said that, after doing urban exploring for seven years, he’s concluded that it’s a chance to bear witness and document places that would otherwise be lost to destruction.

During the pandemic, there has been a worldwide “slaughter” of abandoned industrial sites because scrap metal prices have skyrocketed, leading to scavenging and gutting, Berindei said.

He added that visiting sites like those on the Delaware gives rise to a “solemn sense” that “we’re never going to build something like this again because the world is so disposable because of the bottom line.”

Chris Mele is a reporter and editor with more than 30 years of experience in news, specializing in investigative and enterprise reporting.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Recent Stories

Delaware River sojourners revel in nature and camaraderie

Battleship New Jersey is welcomed back to Camden after dry dock repairs

SS United States faces being scrapped after losing berth battle in Philadelphia

New marina and entertainment complex planned in Northeast Philadelphia

Guest column: No national park at DWGNRA

Studio A: Event Space

Let our beautiful boutique venue be home to your next special event! Perfect for Weddings, corporate events or cocktail parties, our airy studio is a unique space to fit your unique style!

SPACE DETAILS

Capacity 110 Seated: at this number, we recommend family style or plated dinner. 140 Cocktail: A popular option to expand attendance capacity

Formal or informal ceremony options

Tech In house PA system and projection abilities. Additional microphone rentals available upon request.

Catering your event is simple in our commercial style kitchen. Our space has ample room for cooking, plating, and preparing for the next course! Ask about renting our kitchen space to complete your event.

- Two commercial style gas range NXR ovens

- Two dishwashers

- Chest freezer

- Two refrigerators

Yokota AB Combined Heat & Power Plant Tour

Come get the inside scoop on one of the newest modern cogeneration heat and power plants! Tour is free, but you pay your own way for lunch.

Registration is required for base access. After registering your information,

please send a copy of your photo ID (Driver’s license or My Number card) to [email protected] i n order to complete your registration.

Do not forget to bring the same photo ID on the day of the tour.

Two time slots are available for the tour.

Morning tour: Jul 09, 2024, 9:30 AM – 12:30 PM

0930: Meet at Yokota Gate 2 (Main Gate) , Ishihata, Mizuho, Nishitama District, Tokyo, Tokyo 190-1211, Japan

10:00 Morning Tour

11:00 Lunch at Chili's restaurant on base!

Register here!

https://www.samejapan.org/event-info/yokota-ab-combined-heat-power-plant-tour-1000-tour-1100-lunch

Afternoon tour: Jul 09, 2024, 10:30 AM – 2:00 PM

1030: Meet at Yokota Gate 2 (Main Gate), Ishihata, Mizuho, Nishitama District, Tokyo,

Tokyo 190-1211, Japan

12:30 Afternoon Tour

https://www.samejapan.org/event-info/yokota-ab-combined-heat-power-plant-tour-1100-lunch-1230-tour

Recent Posts

Happy International Women in Engineering Day!

On Sunday, 23 June, the SAME Japan Post honors the remarkable contributions of female engineers worldwide (and frankly all the women that surround us working in the Architect, Engineer, and Constructi

Ebisu Beer Night with AIA Japan

Last-minute real-time venue change -- AIA and SAME overwhelmed the venue, so moved to a larger one -- Yona Yona at https://maps.app.goo.gl/d5KxhfLPBz7MXLAK8 ******** How many architects does it take t

2024 SAME Japan Industry Forum 2024 SAME Japanインダストリーフォーラム (10/22-24)

Registration for Sponsors and individual members and guests is finally here! Please review our website and start your registration underway today! Remember, sponsoring companies, that your sponsorsh

- Podcast Home Page

- Show Notes Listing

- Forest Haven

- Lincoln Way

- The SS United States

- Fallside Hotel

- Pleasure Beach and Long Beach

- Taunton State Hospital

- Randall Park Mall

- Gary, Indiana

- Six Flags New Orleans

- The Destruction of Our Lady

- The Lost Garden of Beatrix Farrand

- Skin Experiments at Holmesburg Prison

- The Story of Urban Exploration Resource

- Ninjalicious and Infiltration.org

- The Life & Death of the American Mall

- What Happened To Brownsville

- Myths & Realities of Chernobyl

- Is Keepling Locations Secret Important?

- The Catskill Game Farm

- Abandoned Resorts of the Catskills

- The Tragedy At Third Presbyterian Church

- Losing Our Religion - Abandoned Churches

- Exploring Danvers State Hospital

- The Closure of the State Hospitals

- Why Were The Asylums Built?

- The Victory Theatre

- The Rise And Fall of American Theaters

- ABANDONED AMERICA ABROAD

- ENTERTAINMENT & COMMERCE

- HEALTH CARE

- HOMES & NEIGHBORHOODS

- HOTELS & RESORTS

- MISCELLANIA

- RELIGIOUS SITES

- SCHOOLS & RESEARCH

- LATEST ADDITIONS

- Leap of Faith 2024 Photo Workshop

- Dunnington Mansion Photo Workshop

- Prints, Mugs, and Other Goodies

- Signed "Age of Consequences"

- Books On Amazon

- MAILING LIST

Richmond Generating Station

The floor of the turbine hall in Philadelphia's abandoned Richmond Generating Station

Look around Richmond's turbine hall by clicking and dragging the image.

Join us on Patreon for high quality photos, exclusive content, and book previews Read the Abandoned America book series: Buy it on Amazon or get signed copies here Subscribe to our mailing list for news and updates

Travel with Rick Steves

Listen live.

Living on Earth

Living on Earth is an environmental news and information program. Each week host Steve Curwood guides the listener through a mix of news, features, interviews and commentary on a broad range of ecological issues.

- Urban Planning

- Preservation

Peeking at a powerful past

- PlanPhilly staff

Richmond power station photos by Exelon spokesman Fred Maher

By John Davidson For PlanPhilly

Of all the remnants of Philadelphia’s industrial past along the Delaware waterfront, the Port Richmond and Delaware power generation stations stand out as classical, imposing monuments to early 20th century industry.

Designed by John T. Windrim and W.C.L. Eglin, the Delaware station was completed in 1917 and the Port Richmond station in 1925. Together, these coal-fired power plants fueled the vibrant manufacturing industry of North Philadelphia with the most state-of-the-art machinery and engineering. At its peak, the Port Richmond station’s four huge steam turbines had a capacity of 600 megawatts.

But now these vaulted glass and steel buildings sit in ruins on the river’s edge. PECO still occasionally operates out of a section of the Delaware station during periods of peak power use, but the Port Richmond station is completed vacant. It closed as a full-time power plant in 1984 and since then its primary use has been as a set for big budget Hollywood films such as 12 Monkeys, Transformers 2, and most recently, The Last Airbender, which completed filming at the plant last month.

And no wonder: Hollywood can’t build sets like the Port Richmond station, no matter how big the production budget might be. The station’s massive boilers, turbine hall and electrical rooms have been re-imagined as futuristic psych wards, time machines, spaceships, and for several weeks last year during the filming of Transformers 2, as the Decepticons lair.

Ironically, the former power station no longer has power, so when film crews come to town they must set up huge generators in the parking lot. “When they come in here to film the place get’s lit up like a shopping mall,” says Exelon Asset Manager Mark Wilson.

Part of Wilson’s job is to keep the building stable and secure–not just for film crews but also because Exelon isn’t certain about the derelict facility’s fate. Despite rumors last year that Exelon was planning to demolish the Delaware station, which sits directly north of Penn Treaty Park, spokesman Fred Maher says the company’s current position on both the Delaware and Port Richmond stations is status quo.

“We’re holding it until we figure out what we’re going to do with it,” Maher says. “There’s been no decisions made on selling it, demolishing it or anything right now.”

Any demolition at the sites, like the removal last year of the northern façade of the 1954 addition at the Delaware station, has been motivated by a concern for safety, says Maher. Although the company reportedly holds demolition permits for the Port Richmond station, it has not indicated any intention to follow through.

In the meantime, Wilson is fighting a constant battle against rogue metal scrappers, who occasionally still manage to find a way into the huge facility and remove steel and copper. In recent years, high scrap metal prices have emboldened scrappers and forced Wilson and his crew to shore up the crumbling power station by erecting steel plates over unused entryways. Exelon also maintains a high security fence and gate system for the facility, which is adjoined by a modern office building in regular use.

Part of the reason Exelon wants to keep people out, explains Wilson, is because the building is not a safe place to wander unsupervised. On a recent walk-through, Wilson pointed out numerous areas throughout the facility that, because of “25 years of decay” are structurally unsound. Without power, the interior of the station–a dizzying maze of industrial machinery and catwalks–is in pitch darkness at night.

But despite its current state of decay, the station’s combination of classic, Romanesque architecture and modern industrial machinery make it, along with its sister station a few miles south, altogether unique features of the Delaware riverfront. Some have suggested the stations be renovated and turned into museums on the model of the Tate Museum in London.

Hilary Regan, a Northern Liberties resident, has put forth the Calder Museum proposal–a plan to convert the Delaware station into a massive museum. Regan’s proposal makes reference to the $65-million conversion of the historic Chester generating station into office and event space in 2002. Developers purchased the property from PECO for a mere $1 million.

Local interest in preserving the Port Richmond and Delaware station persists. The Port Richmond plant has been–albeit unsuccessfully–nominated for the historic properties register maintained by the city’s Historical Commission, but currently neither station enjoys any kind of protection.

If nothing is done with the stations, they will certainly continue to crumble. Sections of the Port Richmond station’s vaulted ceiling above turbine hall occasionally come down, and Wilson’s crew keeps a watchful eye and maintains a huge net around the most precarious sections. Portions of the ceiling in the main hall and elsewhere are open to the elements, and standing water under the turbines rises and falls with the tides.

Film productions have not helped to preserve the building, as directors require minor changes to the building’s physical features. During the filming of Transformers 2 last year, the crew received permission to perform a controlled explosion in the turbine hall, blowing up a small glass-and-metal structure. More recently, during filming for The Last Airbender, a lower section of one of the main turbines was painted black and red and fitted with rivets to give the appearance of a ship.

But in the context of such a massive space, these alterations are relatively minor, and Exelon, via Wilson, is careful that nothing vital to the building’s structural integrity and overall character is changed.

Contact the reporter at [email protected]

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by PlanPhilly

In-depth, original reporting on housing, transportation, and development.

You may also like

Central Delaware zoning overlay | 40th and Pine update | Campbell Square’s tree sculpture | Post is hiring

12 years ago

Cramp Shipyard demo proceeds on

13 years ago

Complex saga of Cramp Machine Shop is coming to an end

14 years ago

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Power Plant Productions. 230 N. 2nd St. Philadelphia, PA . 215.592.8775. [email protected]. powerplantproductions 'Known' by @asherroth music video #shotatpowerplan. @gkelite x @jordanchiles collab: Season to Shi. We give you these 💎gems💎 shot here at Power .

Perfect for Weddings, corporate events or cocktail parties, our airy studio is a unique space to fit your unique style. Located in Philadelphia's Old City gallery district, Power Plant Productions occupies the former Wilbur Chocolate Factory. Retaining the industrial feel of an early 1900's power plant, it features original steel beams, 34 ...

A Destination with Staying Power. The Battery Philadelphia creates a powerful new way to gather. The historic icon is being brought back to life as a one-of-a-kind lifestyle campus, energizing the waterfront. ... Re-energizing Philly's Original Power Plant. ... Request a private tour of our award-winning community!

Power Plant Productions is one of Philadelphia's premier photo studio & event space - Power Plant Productions - Venue - Photography - Equipment Rental. ... Philadelphia, PA . 215.592.8775. [email protected]. powerplantproductions. A little BTS boost for your Tuesday 🎶 Artist: @

Request a Private Tour > Main Navigation. 1913. Joseph McCall, Board chairman of the Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO), purchased 8.5 acres of the Neafie & Levy Shipyard along the Delaware River for the site of a future power plant. It was the very same shipyard where the first submarine of the Civil War was constructed.

Limerick Clean Energy Center's two nuclear reactors in Pottstown, Pennsylvania can produce up to 2,317 megawatts (MW) of clean, carbon-free energy, enough electricity to power the equivalent of more than 1.7 million homes. Limerick sits on a 600-acre site and draws its cooling water from the Schuylkill River. Download Fact Sheet.

Located in Old City's gallery district, Power Plant Productions is one of the most unique event venues in Philadelphia. Urban, unconventional, interesting and inspiring, the studio occupies the former Wilbur Chocolate Factory with its historic and iconic smokestack. The building retains all of the industrial feel from this early 1900's ...

Power Plant Productions, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1,090 likes · 7,513 were here. Power Plant Productions is a beautiful warehouse venue ready to hold your next unique event. Power Plant Productions | Philadelphia PA

Philadelphia Lubert-Adler acquired the former 500,000 square foot 'Delaware River Generating Station' Power Plant, plus an adjacent 6 acres, in November 2019. The Power Plant - which is located in a Qualified Opportunity Zone - is currently being adaptively re-purposed into luxury apartments, class A office space, food & beverage venues ...

The power station opened in 1923, maybe two miles from where Ben Franklin first tried downloading electricity for Philadelphia. It soon became the biggest generator of juice for a booming city.

Editor's note: On November 3, bids for the former Philadelphia Electric Company's Delaware Generating Station will officially close and a new owner of the massive Fishtown power plant will be revealed. Towering above Penn Treaty Park, the 223,000 square foot plant, almost a thousand feet of waterfront, and the 16.4 acres it resides on has a staggering—if not down right intimidating ...

Located directly across the street from Power Plant, Old City Parkominium offers our clientele a preferred discount. Managed by Park America 231 N 2nd Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 238-1334. Other nearby parking facilities Holiday Inn at Penns Landing. 100 N Christopher Columbus Blvd, Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 568-4025. 304 Race St ...

Factories are one of the many reminders of our state's prized industrial heritage. From coins and motorcycles to potato chips and chocolate, many Pennsylvania factories offer tours and are the perfect places to find Made-in-PA keepsakes.

Station A-2 contained two generators that produced a combined 65,000 kilowatts of power - and helped power the Workshop of the World . 1914 rendering of A-2. The Schuylkill Station continued to evolve throughout the 20th and 21st Centuries. Co-generation of steam and electricity for heating systems around the city began in 1950.

The new book Palazzos of Power: Central Stations of the Philadelphia Electric Company, 1900-1930 explores the history and present state of the vast, ... The Delaware Station Power Plant, ...

The plant's two 507 foot tall natural-draft hyperbolic cooling towers make LGS easily recognizable from miles around. Limerick's two boiling water reactors, designed by General Electric, together are capable of producing 2,317 net megawatts of power. Unit 1 began commercial operation on February 1, 1986 and is licensed to operate through 2044 ...

The circa 1953 addition, along with the oil tanks, were abated and demolished beginning in August 2009. 5 Exelon then tapped Binswanger real estate brokerage to sell the Delaware Power Station, excluding a one-acre gas turbine plant, in the fall of 2014. 4. In August 2015, developer Bart Blatstein and business partner Joseph Volpe, of the ...

Monumental structures that tower over the industrial landscape in Philadelphia, the aging central power stations of the Philadelphia Electric Company look like Metropolis meets Ancient Greece, ornate temples of stacked brick, soaring arches, and early industrial grit. But these hulking structures hide a more interesting backstory about how design can be enlisted to shape public perception.

The Schuylkill station, which became an oil-burning plant owned by the power company Exelon, was retired at the end of 2012, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported. It's unclear what the future might hold for the Port Richmond and Southwark sites. Exelon, which now owns those sites, did not respond to a request for comment.

230 N. 2ND STREET | PHILADELPHIA PA 19106 | 215.592.8775. Facebook; Instagram; Email; Power Plant Events; Planning your Event. Event Spaces; FAQ; Gallery; Location; Event Inquiry; Photo Production; Studio A: Event Space. Let our beautiful boutique venue be home to your next special event! Perfect for Weddings, corporate events or cocktail ...

Come get the inside scoop on one of the newest modern cogeneration heat and power plants! Tour is free, but you pay your own way for lunch.Registration is required for base access. After registering your information,please send a copy of your photo ID (Driver's license or My Number card) to [email protected] in order to complete your registration. Do not forget to bring the same photo ID ...