Patient Visit Summary Template

Empower patients with our comprehensive Patient Visit Summary Template, featuring crucial details for effective healthcare management. Download now!

By Karina Jimenea on Jun 20, 2024.

Fact Checked by RJ Gumban.

What is a Patient Visit Summary?

Have you ever left a medical appointment feeling uncertain about what was discussed or what steps to take next? It's a common experience for many of us. That's where a patient visit summary comes in.

A concise patient visit summary is a brief document that summarizes your recent medical appointment. It includes essential clinical information such as diagnoses, treatments, and medications discussed during the visit. Think of it as a guide to help you navigate your healthcare journey after leaving the doctor's office.

You'll typically find details about your health history within a patient visit summary, including any relevant past medical issues or ongoing conditions. It may also outline any procedures or tests performed during your visit and the results.

One of the critical components of a patient visit summary is the after-visit summary, which outlines the next steps recommended by your healthcare provider. This could include future appointments, specialist referrals, or instructions for managing your condition at home.

Additionally, the document may contain important office contact information for reaching your healthcare providers in case of questions or concerns. This ensures that you have access to support even after you've left the clinic or hospital.

Patient visit summaries are typically generated from electronic health record systems of medical practices. They are provided to patients either in printed form or electronically, depending on patient consent and the medical practices of the healthcare provider.

By providing patients with a clear and comprehensive overview of their visit encounters, patient visit summaries empower individuals to take control of their health and follow through on clinical instructions. They are a valuable tool for improving communication between patients and their health professionals and promoting continuity of care across medical appointments.

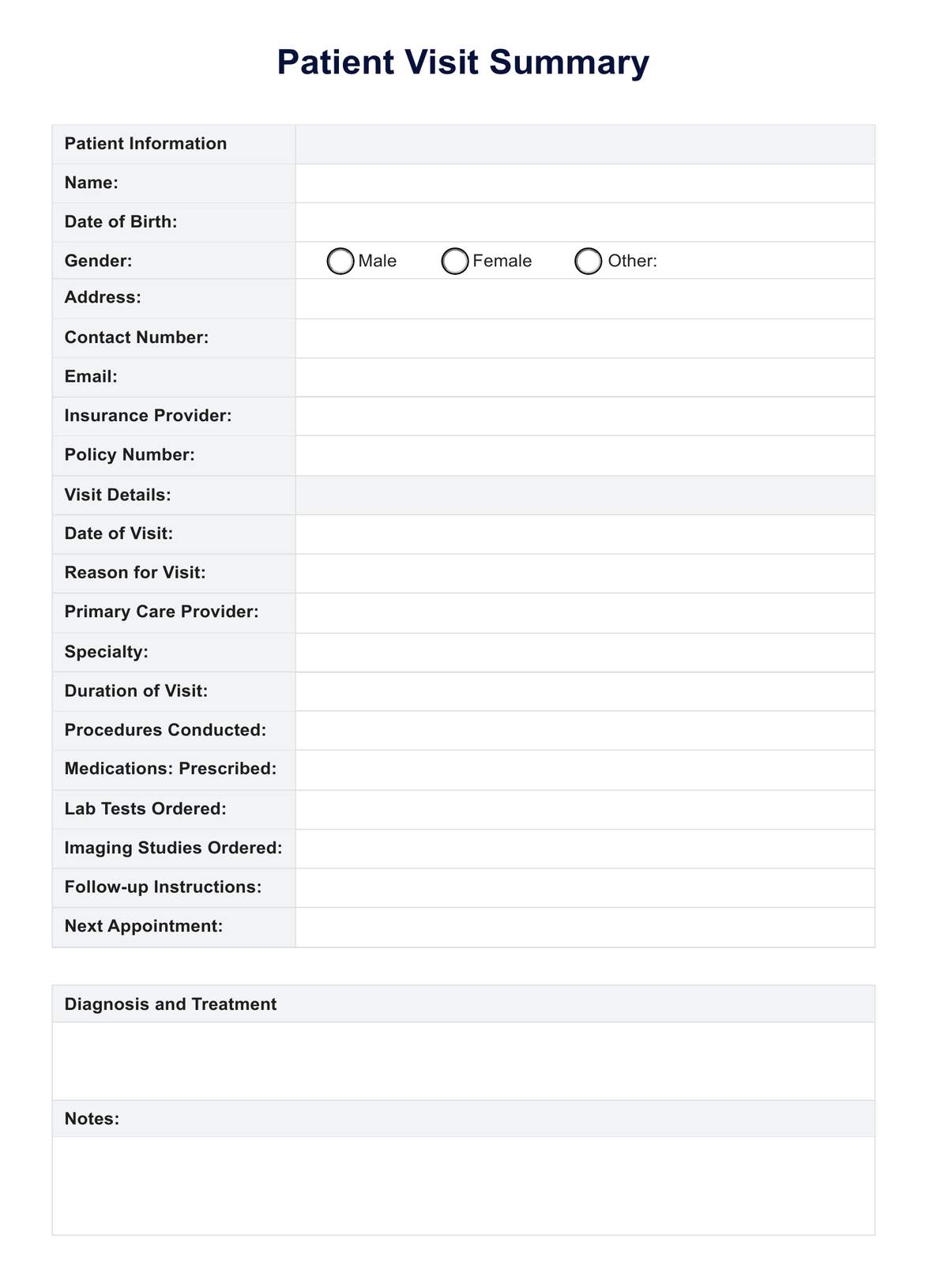

Printable Patient Visit Summary Template

Download this Patient Visit Summary Template to gain insight into organising healthcare information, empowering tto manage health better and communicate with providers.

Why is it important for healthcare professionals to summarize patient visits?

Summarizing patient visits is crucial for healthcare professionals to ensure effective communication and continuity of care.

- Facilitates clear communication : Summaries distill complex medical information into concise, understandable formats, enhancing communication between healthcare providers and patients.

- Promotes continuity of care : By documenting key findings and treatment plans, summaries enable seamless transitions between different healthcare settings and providers, ensuring consistent and coordinated care.

- Enhances patient engagement : Giving patients summaries of their visits empowers them to participate actively in their care, promoting better health outcomes through improved understanding and adherence to treatment plans.

What can you usually find in a patient visit summary?

A patient visit summary encapsulates crucial information from your medical appointment. Within this document, you'll find essential details that empower you to understand and manage your health effectively.

Diagnoses and treatment

The patient visit summary typically includes details of any diagnoses made during the appointment and the corresponding treatment plan prescribed by the healthcare provider. This section clarifies the medical conditions identified and the steps recommended to address them.

Medications prescribed

It outlines any medications the healthcare provider prescribes during the visit, including the prescription's dosage, frequency, and duration. This information helps patients understand their medication regimen and ensures proper adherence to treatment.

Procedures conducted

This section lists any procedures or tests performed during the appointment and relevant findings or results. It gives patients insight into the diagnostic process and any necessary follow-up actions.

Lab tests and imaging studies ordered

The patient visit summary includes details of any laboratory tests or imaging studies ordered by the healthcare provider and instructions for obtaining the results. This helps patients stay informed about their healthcare needs and facilitates coordination with diagnostic facilities.

Follow-up instructions

It outlines specific instructions the healthcare provider provides, such as dietary recommendations, lifestyle modifications, or self-care practices. This section guides patients on steps after the appointment to support their ongoing health management.

Next appointment

The summary specifies the date and time of the patient's next appointment, if scheduled, ensuring continuity of care and timely follow-up with the healthcare provider. This helps patients plan their future healthcare appointments and ensures they stay on track with their treatment plans.

Additional Notes

This section allows for any additional information or comments from the healthcare provider to be documented, providing further context or clarification on the visit. It ensures comprehensive communication between the healthcare team and the patient, promoting patient engagement and understanding.

How does our Patient Visit Summary Template work?

This guide simplifies patients' processes to organize and manage their medical information effectively.

Step 1: Download the template

First, access the Patient Visit Summary Template as a downloadable PDF document. Click on the provided link to initiate the download process to your device, ensuring you have a copy readily available for use. You may also print it at your patient's request, providing them with a tangible copy for their records or personal reference.

Step 2: Enter patient information

Once downloaded, the next step involves filling in your details in the designated fields. These details include your full name, date of birth, gender, address, contact number, email address, insurance provider, and policy number. Accurate completion of this section ensures that your medical records are correctly identified and maintained.

Step 3: Provide visit details

After inputting your personal information, document the patient's recent visit to the clinic or hospital. This includes entering the date of the visit, stating the reason for the visit, specifying the primary care provider, indicating any specialty involved (if applicable), detailing the duration of the visit, and listing any procedures conducted during the appointment.

Additionally, record any medications prescribed, lab tests ordered, imaging studies requested, follow-up instructions given, and schedule your next appointment.

Step 4: Diagnosis and treatment

In this section, accurately document any diagnoses provided by your healthcare provider during the visit. Correspondingly, outline the treatment plan recommended or prescribed to address the diagnosed condition(s). Include details regarding any medications prescribed, lifestyle modifications advised, or further diagnostic tests ordered for ongoing management.

Step 5: Notes

Use this space to jot down any additional information or instructions provided by your healthcare provider during the visit. This could include recommendations, advice, reminders, or pertinent discussions regarding your health and well-being. Capturing these details ensures you have a comprehensive visit record for future reference.

Step 6: Save and organize

Upon completing the template, save the document on your device for easy access and retrieval. Organizing your medical records systematically is recommended by creating a dedicated folder for storing each visit summary. This approach ensures that your medical information is readily accessible when needed.

Step 7: Share with healthcare providers

During subsequent appointments or consultations with your medical practitioners, share the completed Patient Visit Summary Template to provide them with relevant details from your visit. Sharing your medical history, chief complaints, treatment plans, and follow-up instructions enables your healthcare team to provide informed and coordinated care tailored to your needs.

Patient Visit Summary Template example (sample)

Explore our Patient Visit Summary Template example featuring responses designed to give you a clear understanding of how to utilize it effectively. Gain insight into organizing your healthcare information, empowering you to manage your health better and communicate with your providers.

Download our free Patient Visit Summary Template example here:

The benefits of documenting patient visit summaries

Documenting patient visit summaries offers numerous benefits in healthcare coordination and patient care.

- Comprehensive visit information : Summaries consolidate visit information, ensuring patients and healthcare providers can easily reference all pertinent details in one document.

- Efficient data collection : By systematically collecting data from each visit, summaries create a comprehensive patient health record, enabling better-informed medical decisions.

- Enhanced care coordination : Summaries facilitate care coordination among healthcare providers by providing a detailed patient visit report, ensuring seamless transitions between different aspects of care.

- Meaningful use of data : Healthcare providers can utilize visit summaries to identify patterns and trends in patient health, enabling them to tailor care requirements to meet specific needs effectively.

- Improved patient understanding : By providing patients with a clear and concise visit report, summaries empower them to understand their health status and actively participate in their care journey.

Why use Carepatron as your clinical documentation software?

At Carepatron, we understand the importance of clinical documentation software in modern healthcare. That's why we've developed a comprehensive solution to streamline patient visit summaries and enhance healthcare delivery.

- Telehealth integration : Seamlessly incorporate telehealth capabilities into patient visit summaries, enabling convenient virtual consultations.

- Comprehensive clinical documentation : Benefit from a robust electronic health record (EHR) system that streamlines documentation, ensuring accuracy and compliance.

- Efficient scheduling : Easily manage appointments and streamline scheduling processes, maximizing patient and provider efficiency.

- Interactive patient portal : Engage patients with an intuitive patient portal where they can securely access records like visit summaries, schedule appointments, and upload documents.

- Convenient payments : Simplify payment processes with integrated payment solutions, providing patients with a hassle-free billing experience.

With our platform, you can enhance patient care, improve efficiency, and drive practice growth effortlessly. Experience the Carepatron advantage today!

Both patients and healthcare providers utilize patient visit summaries to keep track of visit details and facilitate communication.

Patient visit summaries ensure critical information from medical appointments is documented and easily accessible for future reference and care coordination.

Patient visit summaries should be used after every medical appointment to capture essential information, facilitate continuity of care, and empower patients to manage their health actively.

Commonly asked questions

Related templates.

Popular Templates

Join 10,000+ teams using Carepatron to be more productive

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Providing Clinical Summaries to Patients after Each Office Visit: A Technical Guide

Related Papers

BMC Health Services Research

Traci Capesius

Journal of Clinical Lipidology

James Underberg , Jerome Cohen

Journal of General Internal Medicine

Asia Friedman

The use of electronic health records (EHR) is widely recommended as a means to improve the quality, safety and efficiency of US healthcare. Relatively little is known, however, about how implementation and use of this technology affects the work of clinicians and support staff who provide primary health care in small, independent practices. To study the impact of EHR use on clinician and staff work burden in small, community-based primary care practices. We conducted in-depth field research in seven community-based primary care practices. A team of field researchers spent 9-14 days over a 4-8 week period observing work in each practice, following patients through the practices, conducting interviews with key informants, and collecting documents and photographs. Field research data were coded and analyzed by a multidisciplinary research team, using a grounded theory approach. All practice members and selected patients in seven community-based primary care practices in the Northeastern US. The impact of EHR use on work burden differed for clinicians compared to support staff. EHR use reduced both clerical and clinical staff work burden by improving how they check in and room patients, how they chart their work, and how they communicate with both patients and providers. In contrast, EHR use reduced some clinician work (i.e., prescribing, some lab-related tasks, and communication within the office), while increasing other work (i.e., charting, chronic disease and preventive care tasks, and some lab-related tasks). Thoughtful implementation and strategic workflow redesign can mitigate the disproportionate EHR-related work burden for clinicians, as well as facilitate population-based care. The complex needs of the primary care clinician should be understood and considered as the next iteration of EHR systems are developed and implemented.

Journal of healthcare risk management : the journal of the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management

Dean F Sittig

Although electronic health records (EHRs) have a significant potential to improve patient safety, EHR-related safety concerns have begun to emerge. Based on 369 responses to a survey sent to the memberships of the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management and the American Health Lawyers Association and supplemented by our previous work in EHR-related patient safety, we identified the following common EHR-related safety concerns: (1) incorrect patient identification; (2) extended EHR unavailability (either planned or unplanned); (3) failure to heed a computer-generated warning or alert; (4) system-to-system interface errors; (5) failure to identify, find, or use the most recent patient data; (6) misunderstandings about time; (7) incorrect item selected from a list of items; and (8) open or incomplete orders. In this article, we present a "red-flag"-based approach that can be used by risk managers to identify potential EHR safety concerns in their institutions. An orga...

Emily Patterson , A. Gurses , Ant Ozok

Proceedings of the ACM international conference on Health informatics - IHI '10

Maria Souden

Isomi Miakelye , Greg Orshansky

Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association

Jason Thompson

Marina DI COSTANZO

Evidence report/technology assessment

Brian Hemens , Sue Troyan

The objective of the report was to review the evidence on the impact of health information technology (IT) on all phases of the medication management process (prescribing and ordering, order communication, dispensing, administration and monitoring as well as education and reconciliation), to identify the gaps in the literature and to make recommendations for future research. We searched peer-reviewed electronic databases, grey literature, and performed hand searches. Databases searched included MEDLINE®, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Compendex, Inspec (which includes IEEE Xplore), Library and Information Science Abstracts, E-Prints in Library and Information Science, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, and Business Source Complete. Grey literature searching involved Internet searching, reviewing relevant Web sites, and searching electronic databases of grey lite...

RELATED PAPERS

BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making

Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM

Steven Ornstein , Andrea Wessell

… of internal medicine

Ernest Imoisi

Taya Irizarry

Brendaly Rodriguez

American Journal of Preventive Medicine

David Ahern

Emily Patterson , Patricia Abbott

Dr Paul Barach

International Journal of Medical Informatics

Brad Doebbeling

AMIA ... Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium

Paulina Sockolow

Implementation Science

Alex Krist , David Chambers , Bijal Balasubramanian

Mindy Flanagan

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Journal of Biomedical Informatics

Lipika Samal

Juha Mykkänen

Joint Commission journal on quality and patient safety / Joint Commission Resources

Hector Rodriguez

Richard Marken

Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA

Seth Meltzer

Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 4 (2016) 437-450

Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology

James Slaven

Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing

Sharon Harris

The Journal of Rural Health

Kimberly Galt , James Bramble , Mark Siracuse

Sumit Mohan , Demetra Tsapepas

Jonathan Teich

Roger Chaufournier

Gerald Elysee, PhD

2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences

Sajda Qureshi

intansari adiningrum

Neil Carlson

Karthik Natarajan

Joseph Kannry

Bond Caniago Anshar Bonas Silfa

Human Factors and Ergonomics

Tommaso Bellandi

Western journal of nursing research

Kimberly Galt

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Certification of Health IT

Health information technology advisory committee (hitac), health equity, hti-1 final rule, information blocking, interoperability, patient access to health records, clinical quality and safety, health it and health information exchange basics, health it in health care settings, health it resources, laws, regulation, and policy, onc funding opportunities, onc hitech programs, privacy, security, and hipaa, scientific initiatives, standards & technology, usability and provider burden, providing clinical summaries to patients after each office visit: a technical guide.

This document is a guide to help eligible professionals and their organizations gain a better grasp of how to successfully meet the criteria of giving clinical summaries to patients after each office visit. It discusses the two requirements to accomplishing these goals and assists organizations in meeting them.

- Assuring that the information for the AVS has been entered, updated, and validated in the EHR before the end of the visit.

- Developing process steps for assuring that each patient receives an AVS before the end of the visit.

The material in these guides and tools was developed from the experiences of Regional Extension Center staff in the performance of technical support and EHR implementation assistance to primary care providers. The information contained in this guide is not intended to serve as legal advice nor should it substitute for legal counsel. The guide is not exhaustive, and readers are encouraged to seek additional detailed technical guidance to supplement the information contained herein.

Reference in this web site to any specific resources, tools, products, process, service, manufacturer, or company does not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

4 votes with an average rating of 2

Open Survey

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Reasons to publish with us

- About Family Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conclusions, declaration, acknowledgement.

- < Previous

After-visit summaries in primary care: mixed methods results from a literature review and stakeholder interviews

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Courtney R Lyles, Reena Gupta, Lina Tieu, Alicia Fernandez, After-visit summaries in primary care: mixed methods results from a literature review and stakeholder interviews, Family Practice , Volume 36, Issue 2, April 2019, Pages 206–213, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmy045

- Permissions Icon Permissions

After-visit summary (AVS) documents presenting key information from each medical encounter have become standard in the USA due to federal health care reform. Little is known about how they are used or whether they improve patient care.

First, we completed a literature review and described the totality of the literature on AVS by article type and major outcome measures. Next, we used reputational sampling from large-scale US studies on primary care to identify and interview nine stakeholders on their perceptions of AVS across high-performing primary care practices. Interviews were transcribed and coded for AVS use in practice, perceptions of the best/worst features and recommendations for improving AVS utility in routine care.

The literature review resulted in 17 studies; patients reported higher perceived value of AVS compared with providers, despite poor recall of specific AVS content and varied post-visit use. In key informant interviews, key informants expressed enthusiasm for the potential of using AVS to reinforce key information with patients, especially if AVS were customizable. Despite this potential, key informants found that AVS included incorrect information and did not feel that patients or their practices were using AVS to enhance care.

There is a gap between the potential of AVS and how providers and patients are using it in routine care. Suggestions for improved use of AVS include increasing customization, establishing care team responsibilities and workflows and ensuring patients with communication barriers have dedicated support to review AVS during visits.

Spurred by US health care reform and the subsequent Meaningful Use financial incentives, many US health care systems and clinicians have implemented electronic health records (EHRs) that adhere to specific requirements. This includes the requirement to provide a written clinical summary from the EHR to patients after each clinical encounter ( 1 )—referred to as an after-visit summary (AVS). AVS have had a rapid introduction into clinical practice ( 2 ), given that the vast majority of US hospitals (94%) and office-based health professionals (77%) met Stage 1 Meaningful Use metrics in 2014 ( 3 , 4 ), of which AVS was a core component. Even with impending changes to the Meaningful Use program in the coming years ( 5 ), the current practice of visit summaries in primary care is likely to continue as a part of patient-centred care, especially since consumers are now accustomed to written encounter summaries.

By providing patients with a written record of medical decisions and care plans, the use of AVS has the potential to improve patient knowledge, self-management and patient–provider communication. Numerous studies have documented barriers patients face in understanding and remembering information about their treatments and care plans after a visit ( 6–9 ). In particular, AVS use may hold great potential in addressing the well-documented barriers to patient–provider communication and shared decision making faced by vulnerable patients with limited health literacy and limited English proficiency ( 10–14 ). Despite this potential, there is limited research that explores AVS implementation in clinical practice and how its use has impacted patient and provider outcomes.

Because of the paucity of information available, there were two complementary objectives of this study: (i) to explore the existing literature on the current use of AVS and (ii) to gain perspectives from clinical leaders about the current implementation and potential for integrating AVS into clinical practice. In particular, we sought to integrate findings from these objectives, with a specific focus on vulnerable patient populations.

Literature review

In January 2018, we conducted a comprehensive search on PubMed to identify articles from the queries ‘after visit summary’, ‘visit summary’, ‘visit discharge’ and ‘clinical summary’. Papers were included if they (i) were published in English language and (ii) represented research conducted in the USA (where the term AVS is most commonly used). We excluded papers if (i) they mentioned the term AVS (such as being listed as one of many related EHR tools) but did not provide any data on AVS use specifically or (ii) if they were referring to a broader process of visit communication that did not involve the standardized AVS tool. We also reviewed the references lists of included articles to identify additional studies with a focus on AVS use. Although we had a specific interest in the impact of AVS use among vulnerable patients, we conducted a broad literature review on AVS because there were few studies identified overall.

The included articles were categorized by study type, as there was wide variation in the research goals. For example, several studies focused on provider perceptions/use of the AVS, which varied greatly from studies assessing the readability of the document or longer term patient understanding of the information provided. We also categorized the research methods employed as higher (e.g. trials, strong comparison groups) versus lower quality (e.g. case studies, lack of comparison group). Finally, within each type of research study, the small sample size of the included articles allowed us to directly summarize the major findings and provide examples of the key outcomes examined.

Key informant interviews

To complement this literature review, we also conducted a small qualitative study among leaders in primary care about their perceptions of AVS use in routine practice. Rather than using a random sampling approach that might have captured practices without any current routine AVS use, we instead used purposive sampling to identify a sample of leaders in high-performing primary care practices more likely to be attesting for Meaningful Use certification in their practices. Specifically, we first used reputational sampling from published literature of large demonstration projects that systematically identified high-performing sites in both academic and safety primary care sites ( 15 , 16 )—identifying and interviewing experts who had recently completed multiple site visits and in-depth observations of primary care practices nationally (including variation by region and practice type). We then used snowball sampling to identify the remaining key informants, ensuring that a significant portion (at least 1/3) of key informants were leaders or had extensive experience working with safety net health care settings, as this was a major objective of our study. This selection process did not target positive versus negative opinions of AVS use specifically, as interviewees had experience with AVS in practice that could have differed substantially from one another. In total, we conducted interviews with key informants from nine primary care sites, concluding after we had reached thematic saturation of the current types of AVS use.

We used a semi-structured interview guide to gain perspectives about (i) current AVS practices within their system (e.g. who is responsible for AVS distribution, the process for distributing AVS and how AVS information is customized), (ii) the potential of AVS to improve patient knowledge and outcomes within their system and more broadly across primary care systems nationwide, (iii) strategies to improve the use of AVS and (iv) specific considerations for using AVS for the care of individuals with limited English proficiency and limited health literacy.

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. We used descriptive qualitative methods ( 17 ) to organize, categorize and code the transcripts across all of the major interview discussion topics. More specifically, we coded discrete information provided in the interviews into categories (such as the staff member responsible for AVS distribution at each site, the AVS features used the most, the AVS features viewed as least useful), as well as used thematic coding to capture broader ideas about team-based care, workflows and other topics that could influence the impact of AVS use in clinical care. All four co-authors conducted the key informant interviews and reached consensus on the final coding categories and emergent themes, and two of the co-authors (CRL and LT) completed the coding process on all transcripts once the codebook was established.

The University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board deemed this study as not classifying as human subjects research.

Our literature review resulted in 263 articles (243 from PubMed, 20 manually identified from reference lists). We excluded 246 articles, resulting in 17 final articles ( Table 1 ). We developed four major categories of studies (not mutually exclusive):

Summary of articles included in after visit summary (AVS) literature review

EHRs, electronic health records; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

1. Case studies of implementation ( 15 , 18–22 );

2. Qualitative/quantitative assessments of patient perceptions ( 23–30 );

3. Qualitative/quantitative assessments of clinician perceptions ( 18 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 31 );

4. Observational studies or interventional research ( 25 , 32 , 33 ).

A substantial number of these studies used less rigorous methodological designs (such as convenience samples with pre-post self-reported measures); but 8 of the 14 studies ( 23–29 , 31 ) employed in-depth survey, qualitative or experimental methods.

Examples or case studies of AVS implementation in real-world practice

The articles examining implementation of AVS emphasized team-based approaches that utilized standard workflows. One study encouraged team-based responsibility, with nurses and medical assistants (MAs) delivering the AVS and care plan at the conclusion of the visit ( 15 ). Another study discussed the potential to integrate AVS into a health coaching model, using the AVS document as a tool to assess patient understanding ( 19 ). In the three content analyses, one study found only half of AVS contained information about follow-up appointments and only a quarter contained tailored AVS sections ( 18 ), while the others found that AVS were written with complex language and at a readability level requiring a higher level of education to understand ( 22 , 34 ).

Patient perceptions of AVS

Patient perspectives on AVS were favourable. In total, four qualitative studies ( 23 , 26 , 28 , 29 ) reported that patients used the document to relay information to their families or other physicians ( 23 , 28 , 29 ). However, patients expressed concerns about the accuracy of their information ( 26 , 28 , 29 ) and the potential for privacy breaches ( 28 , 29 ). While the overall readability of the AVS was problematic in some cases ( 26 , 29 ), many patients desired more information (such as more detailed information or context about their diagnoses and treatment/disease management) ( 30 ). Quantitative studies ( 24 , 25 , 27 ) echoed these themes: a vast majority of patients found the AVS useful, but only half or fewer reported using them after the visit.

Clinician perceptions of AVS

The studies examining clinician perceptions were focused on physicians. Overall, physicians had moderately favourable views of the ease and potential of using AVS for patient care and education ( 25 , 28 , 31 ). However, they expressed concerns about the high complexity of information and the lack of tailoring to the needs of specific patients ( 25 , 26 , 28 ), particularly with regard to literacy level and language. In addition, physicians expressed concerns about not always having sufficient time during practice to update the problem list or medication list and therefore mentioned errors and extraneous information (e.g. outdated diagnostic codes) ( 31 ).

Observational or interventional research using AVS

Three articles evaluated interventions centred on clinical applications of AVS, most of which did not result in significant findings. There was high variability in whether patients reported using AVS after their initial visits, from a small minority ( 25 ) to a majority of patients who received highly personalized versions ( 32 ). A randomized controlled trial of AVS content did not find significant differences in patient adherence, satisfaction or recall of medical information when directly comparing AVS documents with varying amounts of content ( 25 ). Patients’ recall of the information on the AVS was low (only ~33% of content categories); this recall of information was unexpectedly not related to patients’ health literacy status or the amount of information displayed.

In our key informant interviews, the final sample of nine interviewees represented academic, safety net and private practices ( Table 2 ). The vast majority of participants were using the Epic EHR system in their practice (similar to many other health care settings nationwide ( 35 )), even though we did not use this as a specific inclusion criterion. Despite this, several of the participants were also able to discuss more than one EHR given their experiences with multiple site visits or their previous clinical experience prior to Epic implementation.

Summary of key informant interviewees by site and role

Current state of AVS implementation

A high-level summary of the current AVS use is found in Table 3 . Major findings included the following.

Summary of current after-visit summary (AVS) implementation by interview site

EHRs, electronic health records.

Regular distribution of AVS

Likely driven by Meaningful Use, most clinics issued a printed AVS at the majority (if not all) of visits. In addition, many clinics used the ‘patient instructions’ section of the AVS to include personalized information like counselling recommendations and guidance for self-management.

I would say it’s probably the sections that are most used by the clinician are the blank free text space where you do write out some instructions.

Patients satisfied with AVS, but might not be using it

Several interviewees talked about positive patient perceptions (mirroring the literature review results above): ‘Patients actually really, really like having the information’. However, few to no interviewees suggested that the patients referred to the AVS post-visit: ‘I think the patient treats it like they would treat any other confusing piece of paper, which is either to throw it away before they leave the clinic or after they get home’.

Clinics not using AVS for patient teaching

The majority of practices did not use the AVS in a standard way to reinforce specific information with patients, instead printing and handing it out without explanation.

I’ve yet to find anyone, anyplace where someone goes over the After Visit Summary with the patient. And I’ve asked many places [even in high-performing sites] because it seems so obvious that you want to do that in terms of closing the loop…. It’s such a terrific way to close the loop, and it’s just surprising. People just don’t do it.

Slightly less than half of interviewees did mention highlighting some information on the AVS. Yet this was not done in a standardized way across clinicians or visits.

Importance of specific features of the current AVS

When considering specific features of the AVS ( Table 4 ), almost all participants expressed that the patient instructions section was most useful because of the ability to customize information easily. The medication list (if accurate) was also mentioned as useful. Finally, upcoming visits and care plans were also highlighted as potentially important (but perhaps not always standard).

Summary of best and worst features of after-visit summary (AVS) document by interview site

Next steps: overcoming barriers

The key informants unanimously felt that AVS could improve clinical outcomes if utilized properly. When asked about future changes in the Meaningful Use program related to the AVS, interviewees did not foresee abandoning this document in practice.

I think [the AVS] could be really important. I don’t think it’s important the way it’s used now, but I think it could be extremely important and extremely helpful.

Moving forward, improvements in AVS use were related to the following themes:

Team-based workflows

Interviewees expressed that non-clinicians are well positioned to use the AVS with patients for operational next steps (like follow-up appointments). Within the one clinic with a standard MA workflow already in place, the interviewee commented, ‘MAs really like it. They like being part of the process of closing the loop and just helping the patient with those final details’. In addition, MAs or other staff could likely counsel related to lifestyle (such as diet or exercise) or other content with additional training and/or support. For example, one interviewee stated that the MA could use the AVS more effectively, but only with guidance from a provider:

The problem is the MA would have to know which part of the After Visit Summary to go over because you don’t want to go over more than like a couple of things, because people are not going to walk on practice remembering eight or 10 things.

Focus within the AVS

In addition, there were many comments related to the idea that the AVS ‘seems to want to serve too many purposes’. In addition to multiple content areas like medications and diagnoses, clinicians also wrote in personalized instructions in varying ways. Therefore, the current AVS format was long and complex, especially to find specific necessary information from a single visit. Increased ability to customize the AVS in straightforward ways was viewed as critical.

Tailoring by language and literacy

Because the AVS was not available in non-English languages or with low-literacy text, interviewees requested adjusting content to improving patient communication. For example:

For our folks that speak other languages, we are really limited in terms of written instructions we can provide for them. I don’t have any good workaround for that. If there’s a way to do like the med chart with pictures, not just all words… [The AVS is] basically four pages of words.

Among a small amount of published literature on the topic, we found that patients perceive AVS positively, but few appear to routinely refer to the document after the visit. Clinicians surveyed in the published literature were less satisfied than patients with AVS. Moreover, beyond this literature review of existing research, we also conducted our own qualitative investigation among primary care leaders about their perceptions of AVS in high-performing clinical practices. Among these key informant interviewees, we found similar implementation experiences across a varied group of primary care practices. While a hardcopy AVS were distributed in virtually all encounters, there was uncertainty about whether patients used AVS and a lack of routine practice to educate patients about AVS content. The customized patient instructions section was viewed as most useful within the AVS, but this could be buried in the midst of other content. Despite such challenges, interviewees expressed overall positivity about the potential of the AVS to improve patient understanding in the future.

This is the first study to our knowledge that comprehensively studied the current use of AVS in real-world practices in combination with stakeholder perceptions across multiple health care settings about the best ways to improve AVS use for maximum impact. While interviewees in this study provided recommendations for improving the content of AVS to improve implementation, any content changes would be insufficient without additional workflows to support patient use and understanding. Future research is needed to understand whether and how AVS contribute to improved patient outcomes (e.g. understanding/retention, clinical outcomes) and to directly compare the impact of different workflows of AVS distribution. There is no published literature about electronic delivery of AVS through online patient portals, or comparisons of digital versus printed distribution. In addition, there is a need for research to compare workflows of teach-back ( 36 ) using AVS to determine the best modes for patient understanding and retention.

Our study supports previous research on patient–provider communication. For example, patients in our literature review expressed high interest in access to information from their medical encounters via AVS, which is similar to many other studies on patient interest in and satisfaction with access to their online medical record information ( 37 , 38 ). Moreover, our findings support previous work that that training and/or tools can improve in-person communication ( 39 ), especially for vulnerable patient populations ( 40 , 41 ), but this is the first study to our knowledge of whether the AVS is being used for patient education and teach-back. Moreover, implementation of these improved communication strategies into real-world settings requires overcoming obstacles such as under-staffing and insufficient time during visits.

There are several limitations of this study. First, the literature review may have missed studies using a structured process for delivering patient education materials at the conclusion of visits or hospitalizations. In addition, our qualitative sample was small and is not broadly generalizable, and most participants gave feedback on a single EHR product. In addition, the interviewees were all providers without any patient representation. However, we reached thematic saturation with this small but diverse set of interviewees across multiple health care settings.

Moving forward, patient summaries of information like AVS will likely continue to play a role in primary care. AVS utility for both patients and clinicians will likely increase as content and design are improved. The growth of the patient-centred medical home and the emphasis on team-based care will likely result in new roles and responsibilities for communication with patients, and AVS may take centre stage in workflow redesign. Over time, as federal policies and incentives for EHR use change, AVS will survive only if clinicians and patients find them relevant and useful.

Funding: The Roundtable on Health Literacy of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provided support for our investigations into AVS. CRL is supported by AHRQ R00HS022408.

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank all the people we interviewed who contributed their time to this project.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . 2015 Meaningful Use Definitions and Objectives . http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/meaningful-use-definition-objectives ( accessed on 14 May 2015 ).

Blumenthal D , Tavenner M . The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records . N Engl J Med 2010 ; 363 : 501 – 4 .

Google Scholar

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . 2014 Hospitals Participating in the CMS EHR Incentive Programs . http://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/pages/FIG-Hospitals-EHR-Incentive-Programs.php ( accessed on 14 May 2015 ).

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . 2014 . Office-based Health Care Professional Participation in the CMS EHR Incentive Programs . http://thehealthcareblog.com/blog/2016/01/19/ehr-incentive-programs-where-we-go-from-here/ ( accessed on 14 May 2015 ).

Slavitt A , DeSalvo K . EHR incentive programs: where we go next . The CMS Blog .

Stevenson FA , Barry CA , Britten N , Barber N , Bradley CP . Doctor-patient communication about drugs: the evidence for shared decision making . Soc Sci Med 2000 ; 50 : 829 – 40 .

Roter DL , Hall JA . Studies of doctor-patient interaction . Annu Rev Public Health 1989 ; 10 : 163 – 80 .

Sarkar U , Schillinger D , Bibbins-Domingo K et al. Patient-physicians’ information exchange in outpatient cardiac care: time for a heart to heart ? Patient Educ Couns 2011 ; 85 : 173 – 9 .

Hummel J , Evans P. Providing Clinical Summaries to Patients after Each Visit: A Technical Guide . Seattle, WA : Qualis Health , 2012 .

Google Preview

Peek ME , Odoms-Young A , Quinn MT et al. Race and shared decision-making: perspectives of African-Americans with diabetes . Soc Sci Med 2010 ; 71 : 1 – 9 .

Aboumatar HJ , Carson KA , Beach MC , Roter DL , Cooper LA . The impact of health literacy on desire for participation in healthcare, medical visit communication, and patient reported outcomes among patients with hypertension . J Gen Intern Med 2013 ; 28 : 1469 – 76 .

Institute of Medicine . Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion . Washington, DC : National Academies Press (US) , 2004 .

Schillinger D . Literacy and health communication: reversing the ‘inverse care law’ . Am J Bioeth 2007 ; 7 : 15 – 8 .

Schillinger D , Bindman A , Wang F , Stewart A , Piette J . Functional health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication among diabetes patients . Patient Educ Couns 2004 ; 52 : 315 – 23 .

Sinsky CA , Willard-Grace R , Schutzbank AM et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices . Ann Fam Med 2013 ; 11 : 272 – 8 .

Wagner EH , Gupta R , Coleman K . Practice transformation in the safety net medical home initiative: a qualitative look . Med Care 2014 ; 52 ( 11 suppl 4 ): S18 – 22 .

Sandelowski M . Whatever happened to qualitative description ? Res Nurs Health 2000 ; 23 : 334 – 40 .

Salmon C , O’Conor R , Singh S et al. Characteristics of outpatient clinical summaries in the United States . Int J Med Inform 2016 ; 94 : 75 – 80 .

Bodenheimer T , Laing BY . The teamlet model of primary care . Ann Fam Med 2007 ; 5 : 457 – 61 .

Jiggins K . A content analysis of the meaningful use clinical summary: do clinical summaries promote patient engagement ? Prim Health Care Res Dev 2015 ; 17: 1 – 14 .

Kanter M , Martinez O , Lindsay G , Andrews K , Denver C . Proactive office encounter: a systematic approach to preventive and chronic care at every patient encounter . Perm J 2010 ; 14 : 38 – 43 .

Colorafi K , Moua L , Shaw M , Ricker D , Postma J . Assessing the value of the meaningful use clinical summary for patients and families with pediatric asthma . J Asthma 2017 ; 55:1–9.

Tang PC , Newcomb C . Informing patients: a guide for providing patient health information . J Am Med Inform Assoc 1998 ; 5 : 563 – 70 .

Neuberger M , Dontje K , Holzman G et al. Examination of office visit patient preferences for the after-visit summary (AVS) . Perspect Health Inf Manag 2014 ; 11 : 1d .

Pavlik V , Brown AE , Nash S , Gossey JT . Association of patient recall, satisfaction, and adherence to content of an electronic health record (EHR)-generated after visit summary: a randomized clinical trial . J Am Board Fam Med 2014 ; 27 : 209 – 18 .

Black H , Gonzalez R , Priolo C et al. True “meaningful use”: technology meets both patient and provider needs . Am J Manag Care 2015 ; 21 : e329 – 37 .

Emani S , Healey M , Ting DY et al. Awareness and use of the after-visit summary through a patient portal: evaluation of patient characteristics and an application of the theory of planned behavior . J Med Internet Res 2016 ; 18 : e77 .

Federman AD , Sanchez-Munoz A , Jandorf L et al. Patient and clinician perspectives on the outpatient after-visit summary: a qualitative study to inform improvements in visit summary design . J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016 ; 24 : e61 – 68 .

Belyeu BM , Klein JW , Reisch LM et al. Patients’ perceptions of their doctors’ notes and after-visit summaries: a mixed methods study of patients at safety-net clinics . Health Expect 2017 ; 21 : 485 – 93 .

Clarke MA , Moore JL , Steege LM et al. Toward a patient-centered ambulatory after-visit summary: identifying primary care patients’ information needs . Health Soc Care Community 2017 ; 43: 1 – 16 .

Emani S , Ting DY , Healey M et al. Physician perceptions and beliefs about generating and providing a clinical summary of the office visit . Appl Clin Inform 2015 ; 6 : 577 – 90 .

Anbar RD , Anbar JS , Hashim MA . Use of an after-visit summary to augment mental health of children and adolescents . Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2015 ; 54 : 1009 – 11 .

Dehen RI , Carter SU , Watanabe M . Impact of after visit summaries on patient return rates at an acupuncture and oriental medicine clinic . Med Acupunct 2014 ; 26 : 221 – 5 .

Jiggins K . A content analysis of the meaningful use clinical summary: do clinical summaries promote patient engagement ? Prim Health Care Res Dev 2016 ; 17 : 238 – 51 .

Koppel R , Lehmann CU . Implications of an emerging EHR monoculture for hospitals and healthcare systems . J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015 ; 22: 465–71.

Use the Teach-Back Method: Tool #5 . 2015 ; http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthlittoolkit2-tool5.html (accessed on 4 February 2018).

Ralston JD , Carrell D , Reid R et al. Patient web services integrated with a shared medical record: patient use and satisfaction . J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007 ; 14 : 798 – 806 .

Tieu L , Sarkar U , Schillinger D et al. Barriers and facilitators to online portal use among patients and caregivers in a safety net health care system: a qualitative study . J Med Internet Res 2015 ; 17 : e275 .

Ha Dinh TT , Bonner A , Clark R , Ramsbotham J , Hines S . The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: a systematic review . JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2016 ; 14 : 210 – 47 .

Wolff K , Cavanaugh K , Malone R et al. The diabetes literacy and numeracy education toolkit (DLNET): materials to facilitate diabetes education and management in patients with low literacy and numeracy skills . Diabetes Educ 2009 ; 35 : 233 – 45 .

White RO , Eden S , Wallston KA et al. Health communication, self-care, and treatment satisfaction among low-income diabetes patients in a public health setting . Patient Educ Couns 2015 ; 98 : 144 – 9 .

- primary health care

- electronic medical records

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2229

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Schedule a Demo

Learn more about textexpander from our experts., patient after visit summary template and examples.

The healthcare industry is increasingly focused on improving patient outcomes and enhancing communication between patients and healthcare providers. The patient after visit summary template is a critical component in ensuring patients’ continuity of care. Let's outline the components of a great summary template and review some examples in action.

Table of Contents

What is a Patient Visit Summary?

Importance of patient visit summary.

- Benefits of Using a Template

Patient Visit Summary Template and Examples

- 2 Example 1: Routine Check-Up

- 3 Example 2: Management of Chronic Diabetes

- 4 Example 3: Post-Operative Follow-Up

Type less. Say more.

Leave boring, repetitive copying & pasting in the past. Share text and images wherever you can type--so you can focus on what matters most.

(No credit card required)

A patient visit summary is a concise document generated after a clinical appointment or hospital visit. It summarizes the significant aspects of the visit, including diagnoses, treatments administered, medications prescribed, and follow-up care instructions. This document is designed to be an accessible and clear record for both the patient and any other healthcare providers who might need to review the patient’s recent medical history.

What makes a good visit summary?

A good patient visit summary is clear, concise, and free of medical jargon, making it easy for patients to understand. It should accurately reflect the details of the visit, provide clear instructions for care, highlight any changes in medication, and note any follow-up actions the patient needs to take.

A well-crafted visit summary aids in reducing miscommunication and potential errors, promoting safer and more effective care continuity. It empowers patients by making them informed participants in their healthcare processes, enhancing adherence to treatment plans and improving health outcomes.

Benefits of Using a Patient Visit Summary Template

Using a standardized patient visit summary template ensures consistency in the information provided across all patient interactions within a healthcare facility. It helps in maintaining completeness and accuracy in patient records, which is critical for quality care and legal compliance.

How TextExpander can help write better after visit summaries

Incorporating tools like TextExpander can significantly enhance the efficiency of creating patient visit summaries. TextExpander allows healthcare professionals to use predefined snippets to quickly insert common phrases and data fields, thus reducing typing errors and saving time.

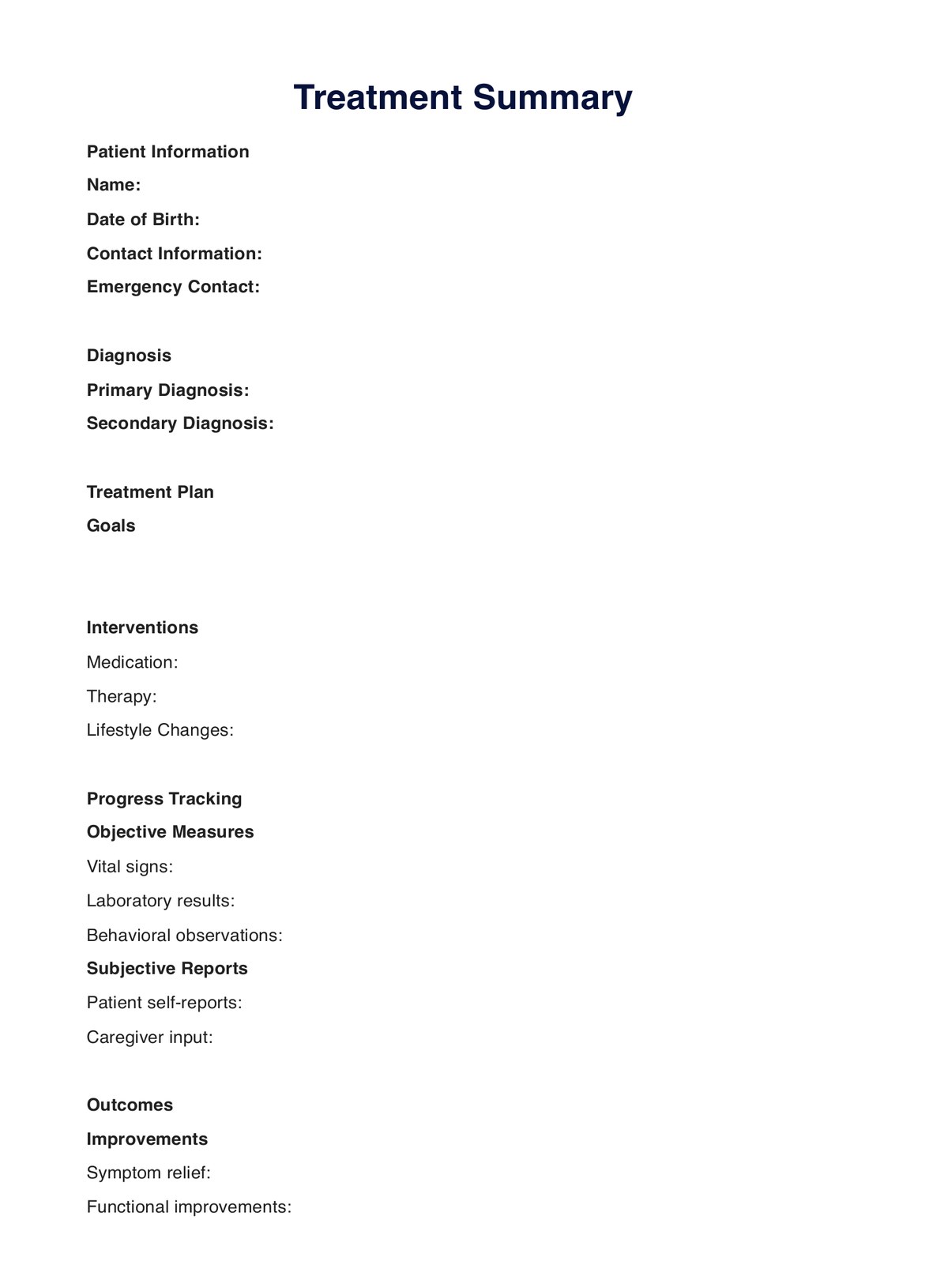

Patient After Visit Summary Template

Introduction: [Brief explanation of the document’s purpose.]

Patient Information: – Full name – date of birth – patient ID – visit date

Diagnoses: [List of diagnoses made during the visit.] Treatments: [Treatments administered during the visit.]

Medications Prescribed: [List of medications prescribed, including dosage and frequency.]

Follow-Up Instructions: [Specific instructions for follow-up, including scheduling next visits.]

Important Recommendations: [Lifestyle or dietary recommendations based on the patient’s current health status.]

Additional Notes: [Any other notes that may be relevant for the patient or subsequent healthcare providers.]

Conclusion: [Closing remarks, emphasizing any critical action points for the patient.]

Patient After Visit Summary Examples

Example 1: routine check-up.

Introduction: Summary of the routine check-up.

Patient Information: – Name: John Doe – DOB: 01/01/1980 – Patient ID: 123456 – Visit Date: 04/18/2024

Diagnoses: No new diagnoses.

Treatments: Routine physical examination performed.

Medications Prescribed: None.

Follow-Up Instructions: Annual physical scheduled for 04/18/2025.

Important Recommendations: Continue current exercise regimen.

Additional Notes: Flu vaccination offered and administered.

Conclusion: Review the exercise regimen in the next visit.

Example 2: Management of Chronic Diabetes

Introduction: Overview of diabetes management consultation.

Patient Information: – Name: Mary Smith – DOB: 05/23/1965 – Patient ID: 789101 – Visit Date: 04/18/2024.

Diagnoses: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.

Treatments: Review of blood sugar logs, adjustment of insulin therapy.

Medications Prescribed: Insulin glargine, 40 units at bedtime.

Follow-Up Instructions: Bi-weekly telehealth check-ins to monitor blood sugar levels.

Important Recommendations: Diet modifications to lower carbohydrate intake.

Additional Notes: Patient experiences hypoglycemia; advised to monitor symptoms closely.

Conclusion: Emphasize importance of adhering to new medication regimen.

Example 3: Post-Operative Follow-Up

Introduction: Summary of post-operative status following knee surgery.

Patient Information – Name: Lisa Green – DOB: 08/15/1987 – Patient ID: 654321 – Visit Date: 04/18/2024.

Diagnoses: Post-operative recovery from knee surgery.

Treatments: Wound check and removal of sutures.

Medications Prescribed: Ibuprofen 400 mg every 8 hours as needed for pain.

Follow-Up Instructions: Physical therapy twice a week for six weeks.

Important Recommendations: Avoid strenuous activities; focus on gentle knee exercises.

Additional Notes: Knee brace to be worn at all times except during physical therapy.

Conclusion: Next follow-up in two weeks to reassess progress.

What is TextExpander

With TextExpander, you can store and quickly expand full email templates, Slack messages, and more anywhere you type. That means no more misspellings, no need to memorize complex instructions, or type the same things over and over again. See for yourself here:

Not able to play the video? Click here to watch the video

Try it for yourself

With TextExpander, you can store and quickly expand full email templates, email addresses, and more anywhere you type. That means you’ll never have to misspell, memorize, or type the same things over and over again.

First, select a snippet you would like to try

Next, type this shortcut below: PVST1 PVST2 PVST3 PVST4

Stop typing the same thing over and over again.

With TextExpander, you can easily create custom snippets just like this.

Free for 30 days

Work smarter.

With TextExpander, you can store and quickly expand snippets anywhere you type. That means you'll never have to misspell, memorize, or type the same things over and over, ever again.

Related templates

Discharge summary template.

Discharge summaries are essential documents that ensure continuity of care from hospital to outpatient settings.

Nursing Admission Notes Template and Examples

Nursing admission notes are a critical aspect of patient care. Understanding how to effectively write these notes is crucial for nurses to ensure comprehensive and efficient patient care.

SOAP Notes Template and Examples

This article delves into what SOAP Notes are, their significance, who uses them, and provides specific examples across various specialties.

Less Repetition, More Customer Delight

TextExpander gives your team the power to do what they do best — faster.

Stop repetitive typing

With TextExpander, you can fly through repetitive tasks quickly by expanding the messages your team types regularly w/ just a few keystrokes.

- Create, share, and edit snippets of repetitive text

- Customize and optimize your snippets across teams

- Respond quickly and effectively from any platform

- Reduce burnout, onboard quickly, and ensure team alignment

(No credit card required / Free for 30 days)

- Start Free Trial

- Learning Center

- Getting Started

- Troubleshooting

- Public Groups

- Recruitment

- Customer Support

- Development

- About TextExpander

- Partner with TextExpander

© 2024 TextExpander, Inc. TextExpander is a registered trademark.

UI Health Care Epic Education

After visit summary (avs).

The After Visit Summary (AVS) is a report printed for the patient at the conclusion of every visit. It is meant to help patients better understand and remember what they have discussed with their treatment team. The AVS may include information on vitals, allergies, medication lists, orders, diagnoses, and upcoming appointments.

The following resources provide information on After Visit Summary functionality.

Adding Patient Instructions to the AVS - Clinical References - (Handout) The Patient Instructions activity allows you to add in depth information and patient instructions to the AVS quickly.

After Visit Summary: Last Dose - (Handout) The AVS now typically displays the last time a medication was given along with the Dosage, Indication (“Taking For…”), and Last Dose Comments. A clinician may need to manually add the last dose information for those that do not auto populate.

Use the Patient Station to Find the AVS from a Prior Encounter - (Handout) At the end of an IP (inpatient) or OP (outpatient) encounter, Epic creates a static copy of the After Visit Summary (AVS). To view the Static AVS from a prior encounter, use the Patient Station report pane as a shortcut.

Principal Problem and the After Visit Summary - (Handout) This document outlines the importance of identifying the principal problem (providers) for display on the AVS.

Return to Epic A-Z

A better after-visit summary

After-visit summaries are a mess. Some information is redundant, and some information is missing. Let's face it, does it matter if all your other doctors are on that sheet of paper? There has to be a better way. So Modern Healthcare set out to find it, asking around the industry to help create a summary that is useful for patients and providers alike. This is what we came up with. We want your help to make this after-visit summary even better. Submit your comments and critiques at the end of this article; we'll take those into account and create an updated version, which we'll publish soon. Download the PDF.

Our version of the form:

The experts weigh in:

Dr. Alex Federman, PROFESSOR, ICAHN SCHOOL OF MEDICINE: “What are the best practices for communicating information in print? Lots of white space, simple ideas expressed on a single line, no run-on sentences, information clearly grouped together.”

Dr. Eric Schneider: “If we thought about the visit as a co-planned use of time, the patient would say what they want to put on the list, the provider would say what they want to put on the list, and together they'd choose the most important.”

Federman: “We did some research with patients, and we learned that at the very top, they didn't want a crowded header—they wanted to know who their doctor is, who they saw, what number to call when they need something.”

TO DO LIST:

Schneider: “The No. 1 element is what the next steps are, whether that's changing a medication or making an appointment with somebody else or buying something from the drugstore. That should be front and center.”

Dr. Farzad Mostashari, CEO, ALEDADE: “It's important to have anticipatory guidance—if this happens, then do that.”

Federman: “People want actionable steps and concrete instructions.”

VITAL SIGNS:

Federman: “This kind of surprised us: People wanted to see their weight and their blood pressure.”

MEDICATION LIST:

Federman: “This is something that many of them do carry around with them, that they'll bring with them on a visit to a doctor. They wanted to see the brand and the generic names, and they wanted to see what the medication is for. ... Often you'll see a list of current meds and a separate list of meds to start and to stop. Patients find that very confusing.”

Send us a letter

Have an opinion about this story? Click here to submit a Letter to the Editor , and we may publish it in print.

Modern Healthcare A.M. Newsletter: Sign up to receive a comprehensive weekday morning newsletter designed for busy healthcare executives who need the latest and most important healthcare news and analysis.

- Current News

- Safety & Quality

- Digital Health

- Care Delivery

- Digital Edition (Web Version)

- Layoff Tracker

- Sponsored Content: Vital Signs Blog

- From the Editor

- Nominate/Eligibility

- 100 Most Influential People

- 50 Most Influential Clinical Executives

- 40 Under 40

- Best Places to Work in Healthcare

- Healthcare Marketing Impact Awards

- Innovators Awards

- Diversity Leaders

- Women Leaders

- Digital Health Summit

- Women Leaders in Healthcare Conference

- Leadership Symposium

- Health Equity Conference

- Workforce Summit

- Healthcare of the Future Conference

- Best Places to Work Awards Gala

- Diversity Leaders Gala

- - Future of Staffing

- - Health Equity & Environmental Sustainability

- - Hospital of the Future

- - Financial Resiliency

- - Value Based Care

- - Looking Ahead to 2025

- Podcast - Beyond the Byline

- Sponsored Podcast - Healthcare Insider

- Sponsored Video Series - One on One

- Sponsored Video Series - Checking In with Dan Peres

- Data & Insights Home

- Hospital Financials

- Staffing & Compensation

- Quality & Safety

- Mergers & Acquisitions

- Skilled Nursing Facilities

- Data Archive

- Resource Guide: By the Numbers

- Data Points

- Newsletters

- People on the Move

- Reprints & Licensing

- Sponsored Content

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Challenges optimizing the after visit summary

Alex federman.

a Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Erin Sarzynski

b Department of Family Medicine, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Cindy Brach

c Center for Delivery, Organization, and Markets, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, USA

Paul Francaviglia

d Epic Clinical Transformation Group, Information Technology Department, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, NY, USA

Jessica Jacques

Lina jandorf.

e Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Angela Sanchez Munoz

Michael wolf.

f Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Joseph Kannry

Authors’ contribution

Associated Data

Background:.

The after visit summary (AVS) is a paper or electronic document given to patients after a medical appointment, which is intended to summarize patients’ health and guide future care, including self-management tasks.

To describe experiences of health systems implementing a redesigned outpatient AVS in commercially available electronic health record (EHR) systems to inform future optimization.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with information technology and clinical leaders at 12 hospital and community-based healthcare institutions across the continental United States focusing on the process of AVS redesign and implementation. We also report our experience implementing a redesigned AVS in the Epic EHR at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, NY.

Health systems experienced many challenges implementing the redesigned AVS. While many IT leaders noted that the redesigned AVS is easier to understand and the document is better organized, they claim the effort is time-consuming, Epic system upgrades render AVS modifications non-functional, and primary care and specialty practices have different needs in regards to content and formatting. Our team was able to modify the document by changing the order of print groups, modifying the font size, bolding section headers, and inserting page breaks. Similar to other health systems, our team found that it is difficult to achieve some desired features due to limitations in the EHR platform.

Conclusion:

Health IT leaders view the AVS as a valuable source of information for patients. However, limitations to AVS modifications in EHR systems present challenges to optimizing the tool. EHR vendors should incorporate learning from healthcare systems innovation efforts and consider building more flexibility into their product development.

1. Introduction

The after visit summary (AVS) is given to patients after medical appointments to summarize their health and guide future care. If properly designed, the AVS can be an educational tool to facilitate patients’ understanding of their health, reduce recall problems, and encourage adherence to self-management tasks [ 1 – 9 ].

The AVS is nearly universal in the United States, resulting from incentives to promote the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs). Meaningful Use requirements mandated provision of an AVS and specified required elements [ 10 ]. However, patients infrequently reference, use, or even retain their AVS, suggesting currently designed documents do not meeting patients’ needs [ 11 ]. Since Meaningful Use dropped the requirement of providing an AVS in 2016, health care systems have been free to redesign their AVS as they choose to optimize its usefulness for patients.

The purpose of this paper is to provide information that may facilitate the work of health systems seeking to improve or modify their outpatient AVS. We do so by reporting the results of qualitative interviews with health information technology (IT) leaders from across the US who worked on AVS customization at their institutions, and by providing a narrative report of our experience implementing a redesigned, patient-centered AVS within the Epic EHR at the Mount Sinai Hospital.

2. Materials and methods

All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University.

2.1. Semi-Structured interviews with health IT experts

To provide implementation insights, we conducted a qualitative study comprised of semi-structured interviews with 12 health IT experts from clinical settings to elicit their experiences with AVS improvement and implementation. Qualitative methods followed standard procedures of data collection and analysis as described by Patton [ 12 ]. We conducted convenience sampling by identifying key informants through an announcement on the American Medical Informatics Association Epic Users’ listserv, which asked individuals having experience with AVS modification to contact us to share their insights. Additionally, we contacted individuals known to the investigators to have been involved in such work. Thereafter, we identified other individuals by snowball sampling, and purposively contacted potential participants to achieve geographic and practice setting variation [ 12 ]. Once we contacted a potential interviewee, we stated the purpose of the interview and confirmed whether the individual played a central role in redesigning and implementing changes to the AVS. If the person was not, we asked her/him to identify the appropriate contact.

One investigator (AF) conducted all interviews, each lasting 20–30 minutes, using an interview guide ( Appendix A ). Interview topics included practice workflow, institutional AVS modifications, and facilitators and barriers to AVS implementation. Interview notes were taken and independently reviewed by two investigators for themes and sub-themes, using logical analysis [ 12 ]. The two investigators then compared and reconciled their coding. Subsequent interviews were conducted until no new themes emerged.

2.2. AVS optimization

Independent of our interviews with IT leaders, we used a four step process to redesign and implement the AVS for primary care practices at Mount Sinai Hospital: 1) identify patients’ and clinicians’ preferred content, formatting, and order; 2) draft an AVS “mock-up” in Microsoft Word ( Appendix B ); 3) refine the AVS mock-ups with patient feedback; and 4) modify the AVS in Mount Sinai’s Epic EHR (version 2014) to resemble the redesigned AVS mock-up as closely as possible ( Appendix C ). We report Step 1 results elsewhere [ 13 ]. The remaining steps follow.

2.2.1. Create AVS mock-ups

We applied results of our prior research to create AVS mock-ups by prioritizing specific content, organization/formatting, and understandability features [ 13 , 14 ]. We developed four mock-ups differing by format elements, including order of content, use of page breaks, differing styles of presenting medication data, and variations in font size. The mock-ups accounted for known technical challenges in modifying the Epic AVS and health literacy design principles to ensure clear and effective print communication, as specified in the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and similar resources ( Table 1 ) [ 15 – 17 ]. Additionally, we applied the Social Cognitive-Self-Efficacy theory to promote self-management behaviors by presenting only relevant, easy to follow information [ 18 ].

Theoretical and Empirical Underpinnings of AVS Optimal Design.

2.2.2. Refine AVS mock-ups

We conducted cognitive interviews with patients to obtain feedback on mock-ups and refine their design. We recruited patients from the outpatient primary care practice of the Mount Sinai Hospital, which serves adults from predominantly low-income communities of upper Manhattan and the South Bronx. Investigators used a think-aloud procedure to identify patients’ perceptions of AVS documents and their understanding of content [ 29 ]. At the end of the interview, we asked patients to select a preferred document. We continued this process with iterative refinement of mock-ups using patient feedback (iterative user-centered design) [ 30 ]. The AVS was considered redesigned when the majority of patients single mock-up.

2.3. Implementation

To implement our redesigned AVS, we held extensive discussions with members of the Mount Sinai Epic EHR team to ensure maximal use of all possible EHR functionality to support customization. Additionally, the team spoke frequently with the vendor for additional technical support. Over the course of several conference calls, email exchanges, and one in-person meeting between Epic technical support and Mount Sinai AVS development staff, members of the research team (JK, JJ, PF) identified ways to implement the redesigned AVS in Epic (version 2014) as closely as possible.

3.1. Semi-structured interviews with health IT experts

We interviewed health care IT leaders from 12 institutions in eight states. Five were academic medical centers, four were non-academic medical centers, two were outpatient clinical networks, and one was a federally qualified health center. These institutions used the Epic (n = 7), NextGen (n = 2), Vista (n = 2), and eClinical Works (n = 1) EHR platforms. Interviewees were seven chief health informatics officers, one electronic health record “champion,” one quality improvement director, one chief medical officer, one clinical investigator, and one primary care-focused division chief. These individuals participated in AVS improvement efforts directly or closely with key personnel. All participants reported the motivation of their respective AVS development committees was to improve the document because it was a sub-optimal patient education tool and represented their institution poorly. Most believed their patients did not use the AVS and felt physicians in their practices thought the AVS had little value for their patients. However, they said their redesigned AVSs were more organized and easier to understand than the standard AVS generated by their EHR.