1964 Tour de France

51st edition: june 22 - july 14, 1964, results, stages with running gc, photos and history.

1963 Tour | 1965 Tour | Tour de France database | 1964 Tour Quick Facts | Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1964 Tour de France

Map of the 1964 Tour de France

The Golden Sayings of Epictetus is available as an audiobook here .

1964 Tour Quick Facts:

4,502.4 km raced at an average speed of 35.420 km/hr.

There were 132 starters and 81 classified finishers.

The 1964 Tour de France was one of the greatest races of all time.

Anquetil had come off his Giro victory that ended just fourteen days before the Tour started and was tired.

His battle with Poulidor culminating in a titanic side-by side climb up Puy de Dôme in stage 20, where Anquetil had conserved just 14 seconds of his lead, is one of the legends of the sport.

Although Anquetil was now the first 5-time Tour winner and the second winner of the Giro-Tour double (after Coppi).

He would never again win a Grand Tour.

Complete Final 1964 Tour de France General Classification:

- Raymond Poulidor (Mercier-BP) @ 55sec

- Federico Bahamontes (Margnat-Paloma) @ 4min 44sec

- Henry Anglade (Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune) @ 6min 42sec

- Georges Groussard (Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune) @ 10min 34sec

- André Foucher (Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune) @ 10min 36sec

- Julio Jiménez (KAS) @ 12min 13sec

- Gilbert Desmet (Wiels-Groene-Leeuw) @ 12min 17sec

- Jans Junkermann (Wiels-Groene-Leeuw) @ 14min 2sec

- Vittorio Adorni (Salvarani) @ 14min 19sec

- Esteban Martin (Margnat-Paloma) @ 25min 11sec

- Fernando Manzaneque (Ferrys) @ 32min 9sec

- Francisco Gabica (KAS) @ 41min 47sec

- Tom Simpson (Peugeot-BP) @ 41min 50sec

- Rudi Altig (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 42min 8sec

- Karl-Heinz Kunde (Wiels-Groene-Leeuw) @ 42min 16sec

- Joaquin Galera (KAS) @ 43min 47sec

- Henri Duez (Peugeot-BP) @ 46min 16sec

- Joseph Novales (Margnat-Paloma) @ 48min 49sec

- Eddy Pauwels (Margnat-Paloma) @ 50min 2sec

- Arnaldo Pambiano (Salvarani) @ 52min 0sec

- Louis Rostollan (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 55min 6sec

- Sebastian Elorza (KAS) @ 55min 14sec

- Jan Janssen (Pelforth) @ 59min 31sec

- Battista Babini (Salvarani) @ 1hr 5min 24sec

- Rogelio Hernandez (Ferrys) @ 1hr 8min 16sec

- Claude Mattio (Margnat-Paloma) @ 1hr 13min 45sec

- Raymond Mastrotto (Peugeot-BP) @ 1hr 16min 34sec

- Paul Vermeulen (Mercier-BP) @ 1hr 18min 50sec

- Willy Monty (Pelforth) @ 1hr 23min 26sec

- Jean Gainche (Mercier-BP) @ 1hr 28min 20sec

- Victor Van Schil (Mercier-BP) @ 1hr 30min 13sec

- Edouard Sels (Solo-Superia) @ 1hr 31min 35sec

- Guy Epaud (Pelforth) @ 1hr 33min 12sec

- Jean Stablinski (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 1hr 34min 10sec

- André Zimmerman (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 1hr 37min 52sec

- Hubertus Zilverberg (Flandria-Romeo) @ 1hr 41min 30sec

- Albertus Geldermans (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 1hr 46min 24sec

- Cees Haast (Televizier) @ 1hr 47min 44sec

- Gilbert Desmet (Wiels-Groene Leeuw) @ 1hr 48min 12sec

- Juan Uribezubia (KAS) @ 1hr 49min 33sec

- Camille Vyncke (Flandria-Romeo) @ 2hr 0min 17sec

- Jo De Roo (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 2hr 0min 23sec

- Luis Otano (Ferrys) @ 2hr 1min 11sec

- José Segu (Margnat-Paloma) @ 2hr 1min 34sec

- Antonio Franchi (Salvarani) @ 2hr 3min 28sec

- Robert Poulot (Mercier-BP) @ 2hr 6min 26sec

- Bruno Fantinato (Salvarani) @ 2hr 6min 35sec

- Benoni Beheyt (Wiels-Groene Leeuw) @ 2hr 8min 7sec

- Italo Mazzacurati (Savarani) @ 2hr 8min 8sec

- Edouard Delberghe (Pelforth) @ 2hr 9min 40sec

- Martín Piñera (KAS) @ 2hr 11min 3sec

- Guillaume Van Tongerloo (Flandria-Romeo) @ 2hr 15min 34sec

- Hubert Ferrer (Pelforth) @ 2hr 15min 59sec

- Antonio Bertran (Ferrys) @ 2hr 18min 38sec

- Michael Wright (Wiels-Groene Leeuw) @ 2hr 19min 8sec

- Bernard Vendekerkhove (Solo-Superia) @ 2hr 21min 29sec

- Michel Van Aerde (Solo-Superia) @ 2hr 21min 57sec

- Robert Cazala (Mercier-BP) @ 2hr 24min 21sec

- Jo De Haan (Televizier) @ 2hr 25min 47sec

- Edgard Sorgeloos (Solo-Superia) @ 2hr 30min 22sec

- Mario Minieri (Salvarani) @ 2hr 31min 29sec

- Pierre Everaert (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 2hr 32min 9sec

- Rik Wauters (Televizier) @ 2hr 34min 6sec

- Barry Hoban (Mercier-BP) @ 2hr 38min 48sec

- Hank Nijdam (Televizier) @ 2hr 41min 2sec

- André Darrigade (Margnat-Paloma) @ 2hr 41min 9sec

- Willy Berboven (Solo-Superia) @ 2hr 42min 9sec

- Camille Le Menn (Peugeot) @ 2hr 47min 36sec

- Frans Brands (Flandria-Romeo) @ 2hr 48min 28sec

- François Hamon (Peugeot-BP) @ 2hr 50min 23sec

- Vic Denson (Solo-Superia) @ 2hr 57min 23sec

- Antonio Barrutia (KAS) @ 2hr 57min 57sec

- Joseph Groussard (Pelforth) @ 2hr 59min 28sec

- Frans Aerenhouts (Mercier-BP) @ 3hr 3min 6sec

- Jean Grazcyk (Margnat-Paloma) @ 3hr 4min 21sec

- Jean Milesi (Margnat-Paloma) @ 3hr 7min 7sec

- Jean-Pierre Genet (Mercier-BP) @ 3he 12min 55sec

- Jean-Baptiste Claes (Wiels-Groene Leeuw) @ 3hr 12min 57sec

- Salvador Honrubia (Ferrys) @ 3hr 17min 7sec

- Anatole Novak (St Raphaël-Gitane) @ 3hr 19min 2sec

Climbers' Competition:

- Julio Jiménez (KAS): 167

- Raymond Poulidor (Mercier-BP): 90

- Hans Junkermann (Wiels-Groene Leeuw): 47

- Henry Anglade (Pelforth): 44

- Jacques Anquetil (St Raphaël-Gitane): 34

- André Foucher (Pelforth): 33

- Karl-Heinz Kunde (Wiels-Groene Leeuw): 27

- Vittorio Adorni (Salvarani): 26

- Martín Piñera (KAS): 23

Points Competition:

- Edward Sels (Solo Superia): 199

- Rudi Altig (St. Raphaël-Gitane): 165

- Gilbert Desmet (Wiels-Groene Leeuw): 147

- Raymond Poulidor (Mercier-BP): 133

- Jacques Anquetil (St Raphaël-Gitane): 111

- Benoni Beheyt (Wiels-Groene Leeuw), Henk Nijdam (Televizier): 103

- Vittorio Adorni (Salvarani): 83

- André Darrigade (Margnat-Paloma): 78

Team Classification:

- Pelforth: 381hr 33min 36sec

- Wiels-Groene leeuw @ 30min 24sec

- St Raphaël-Gitane @ 30min 52sec

- Margnat-Paloma @ 53min 9sec

- KAS @ 1hr 7min 34sec

- Salvarani @ 1hr 50min 42sxec

- Mercier-BP @ 2hr 2min 53sec

- Ferrys @ 2hr 11min 22sec

- Peugeot-BP @ 2hr 27min 35sec

- Flandria-Romeo @ 4hr 32min 17sec

- Solo-Superia @ 4hr 39m 5sec

- Televizier @ 5hr 35min 10sec

Content continues below the ads

Stage Results with Running GC:

Stage 1: Monday, June 22, Rennes - Lisieux, 215 km

- Edward Sels: 5hr 14min 57sec

- Michael Wright s.t.

- Benoni Beheyt s.t.

- Willy Bocklant s.t.

- Rudi Altig s.t.

- Jo De Roo s.t.

- Jan Janssen s.t.

- Jean Graczyk s.t.

- Frans Melckenbeeck s.t.

- Emile Daems s.t.

GC after stage 1:

- Edward Sels: 5hr 13min 57sec

- Michael Wright @ 30sec

- Benoni Beheyt @ 1min

Stage 2: Tuesday, June 23, Lisieux - Amiens, 208 km

- André Darrigade: 5hr 7min 47sec

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- André Van Aert s.t.

- Frans Verbeeck s.t.

- Gilbert Desmet s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Edward Sels: 10hr 21min 44sec

- André Darrigade s.t.

- Jan Janssen @ 30sec

- Willy Bocklant @ 1min

Stage 3A: Wednesday, June 24, Amiens - Forest, 196.5 km

- Bernard Vanderkerkhove: 5hr 7min 32sec

- Jean Stablinski s.t.

- Gilbert Desmet @ 3sec

- Jean Anastasi @ 5sec

- Edward Sels @ 19sec

- Arthur De Cabooter s.t.

GC after stage 3A:

- Bernard Vanderkerhove: 15hr 29min 16sec

- Jan Janssen @ 49sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 1min 3sec

- Willy Bocklant @ 1min 19sec

Stage 3B: Wednesday, June 24, Forest 21.3 km Team Time Trial.

The rider's real times were applied to their GCs. Team times were caculated by adding up each teams' first three riders' times.

- KAS-Kaskol: 1hr 34min 5sec

- Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune @ 8sec

- Wiel's-Groene-Leeuw @ 21sec

- Solo-Superia @ 43sec

- Ferrys @ 1min 17sec

- Mercier-BP @ 1min 25sec

- Peugeot-BP @ 1min 37sec

- St. Raphaël-Gitane @ 1min 43sec

- Salvarani @ 2min 41sec

- Margnat-Paloma @ 3min 49sec

- Flandria-Romeo @ 4min 52sec

- Televizier @ 5min 17sec

GC after stage 3B:

- Bernard Vanderkerkhove: 16hr 52sec

- Jan Janssen @ 39sec

- Michael Wright @ 42sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 55sec

- José-Antonio Momene @ 1min 4sec

- Francisco Gabica s.t.

- Henry Anglade s.t.

- Carlos Echevarria @ 1min 6sec

- François Mahé @ 1min 9sec

Stage 4: Thursday, June 25, Forest - Metz, 291.5 km

- Rudi Altig: 8hr 26min

- Henk Nijdam s.t.

- Armand Desmet s.t.

- Fernando Manzaneque s.t.

- Edward Sels @ 8sec

- Frans Aerenhouts s.t.

GC after stage 4:

- Bernard Vanderkerkhove: 24hr 27min

- Rudi Altig @ 31sec

- Henry Anglade @ 56sec

Stage 5: Friday, June 26, Metz - Fribourg

- Willy Derboven: 4hr 2min 51sec

- Joaquin Galera s.t.

- Joseph Groussard s.t.

- Georges Groussard s.t.

- Edward Sels @ 4min 2sec

GC after Stage 5:

- Rudi Altig: 28hr 29min 52sec

- Georges Groussard @ 1min 8sec

- Joaquin Galera @ 1min 29sec

- Joseph Groussard @ 3min 25sec

- Bernard Vanderkerhove @ 4min 1sec

- Edward Sels @ 4min 20sec

- Jan Janssen @ 4min 32sec

- Michael Wright @ 4min 43sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 4min 56sec

- Henry Anglade @ 4min 57sec

Stage 6: Saturday, June 27, Fribourg - Besançon, 200 km

- Henk Nijdam: 5hr 5min 18sec

- Jo De Haan @ 11sec

- Edward Sels s.t.

- Bruno Fantinato s.t.

- Rik Wouters s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Rudi Altig: 33hr 35min 21sec

- Bernard Vanderkerkhove @ 4min 1sec

Stage 7: Sunday, June 28, Champagnole - Thonon les Bains, 195 km.

- Jan Janssen: 5hr 2min 14sec

- Vin Denson s.t.

- Henri Duez s.t.

- Jos Hoevenaers s.t.

- Eddy Pauwels s.t.

- Arnoldo Pambianco s.t.

- Raymond Poulidor s.t.

- Hans Junkermann s.t.

- Guy Epaud s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Rudi Altig: 38hr 38min 9sec

- Georges Groussard @ 34sec

- Jan Janssen @ 2min 58sec

- Bernard Vandekerkhove @ 4min 1sec

- Sebastian Elorza @ 4min 37sec

- André Foucher @ 4min 42sec

Stage 8: Monday, June 29, Thonon les Bains - Briançon, 248.5 km

- Federico Bahamontes: 7hr 20min 52sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 1min 32sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 1min 33sec

- André Foucher s.t.

- Jean-Claude Lebaube @ 1min 36sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1min 49sec

- Esteban Martin @ 2min 18sec

- Tom Simpson @ 2min 39sec

GC after Stage 8:

- Georges Groussard: 46hr 1min 8sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 3min 35sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 4min 7sec

- André Foucher @ 4min 8sec

- Henry Anglade @ 4min 23sec

- Rudi Altig @ 4min 38sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 4min 47sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 5min 22sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 6min 3sec

- Tom Simpson @ 6min 10sec

Stage 9: Tuesday, June 30, Briançon - Monaco, 239 km

- Jacques Anquetil: 7hr 26min 59sec

- Tom Simpson s.t.

- Vittorio Adorni s.t.

- Claude Mattio s.t.

- Battista Babini s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Georges Groussard: 53hr 28min 7sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 22sec

- Henri Anglade @ 4min 23sec

- Tom Simpson @ 5min 40sec

- Jean-Claude Lebaube @ 6min 17sec

- Esteban Martin @ 6min 53sec

Stage 10A: Wendesday, July 1, Monaco - Hyères, 187.5 km

- Jan Janssen: 5hr 30min 58sec

- Jean-Pierre Genet s.t.

- Guillaume Van Tongerloo @ 4sec

- Edward Sels @ 1min 2sec

GC after Stage 10A:

- Georges Groussard: 59hr 7sec

- Rudi Altig @ 6min 9sec

Stage 10B: Wednesday, July 1, Hyères - Toulon 20.8 km Individual Time Trial

- Jacques Anquetil: 27min 52sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 36sec

- Rudi Altig @ 54sec

- Ferdi Bracke @ 1min 7sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 31sec

- Henry Anglade @ 1min 33sec

- Henk Nijdam @ 1min 36sec

- Francisco Gabica @ 1min 44sec

- Miguel Pacheco @ 1min 50sec

- Albertus Geldermans @ 1min 57sec

GC after Stage 10B:

- Georges Groussard: 59hr 30min 50sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1min 11sec

- Raymond poulidor @ 1min 42sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 3min 4sec

- Henry Anglade @ 3min 5sec

- Rudi Altig @ 4min 12sec

- André Foucher @ 4min 16sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 5min 16sec

- Tom Simpson @ 5min 29sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 6min 3sec

Stage 11: Thursday, July 2, Toulon - Montpellier, 250 km

- Edward Sels: 7hr 49min 28sec

- Jan Graczyk s.t.

- Jo De Haan s.t.

- Antonio Barrutia s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Georges Groussard: 67hr 20min 23sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 1min 42sec

- Rudi Altig @ 4min 7sec

- Tom Simpson @ 5min 24sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 5min 58sec

Stage 12: Friday, July 3, Montpellier - Perpignan, 174 km.

- Jo De Roo: 4hr 44min 20sec

- Guy Epaud @ 1sec

- Henk Nijdam @ 3sec

- Mario Minieri @ 3sec

- Barry Hoban @ 6sec

- José Segu s.t.

GCafter Stage 12:

- Georges Groussard: 72hr 4min 56sec

- Rudi Altig @ 4min

Stage 13: Saturday, July 4, Perpignan - Andorra, 170 km

- Julio Jiménez: 4hr 54min 53sec

- Benoni Beheyt @ 8min 52sec

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Sebastian Elorza s.t.

GC after stage 13:

- Georges Groussard: 77hr 8min 41sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 3min 11sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 5min 3sec

Stage 14: Monday, July 6, Andorra - Toulouse, 186 km

- Edward Sels: 4hr 36min 56sec

- Luis Otano s.t.

- Willy Monty s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Georges Groussard: 81hr 45min 37sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1min 26sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 4min 28sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 5min 28sec

- Rudi Altig @ 6min 36sec

Stage 15: Tuesday, July 7, Toulouse - Luchon, 203 km

- Raymond Poulidor: 6hr 7min 55sec

- Francisco Gabica @ 1min 9sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 1min 43sec

GC after stage 15:

- Georges Groussard: 87hr 55min 15sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 1min 35sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 3min 29sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 5min 21sec

- Tom Simpson @ 8min 17sec

Stage 16: Wednesday, July 8, Luchon - Pau, 197 km

- Federico Bahamontes: 6hr 18min 47sec

- Jan Janssen @ 1min 54sec

- Karl-Heinz Kunde s.t.

- Esteban Martin

GC after Stage 16:

- Georges Groussard : 94hr 15min 56sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 35sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 11min 13sec

Stage 17: Thursday, July 9, Peyrehorade - Bayonne 42.6 km Individual Time Trial

- Jacques Anquetil: 1hr 1min 53sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 37sec

- Rudi Altig @ 1min 19sec

- Henry Anglade @ 2min 2sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 2min 43sec

- Francisco Gabica @ 2min 44sec

- Camille Le Menn @ 2min 55sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 3min 24sec

- Albertus Geldermans @ 3min 41sec

- Barry Hoban @ 3min 51sec

GC after Stage 17:

- Jacques Anquetil: 95hr 18min 55sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 56sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 3min 31sec

- Henry Anglade @ 4min 1sec

- Georges Groussard @ 4min 53sec

- André Foucher @ 7min 30sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 7min 46sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 9min 2sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 11min 10sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 12min 50sec

Stage 18: Friday, July 10, Bayonne - Bordeaux, 187 km

- André Darrigade: 5hr 5min 12sec

- Barry Hoban s.t.

- Michel Van Aerde s.t.

- Edgar Sorgeloos s.t.

- Mario Minieri s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Jacques Anquetil: 100hr 24min 7sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 7min 43sec

Stage 19: Saturday, July 11, Bordeaux - Brive, 215.5 km

- Edward Sels: 5hr 50min 30sec

- Mario Minieri @ 1sec

- Frans Aerenhouts @ 2sec

- Henk Nijdam @ 4sec

- Jean Gainche s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Jacques Anquetil: 106hr 14min 41sec

Stage 20: Sunday, July 12, Brive - Puy de Dôme, 237.5 km

Major ascents: St. Privat, Puy de Dôme

- Julio Jiménez: 7hr 9min 33sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 11sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 57sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 30sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1min 39sec

- Henry Anglade @ 1min 59sec

- André Foucher @ 2min 4sec

- Francisco Gabica @ 2min 32sec

- Fernando Manzaneque @ 2min 46sec

- Jan Janssen @ 3min 22sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Jacques Anquetil: 113hr 25min 53sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 14sec

- Federico Bahamontes @ 1min 33sec

- Henry Anglade @ 4min 21sec

- Georges Groussard @ 6min 49sec

- André Foucher @ 7min55sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 8min 31sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 10min 25sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 10min 49sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 14min 41sec

Stage 21: Monday, July 13, Clermont Ferrand - Orléans, 311 km

- Jean Stablinski: 9hr 29min 33sec

- Battista Babini @ 1sec

- Hubert Ferrer s.t.

- Joseph Novales s.t.

- Salvador Honrubia s.t.

- Edward Sels @ 9min 37sec

- Benoni Beheyt

GC after Stage 21:

- Jacques Anquetil: 123hr 5min 3sec

- André Foucher @ 7min 55sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 12min 41sec

Stage 22A: Tuesday, July 14, Orléans - Versailles, 118.5 km

- Benoni Beheyt: 3hr 25min 24sec

- Edward Sels @ 7sec

- Victor Van Schil s.t.

GC after stage 22A:

- Jacques Anquetil: 126hr 32min 54sec

- Raymond poulidor @ 14sec

Stage 22B (final stage): Tuesday, July 14, Versailles - Paris 27.5 km Individual Time Trial

- Jacques Anquetil: 37min 10sec

- Rudi Altig @ 15sec

- Raymond Poulidor @ 21sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 18sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 1min 32sec

- Henry Anglade @ 2min 1sec

- Albertus Geldermans @ 2min 6sec

- Camille Le Menn @ 2min 15sec

- André Foucher @ 2mn 21sec

Complete Final 1964 Tour de France General Classification

The Story of the 1964 Tour de France:

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Tour de France", Volume 1. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book in either print, eBook or audiobook formats. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

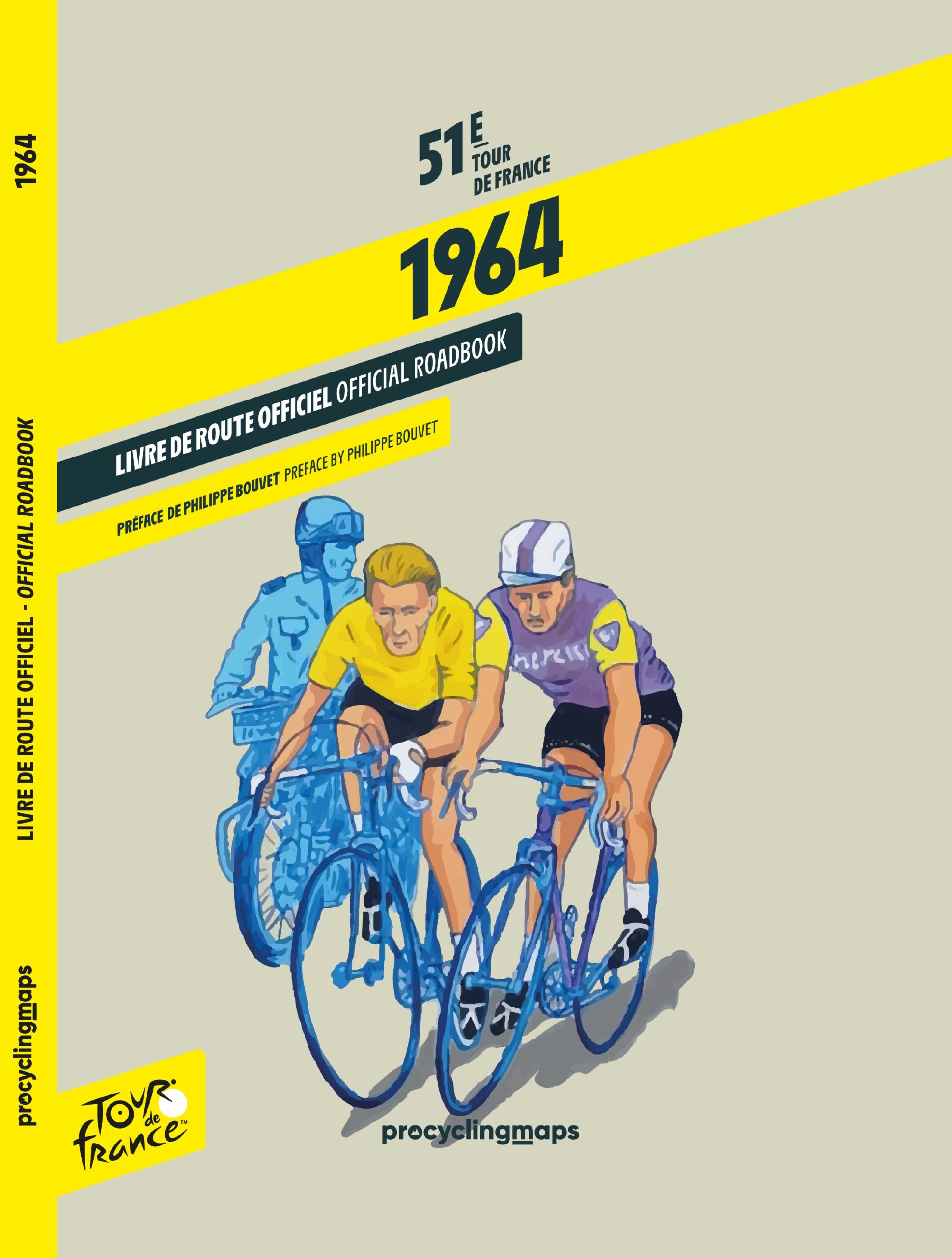

Anquetil started the 1964 season well. He won Ghent-Wevelgem and then the Giro d'Italia. If he won the 1964 Tour he would achieve the Giro-Tour double, a feat previously accomplished in the same year only by Fausto Coppi. He would also perform the then-unequaled feat of winning the Tour de France for a fifth time.

He had taken the 1964 Giro lead in the stage 5 time trial and had held the leader's Pink Jersey for the rest of the race. Subjected to relentless attacks, he was forced to work especially hard to defend his lead in the Giro. The effort left him exhausted. Many wondered if Anquetil could ride an effective Tour that started just 2 weeks after this brutal Giro ended. Anquetil was aiming for the stars. While his 4 Tour wins were the record, a fifth win while doing a Giro-Tour double would make him one of the greatest racers in history.

There were no new challengers on the Tour scene so the main contenders for the 1964 Tour were the same as the year before, Bahamontes and Poulidor.

Poulidor brought excellent form to the 1964 Tour. He won the 1964 Vuelta a España, which was then run early in the year, as well as the Critérium National. He was second at Milan–San Remo and the Dauphiné Libéré and fourth in Paris-Nice. He had every right to expect that he would do well and possibly even win the Tour.

Let's stop a minute and take a look at Raymond Poulidor.

The battles between Poulidor and Anquetil enlivened racing (and arguments between racing fans) as much in France as the Bartali-Coppi contests fired up the Italians a generation before. Poulidor was the superior climber and Anquetil was the better time trialist. Poulidor was never able to gain enough of an advantage in the mountains to make up for his losses against the clock. Anquetil was also the superior tactician and psychologist. When his physical limits threatened his chances he could call upon his superior intellect and salvage a race. This was a gift denied Poulidor.

Here is Pouildor's Tour Record:

By the years:

Here's a selection of other Poulidor wins: Milan–San Remo, Fleche Wallonne, Grand Prix des Nations (even though he wasn't a time trialist of Anquetil's caliber, he was still very, very good against the clock), Vuelta a España, Critérium National, Dauphiné Libéré, Catalonian Week and Paris–Nice.

In 1974, at the Montreal World Road Championships, only 39-year old Raymond Poulidor could stay with Eddy Merckx when he attacked on the last time up Mount Royal, finishing just 2 seconds behind the great man. If anyone could paraphrase Raphaël Géminiani this time, it was Poulidor. He was first because he was the first human across the line. No normal person was going to beat Merckx that day.

This was an extraordinary career by any measure.

In the wars for the affection of the French people, Poulidor won hands down. It baffled and angered Anquetil that even though Anquetil could beat Poulidor over and over again, "Pou-Pou", the "Eternal Second" was first in the French hearts and remains there today. I have often thought that Poulidor tapped into a piece of the French psyche that made Crecy and Agincourt possible. It was at Crecy, France that the English with their technically superior longbows slaughtered the French armored knights. Later, at Agincourt, the French knights jostled for position to be first to hurl themselves against the English longbowmen only to be slaughtered again. Le Gloire (glorious renown) isn't necessarily gained by victory.

To continue:

The 1964 Tour was 4,504 kilometers divided into 25 stages going clockwise, Alps first then the Pyrenees. To increase the drama the Tour would head into the Massif Central and climb the Puy de Dôme, an extinct volcano whose final 5 kilometers have a gradient that approaches 13%.

For the first part of the Tour as the race sped east from Rennes in Brittany, Anquetil was unremarkable. He knew he had a finite supply of energy and had announced in advance his plans to let others do the racing in the first week. He didn't even place in the top 10 of a stage until stage 8.

His teammate Rudi Altig, however, did have early ambitions. After passing through Brittany and Normandy, the Tour headed into Belgium and then southeast into Germany. Altig wanted to be wearing the leader's jersey while the Tour went through his home country. By winning the fourth stage into Metz he was in an excellent position to realize his ambition. He had the Green Points Jersey and was only 31 seconds behind the current leader, Bernard van de Kerckhove.

The next stage traveled through the Vosges, hilly country in eastern France that encouraged breakaways. Altig powered a 5-man break 4 minutes clear of the field into Fribourg and secured the overall lead. Rudi Altig the German rider was in Yellow in Germany. Anquetil was not entirely pleased that his teammate had been so successful. In that break was a rider on the Pelforth team, Georges Groussard, who was now in second place, only a minute behind Altig. Groussard was an excellent rider with fine climbing skills and Altig had given him a 4-minute boost. Anquetil did not relish the prospect of overcoming that time gain just so that Altig could enjoy a little bit of German glory.

Stage 7 went through the Jura, mountains on the northeastern edge of the Alps. Tongues wagged when Poulidor got into a 15-man break that included Groussard and left the rest of the peloton (with Anquetil) a half-minute behind. Altig was still in Yellow but Poulidor had stolen a march on a very obviously tired Anquetil.

Stage 8 was the first full-blown Alpine stage with both the Télégraphe and the Galibier. Bahamontes was first over both summits. Poulidor went after him on the Galibier and came close to making contact with the flying Spaniard. Meanwhile, Anquetil was suffering, losing time on the climb. Once over the top he used his considerable descending skills to try to close the gap. Even with a flat tire he was still able to limit his losses to Poulidor to only 17 seconds. Bahamontes won the stage, Poulidor came in second and thereby gained a 3 second time bonus. Anquetil's worries about Groussard turned out to be completely justified. The Pelforth rider was now in Yellow.

So, after the first day of hard climbing here were the standings:

Anquetil showed he was up for the race the next day in the Briançon-Monaco stage which took in 3 major climbs. None of the contenders was able to get away from the others, and 22 riders came into Monaco, driven hard by an Anquetil who had miraculously found incredible stores of energy. It was a track finish Poulidor should have won, but he sprinted too early, not realizing that there was another lap to ride. Anquetil beat Tom Simpson for the stage. Poulidor's missing (and Anquetil's winning) the time bonus for winning the stage would loom very large at the end of the Tour. Anquetil was now in fifth place, 4 minutes, 22 seconds behind Groussard.

Stage 10b was a 20.8-kilometer time trial and Anquetil won it with Poulidor just 36 seconds behind.

Anquetil was relentlessly hunting Groussard and getting closer by the day. The General Classification after the 10b time trial:

By the time the Tour came to its rest day in Andorra in the Pyrenees, the only significant change in General Classification was that Bahamontes had dropped to fifth. Good Grand Tour riders always go for a ride on the rest day. The body has become habituated to cycling and a day completely off the bike makes it very difficult to start the next day, the rider's legs are "blocky" and devoid of power. Poulidor and the others dutifully gave their bodies the exercise they needed. Everyone but Anquetil, that is. Jacques liked to enjoy life. He went to a picnic and enjoyed himself on big portions of barbecued lamb and as usual, drank heartily. His director, Raphaël Géminiani, was there and apparently encouraged the drinking.

At the start of the Tour a psychic had predicted that Anquetil would abandon on the fourteenth stage after suffering an accident. Anquetil could be a coolly rational man but he took this prediction seriously. It's thought that he behaved in this self-destructive way at the barbecue because he believed he would probably not finish the stage the following day.

The next day, stage 14, Party Boy didn't even bother to warm up. Poulidor's manager, Antonin Magne, knew that Anquetil would be vulnerable after his day of excess and instructed Poulidor to drop the hammer on the first climb. The other contenders, including Federico Bahamontes, Julio Jimenez and Henry Anglade, also sensed Anquetil's weakness and poor preparation and attacked furiously. The climbing out of Andorra up the Port d'Envalira, a climb new to the Tour that year, started almost immediately. Anquetil was quickly put out the back door. The hard profile of the day's early kilometers gave Anquetil no chance to warm up. At the top, Anquetil was about 4 minutes behind the leaders and was contemplating quitting. He had even loosened his toe-straps.

One of his domestiques , Louis Rostollan, who had stuck with him on the climb shouted at him, "Have you forgotten that your name is Anquetil? You have no right to quit without a fight!" Team director Géminiani came up to Anquetil and bellowed his rage, screaming at him to chase the leaders, to give it all he had in the descent. The story goes that Géminiani gave Anquetil a bottle with champagne in it. With this restorative circulating in the bon vivant's system, he could now effectively compete

Anquetil was by now warmed up. He could use his superb descending skill to catch the leaders through the dense fog on the descent.

Into that fog Anquetil went, riding like a man possessed, taking risks no man should take. He used the headlights and brake lights of the following cars to let him know when to slow for corners. He caught the group with Henry Anglade and Georges Groussard and made common cause with them. From the crest of the Envalira it was 150 kilometers to the finish. Given good fortune he had enough time and distance to salvage his Tour. Using his time trialing skills he made it up to the Poulidor/Bahamontes lead group.

With just a few kilometers to go Poulidor flatted and got a new wheel. His mechanic, in a zeal to make sure he didn't lose any more time, pushed Poulidor before he was ready and caused him to crash. By the time Poulidor was up again and riding Anquetil's group was gone. Poulidor came in with the second group, 2 minutes, 36 seconds behind Anquetil.

Here were the standings after that hair-raising adventure:

The story of Anquetil's Tour being saved with a bidon of champagne is romantic, but Anquetil's wife Jeanine insisted that it wasn't true.

Poulidor hadn't given up yet. Stage 15 was a ride over the Portet d'Aspet, the Ares and the Portillon. Poulidor won it and gained 1 minute, 43 seconds back from Anquetil.

There was still 1 monumental, monstrous day of climbing left. 1 day remained for the pure climbers to try to reclaim the Tour. There were still 2 time trials left to ride, totaling 70 kilometers where Anquetil could easily wipe out his 86 second deficit. He had only to ride defensively and not lose more time, the usual Anquetil formula. Stage 16 was 197 kilometers long and had the Peyresourde, the Aspin, the Tourmalet and the Aubisque climbs. The road turned upward almost immediately with the slopes of the Peyresourde coming at the fourteenth kilometer. Bahamontes took off after only 4 kilometers, quickly followed by his compatriot Julio Jimenez. When they reached the crest of the Peyresourde, Bahamontes let Jimenez take the lead and the climber's points. Bahamontes was looking for bigger fish than the King of the Mountains. He smelled Yellow. Over the Aspin Bahamontes again let Jimenez take the lead over the top. The Anquetil group was 3 minutes back at this point. At the top of the Tourmalet the Anquetil group was over 5 minutes back. But Bahamontes could not descend well and his lead was halved. On the Aubisque Jimenez could no longer stay with Bahamontes. Alone, Bahamontes soared to a lead of over 6 minutes at the top. Back in the field the Pelforth domestiques were rallying and chasing, trying to defend Groussard's Yellow Jersey. On the run-in to Pau Bahamontes's lead was slowly eroded until it was 1 minute, 54 seconds at the end. Bahamontes had been away for 194 kilometers. It was a wonderful ride, but he hadn't gained enough time to hold off Anquetil in the time trials. With 1 of the time trials the very next day, he was surely toast. And Poulidor? He sat in the entire day, recovering from his stage win the day before. Anquetil noted that if Poulidor should win the Tour that year, he should thank Anquetil for the work he did that day holding Bahamontes in check.

The new General Classification:

And then, what must have seemed to be the inevitable happened. Anquetil won the 42.6-kilometer time trial, beating the day's second place Poulidor by 37 seconds. Bahamontes was twelfth, 4 minutes back. Anquetil was now the leader, ahead of Poulidor by 56 seconds. Bahamontes was third at 3 minutes, 31 seconds. Groussard paid the price defending the Yellow for 10 days, and lost 6 minutes. It was now a 2-man race.

Stage 20, with its finish at the top of the Puy de Dôme, was the scene of the 1964 Tour's most dramatic showdown. The Puy de Dôme is an extinct volcano in the center of France. It has an elevation gain of 515 meters in only 6 kilometers. It averages 9%, but gets steeper as the road approaches the summit. The tenth kilometer is almost 13% before it backs off a bit to between 11 and 12%. The final kilometer is still a tough 10%. With such a hard incline, its total 14 kilometers could transform the Tour. Poulidor was the better climber and a tired Anquetil knew it.

Probably 500,000 spectators lined the roads of the old volcano, sure that there would be fireworks that day. Upon reaching the Puy, Julio Jimenez and Federico Bahamontes took off up the mountain. This was as Anquetil wanted. This break took the time bonuses out of play. Poulidor would be riding for just the time gain he might acquire by beating Anquetil if he were so lucky. Poulidor and Anquetil were otherwise unconcerned about the Spanish escape because neither Jimenez nor Bahamontes would be likely to take the Yellow. They were worried about each other. Instead of sitting on Poulidor's wheel, Anquetil rode next to him trying to gain the psychological edge. Neither felt very well. "I never felt again as bad on a bike," Poulidor said later. Anquetil felt worse.

As they closed in on the summit, Poulidor attacked and Anquetil stayed with him. "All I cared was that I was directly next to Raymond. I needed to make him think I was as strong as he, to bluff him into not trying harder."

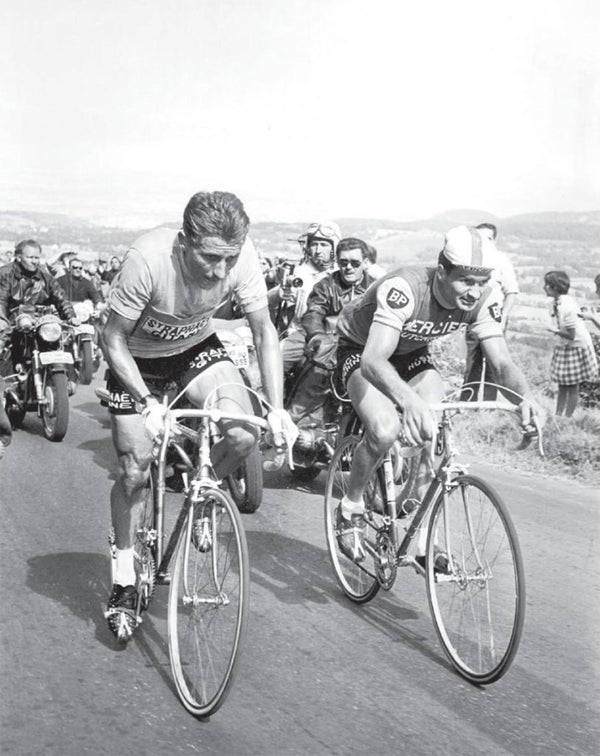

Poulidor attacked again. Anquetil stayed with him. There is a famous picture of Anquetil and Poulidor bumping into each other while climbing the volcano, neither giving in the slightest bit; each trying to cow the other; each riding at his limit.

Passing under the Flamme Rouge (1 kilometer to go flag), Anquetil's attention lapsed for just a moment and he let Poulidor go. There was nothing Anquetil could do. He was spent. Poulidor poured on the gas, racing for the finish line and hoping to erase the 56-second deficit and finally don the Yellow Jersey. He waited at the finish, counting off the seconds.

Anquetil crossed the line, limp with exhaustion, 42 seconds later. He had saved his lead by 14 seconds. Magne, Poulidor's manager, believes that Poulidor could have won the Tour that day if he had used a 42 x 26 as Bahamontes used instead of the 25 that he led Magne to believe was the right choice.

There was the formality of the final time trial in which Anquetil put another 21 seconds between himself and Poulidor. With the time bonus, Anquetil won his astounding fifth Tour de France by 55 seconds over Poulidor.

Poulidor said, "I know now that I can win the Tour."

Final 1964 Tour de France General Classification:

© McGann Publishing

1964 Tour de France: results and classification

General classification of the 1964 tour de france, jerseys of the 1964 tour de france, stages of the 1964 tour de france.

Stage 1 (Rennes - Lisieux, 215 km)

Stage 2 (Lisieux - Amiens, 208 km)

Stage 3a (Amiens - Forest/Vorst, 196.5 km)

Stage 3b (Forest - Forest, 21.3 km in Team Time Trial)

Stage 4 (Forest - Metz, 291.5 km)

Stage 5 (Metz - Fribourg, 161.5 km)

Stage 6 (Fribourg - Besançon, 200 km)

Stage 7 (Champagnole - Thonon les Bains, 195 km)

Stage 8 (Thonon les Bains - Briançon, 248.5 km)

Stage 9 (Briançon - Monaco, 239 km)

Stage 10a (Monaco - Hyères, 187.5 km)

Stage 10b (Hyères - Toulon, 20.8 km in Individual Time Trial)

Stage 11 (Toulon - Montpellier, 250 km)

Stage 12 (Montpellier - Perpignan, 174 km)

Stage 13 (Perpignan - Andorra, 170 km)

Stage 14 (Andorre - Toulouse, 186 km)

Stage 15 (Toulouse - Bagnères-de-Luchon, 203 km)

Stage 16 (Bagnères-de-Luchon - Pau, 197 km)

Stage 17 (Peyrehorade - Bayonne, 42.6 km in Individual Time Trial)

Stage 18 (Bayonne - Bordeaux, 187 km)

Stage 19 (Bordeaux - Brive, 215.5 km)

Stage 20 (Brive - Clermont Ferrand/Puy de Dôme, 237.5 km)

Stage 21 (Clermont Ferrand - Orléans, 311 km)

Stage 22a (Orléans - Versailles, 118.5 km)

Stage 22b (Versailles - Paris, 27.5 km in Individual Time Trial)

- Championship and cup winners

- Club honours

- World Cup: results of all matches

- Winners of the most important cycling races

- Tour de France winners (yellow jersey)

- Best sprinters (green jersey)

- Best climbers (polka dot jersey)

- Best young riders (white jersey)

- Tour de France: Stage winners

- Australian Open: Men's singles

- Australian Open: Women's singles

- Australian Open: Men's doubles

- Australian Open: Women's doubles

- Australian Open: Mixed doubles

- French Open: Men's singles

- French Open: Women's singles

- French Open: Men's doubles

- French Open: Women's doubles

- French Open: Mixed doubles

- US Open: Men's singles

- US Open: Women's singles

- US Open: Men's doubles

- US Open: Women's doubles

- US Open: Mixed doubles

- Wimbledon: Men's singles

- Wimbledon: Women's singles

- Wimbledon: Men's doubles

- Wimbledon: Women's doubles

- Wimbledon: Mixed doubles

- Season Calendar 1964

- Tour de France

Search Rider

Search team, search race, tour de france 1964 | stage overview.

51st edition 22 June 1964 - 14 July 1964

- General Classification

- Tour de France History

- Previous year

The 1964 Tour de France, Part II

Part II of the series looking at the 1964 Tour de France is a stage-by-stage account of the race to show race unfolding from stage wins to accidents, punch-ups to punctures. There are the oddities of the time such as using cabbage leaves to protect against the heat, and the infamous incident of a fortune teller predicting Jacques Anquetil’s death mid-race.

The race starts in Rennes and Edward “Ward” Sels (Solo-Superior) wins Stage 1 and takes the yellow jersey. The Belgian keeps it on Stage 2 , a stage described as “as locked down as a safe” in the pages of L’Equipe and so far no breakaway has managed get a gap on the bunch. André Darrigade, one of the all time sprint greats, wins the sprint.

Stage 3 is a split stage and sees the race cross into Belgium in the morning for what should be a triumphant homecoming for Sels, only his modest team mate Bernard Van de Kerckhove joins a breakaway, wins the stage and takes the race lead, accidentally steal his leader’s thunder. The afternoon has a 21.7km team time trial with a convoluted formula for times but KAS-Kaskol wins and Poulidor’s Mercier-BP-Hutchinson team finishes 14 seconds faster than Anquetil’s Saint Raphaël-Gitane-Campagnolo team while Van de Kerckhove stays in the lead. Sels and Van de Kerckhove aren’t just team mates, they’re room mates that evening and things are frosty.

Stage 4 is a 292km jaunt to Metz where German rider Rudi Altig (Saint Raphaël) wins the stage and gets plenty of applause from the local population, some of whom were born German and became French after the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Thanks to the substantial one minute time bonus Altig propels himself up the GC on the eve of the Tour’s visit to Germany.

Stage 5 and the big news is the race is going to Germany for the first time. Decades before, Tour founder Henri Desgrange loved to take the race to France’s eastern border with Germany and ride into areas that were once German, a sporting version of revanchisme explained in more detail in Nationalism, Psychogeography and the Tour de France . Now the race is actually going into Germany with a finish in Freiburg and Desgrange’s edgy tone is gone, instead gendarmes and Polizei cooperate and L’Equipe describes the stage as a shared endeavour between France and Germany.

It’s 161km, dubbed as short stage for “ le cyclisme moderne ” by the TV commentary, designed make the racing more lively as opposed to the “interminable randonnées which made up the large part of old editions”. The stage crosses the Vosges mountains and the hero of the day is Altig who takes the yellow jersey on home soil, he’d broken away with young French rider Georges Groussard (Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune) with over 100km to go and they’re later joined by three more including Joseph Groussard, brother of Georges, and Willy Derboven (Solo-Superior) who joins as a “policeman” to mark Van de Kerckhove’s yellow jersey and sits on all day which allows him to stay fresh and he wins the stage, a consolation for his team as they lose the yellow jersey.

Stage 6 and a link between 1964 and 1989 as Dutch racer Henk Nijdam (Televizier) takes the stage to Besançon with a late attack. His son Jelle would win two stages of the 1989 edition, also with late attacks.

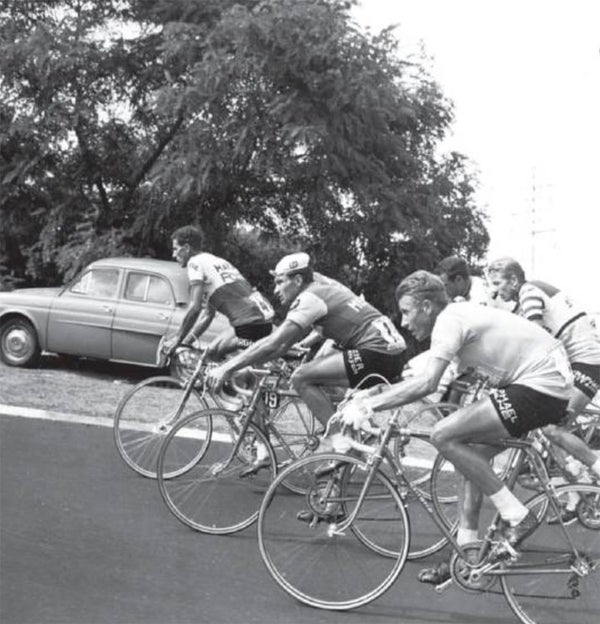

Stage 7 begins after a short bus transfer from Besançon to Champagnole. Today it’s normal and deliberate to have a finish in one town and a start the next day elsewhere but in 1964 this is is a rarity. The transfer is portrayed as modern, and so is the racing, the talk on TV is of the high speed of this edition and how close riders still are on the general classification when in the past they’d have lost or gained minutes so far thanks to splits and mishaps. The 195km route crosses the Jura mountains where Julio Jimenez wins the mountains points on the Col de la Faucille, showing his ambitions for the mountains competition. After the descent a thunderstorm breaks on the race and the conditions get dangerous. The peloton splits with Poulidor and Georges Groussard among the front group of about 20 and they take time on Anquetil with Jan Janssen (Pelforth) the stage winner (pictured above at a later point in the race).

Stage 8 is 248.5km and in the Alps, a giant stage. After an early start at 8.20am they cross three light passes: the Sixt, Marais and Tamié. Then the scale changes in the Maurienne valley and they scale the giant Col du Galibier via the Télégraphe. Anquetil and Poulidor slide into a move mid-stage which is the equivalent of poking a wasps’ nest. Federico Bahamontes (Margnat-Paloma-Dunlop) slips away on the approach to the Télégraphe with Henry Anglade (Pelforth) who is an outsider for the overall classification. Bahamontes floats away from Anglade as soon as they start Télégraphe to lead by 1m30s at the top of the climb but on the short descent Anglade reclaims thirty seconds, a reminder that Bahamontes seemed to climb faster than he could descend. The “Eagle of Toledo” extends his lead on the Galibier with enough time to enjoy the descent to Briançon and the stage win. Behind, Poulidor sets off in pursuit on the Galibier seemingly worried by Bahamontes taking so much time, and finishes second, taking the thirty second time bonus to move up to third overall with Georges Groussard in the same group who takes the yellow jersey. Anquetil had struggled on the Galibier but rejoins on the descent and only to puncture with one 1km go. Who is the favourite to win the race? Poulidor “without a doubt” announces TV commentator Robert Chapatte.

Stage 9 is 239km with the Tour going from Lake Geneva to the Mediterranean in just two days. Bahamontes is first over the 2,802m Col de La Bonette-Restefond with Anquetil and Poulidor close behind and the rest of the race is scattered down the mountain. Things regroup on the descent with a lead group of 22 riders coming into the finish in Monaco on the ash-covered Louis II athletics stadium. Riders jostle for position ahead of the stadium’s entrance knowing it’ll be hard to overtake on the loose surface. Anquetil wins the battle to enter the track but Poulidor overtakes him and sprints for the line… Only the bell rings out and there’s another lap to do, allowing Anquetil to win the sprint for the stage ahead of Tom Simpson (Peugeot-BP-Englebert) and take the minute’s time bonus. Groussard stays in yellow.

Stage 10 is a split stage and the morning’s race is along the Côte d’Azur. Poulidor attacks from the start, presumably his wounded pride is smarting but he is quickly caught. A move containing Nijdam, Altig and Janssen goes clear with 17km to go and Janssen wins the stage to extend his the lead in the points competition.

Stage 10’s second half is a 20km time trial and Anquetil wins, 36 seconds ahead of Poulidor who get 20 seconds and 10 seconds respectively in time bonuses. Groussard finishes 24th and loses 2m51s to Anquetil but stays in yellow.

Stage 11 to Montpellier ends with a sprint finish but it was a lively day in roasting heat. Many riders put cabbage leaves under their caps or better still, put one under the cap and a second is tucked under the back of the cap and hangs out to shade the nape of the neck. Hydration is important and Anquetil reportedly got by with two bidons of tea, six bottles of Coca Cola… and two bottles of beer. The bunch split due to a crash, Anquetil tried a late attack but in the end Ward Sels took his second stage.

Stage 12 sees Nijdam in a late move again but he’s joined by compatriot Jo De Roo (Saint Raphaël) who wins the sprint for the stage win in Perpignan with the Pyrenees on the horizon.

Stage 13 goes to Andorra via the Col de la Perche and the seemingly endless combo of the Col de Puymorens and the Port d’Envalira. Julio Jimenez (KAS) takes off solo at the foot of the Perche and his lead goes up and up and he wins the stage by over eight minutes and closes in on Bahamontes for the mountains competition. Behind Anquetil and Poulidor trade soft attacks but the two big climbs are hard to exploit, the gradual gradients suit sitting on a wheel. Groussard is still in yellow with his Pelforth team mate Anglade now up to third overall.

The race reaches Andorra for the rest day but this is far from benign. A bored Anquetil decides to break with his habit of total rest and goes for a ride and drops by a party held by Radio Andorre for an interview. He’s tempted by some méchoui or a whole roasted lamb where he eats plenty, washed down with plenty of of sangria.

Stage 14 is out of Andorra to Toulouse. Before the Tour had started a fortune teller called Marcel Belline had a column in France Soir , a newspaper, and he had predicted Anquetil would die on Stage 14. Wacky? Yes, only Belline had called various world events and celebrity deaths, for example he foresaw Marilyn Monroe’s suicide in 1962 and President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and plenty more, presumably he had his share of false alarms but newspapers adored his predictions while businessmen and politicians paid beaucoup for private sessions. As soon as the stage started Anquetil was in trouble. Was it nerves about this prophecy or was yesterday’s méchoui misfiring inside or a sangria hangover? Maybe it was all three but what was certain is that he’s dropped on the Envalira as Poulidor and his Mercier team set a fierce pace. It turns out they’d ridden 40km before the stage as a warm-up and their attack was pre-meditated. Yellow jersey Groussard is dropped too but Anquetil is further back and feeling dreadful, ready to quit even. Team mate Louis Rostollan is there to encourage him and push him back on his bike, literally as Anquetil would get a 15 second time penalty for being pushed by up the Envalira. Anquetil’s directeur Raphaël Géminiani hands up a drink, some accounts say it’s whisky, others champagne, but it’s just the tonic and, amid dense fog on the descent, Anquetil picks up Sels, then Groussard and the chase is on. Poulidor is still ahead in a group of seven as they exit the Pyrenees with Anquetil and Groussard’s group about a minute behind and the pursuit lasts 88km during which Poulidor seems to break a spoke in his wheel but he can’t afford to stop for a bike change or a spare wheel. Eventually Anquetil makes it back to Poulidor’s group and things ease up. With 24km to go Poulidor does get a new bike but his mechanic seems too excited and, instead of a helpful push to get going, shoves him to the ground. Anquetil and the others spot this, accelerate and Poulidor is left battling into a headwind and loses 2m36s. The stage is won by Ward Sels. Having hitched a ride to Anquetil Groussard stays in yellow with Poulidor slipping from third to sixth overall.

Stage 15 goes back into the Pyrenees with the Portet d’Aspet, the Col des Ares and the Col du Portillon before a descent to the finish in Luchon. After a calm start there’s a flurry of attacks with Bahamontes and Julio Jimenez duelling for the mountains points. More riders launch moves to win the stage with Tom Simpson and Francisco Gabica (KAS) looking strong. Only for Poulidor to burst out of the peloton on the Portillon, ride straight past Simpson and Gabica, and take the stage by 1m43s on the peloton with Anquetil and Groussard, with Bahamontes a few seconds behind having struggled on the descent. With the attack and the time bonus Poulidor is up 2m43, the misery of the previous day erased.

Stage 16 and more Pyrenees, 197km and the Peyresourde, Aspin, Tourmalet, Soulor and Aubisque. On roads lined with people and reports of the densest crowds ever Jimenez and Bahamontes take off again out of Luchon and battle for the mountains competition. Jimenez is dropped and fights back but Bahamontes is the superior climber and out on the road is the virtual yellow jersey. He clears the Soulor solo and wins the stage. Groussard stays in yellow but Bahamontes is now just 35 seconds behind only the Pyrenees are done and Bahamontes has run out of road. Anquetil is at 1m26s, Poulidor at 1m36s.

Stage 17 is a 42km time trial in the Basque Country with a technical, hilly course. Anquetil wins the stage while George Groussard implodes, losing 5m59s and the yellow jersey. Anquetil is the new race leader but Poulidor “only” loses 37s on the stage to keep him in contact on the general classification, he’s less than a minute down with Bahamontes at 3m31s.

Stage 18 is almost a home start for André Darrigade, the top sprinter in his day. Only his day was a few years ago, he is 40 now. In a hectic finish he surges past Barry Hoban (Mercier) who looked to have the stage and wins in Bordeaux. It’s Darrigade’s 22nd career Tour de France stage win and his last.

Stage 19 is marked by tragedy. A vehicle in the publicity caravan skids on a tight bend in Port-de-Couze, a town on the banks of the Dordogne river. Seeing the danger the waiting crowd are moved to the other side of the road, only for a police tanker truck to lose control on the same bend but this time it swerves to the other side of the road, hitting the crowd and falling into a canal, taking many people into the water with it. Nine people die and many sustain grave injuries. People in the crowd spontaneously start a rescue mission, one spectator plunges into the canal to rescue the driver and more lives are saved. The race reaches the drama within a few minutes and the Tour’s medical staff work to help the victims as stunned riders look on, grizzly reports write of body parts in the canal. It’s the Tour de France’s worst tragedy and there is a memorial plaque beside the road today.

The riders resume the route but in a slow procession at first and a few kilometres later someone beside the road, presumably unaware of the tragedy, insults the riders for being lazy. Pierre Everaert gets off his bike to punch the man and the police are required to pull him off. The racing gets frantic for the final 20km and it’s a sprint and there’s a big crash within sight of the line which takes out plenty and Ward Sels wins again ahead of Mario Minieri (Salvarini) who broke his cleats just as he launched his sprint.

Stage 20 is the defining stage of the race, the battle between Anquetil and Poulidor on the Puy-de-Dôme that gives rise to the iconic photo which stands out as a highlight of the decade, possibly of a century of the sport. Only material from the time is rightly marked by the previous day’s tragedy. Poulidor is just 56 seconds down on Anquetil and better suited to the punchy summit finish with the final 4.5km at 11% and there’s a minute’s time bonus waiting at the top. Poulidor’s Mercier team get to work with a high tempo and as they start the final climb the lead group is down to 11 riders and as they reach the double-digit gradients with 5km to go it’s down to four riders: Bahamontes and Jimenez as the best climbers in the race and still locked in a contest for the mountains jersey, plus Anquetil and Poulidor as first and second overall. At 4km to go Jimenez attacks and moments later Bahamontes takes off in pursuit. It’s advantage Anquetil now as the time bonus Poulidor needs starts to look out of reach. The two match each other, riding side by side at times. With 900 metres to go Poulidor attacks and Anquetil’s bluff can last no longer and he cracks, conceding 42 seconds to Poulidor. It leaves Anquetil in yellow but only by 14 seconds, “13 seconds too much” he quips out of exhaustion at the summit but he’s tiring with the Giro in his legs.

Stage 21 and a 311km trip north to Orléans, transfers may be a new thing in 1964 but they’re still rare and the riders have to reach Paris under their own steam. The start sees Bahamontes send a team mate up the road early right at the start to take the mountains points at the Côte du Cratère and it’s job done for Joseph Novalès who wins the points making it arithmetically impossible for Jimenez to win the mountains competition, thus Bahamontes will win his sixth mountains competition. A break forms with 40km to go and the peloton sits up, letting the six quickly take time and it’s from the move that Jean Stablinski (Saint Raphaël), in his French champion’s jersey, wins the stage.

Stage 22 is a 118km morning spin from Orléans to Versailles. Still just 14 seconds down Raymond Poulidor tries an attack but it’s too obvious. Instead it’s the world champion Benoni Beheyt (Wiel’s-Groene Leeuw) who wins the stage, a prestigious win for a rider whose rainbow bands are not as illustrious as he’d like after being accused of “betrayal” in the Worlds where compatriot Rik Van Looy is the big favourite only for Beheyt to pip him in the sprint, a touch of lèse-majesté but Beheyt’s supporters say Van Looy was too confident, launching his sprint from afar and was fading so Beheyt’s move ensured a home win. Van Looy has abandoned this Tour in the first week but is a giant in the sport at the time with a prolific palmarès featuring every one day race worth winning.

The second part of Stage 22 is the final time trial from Versailles to Paris, 22km and on big boulevards lined by dense crowds. Anquetil is still just 14 seconds ahead of Poulidor with a 20 second time bonus up for grabs. It’s advantage Anquetil as the time trial specialist of his era but he’s deep into the third week of the second grand tour of the year, and besides a puncture is sufficient to spoil things. The duel is close with only a few seconds in it with Poulidor catching and passing Bahamontes and able to profit from the draft. It’s close between the pair until the final minutes when Poulidor starts to fade. Anquetil wins the stage with Rudy Altig second at 15s and Poulidor third at 21s.

The final classification sees Anquetil win his fifth Tour de France and his fourth consecutive victory with Poulidor second overall at 55s, the closest ever winning margin in the race so far (and still the ninth closest Tour today). Bahamontes is third at 4m44s and wins the mountains prize. Jan Janssen wins the points competition. Pelforth-Sauvage-Lejeune win the team competition thanks to Anglade, Groussard and André Foucher finishing fourth, fifth and sixth overall respectively. 132 riders started, 81 finished and the average speed was 35.4km/h.

Stage wins by team :

- St Raphaël: Anquetil x 4, Altig, De Roo, Stablinski = 7

- Solo-Superior: Sels x 4, Derboven, Vandekerckhove = 6

- Margnat-Paloma: Bahamontes x 2, Darrigade x 2 = 4

- KAS: Jimenez x 2, team time trial = 3

- Pelforth: Janssen x 2 = 2

- Mercier: Poulidor

- Televizier: Nijdam

- Wiel’s-Groene Leeuw: Beheyt

Conclusion That’s the stage-by-stage processional account and if this is a long post, well it was a three week race. Indeed the events each stage are edited and abbreviated. The racing was often lively with moves surging clear, being caught, new attacks going and so on and this piece is long enough already without detailing all of each stage’s action from KM0 to the finish and listing the crashes and abandons. Even the flat stages could see a lot of action, only of course there was little TV coverage.

The point of this blog post is to put a bit more structure to the race and to view it day-by-day, to see how the Tour slowly unfolded rather than just look back at what made it such a good race. These days we equate the 1964 Tour to the Anquetil-Poulidor duel but there was a lot more going on, whether Jimenez and Bahamontes in the mountains, Groussard’s strong ride, Sel’s stage wins and more. The next and final part of this mini-series will try to look back at what made this such a good race and why it stuck in the memory.

1964 Tour de France – Part I to set the scene 1964 Tour de France – Part II a stage-by-stage account of the race 1964 Tour de France – Part III a review of what made it so good

- Sources: L’Equipe/Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ina.fr video archives, Tours de France by Antoine Blondin, memoire-du-cyclisme.eu , lagrandeboucle.com

48 thoughts on “The 1964 Tour de France, Part II”

A great read. Thank you.

Having no idea what you do, Mssr Inrng, for a living–perhaps you are an author?–have you thought of writing a book?

An amateur blogger here (which helps explain the typos etc). I’ve so much material on the 1989 Tour, plenty thanks to readers who were generous with their time, the idea of a book was of interest but in a way it’s too limiting to stick to text. There’s too much colour, music, photo, sound, video and more to encapsulate that maybe a film or documentary would be a better avenue but that’s way beyond a niche blog. I’ll still return to 1989 in time on here though.

as a doc filmmaker i can only agree that a doc is a bit more than a niche blog in terms of scale of undertaking… the niche blog is a great form in any case!

Fascinating stuff, the stage by stage run down bought it to life. 1989 Tour remains my favourite but probably only because it was my third one and with so much changing of fortunes compared to what came later. Thank you.

Thanks for this – fantastic, what a race it must have been.

Incredible photo really. Is there a better one in the sport?

It is a great photo. The best? That’s a matter of taste. There’s an interesting story to it too, more on that in the next piece.

Would love to hear how they came to be so close to each other (a similar contact in a modern sprint finish could see a DQ!) Is there any film footage of the incident?

Hyperbole surely? Nudges up a climb are regularly in evidence, and the riders would really need to nut one another for a DQ. The picture looks more like two riders on a tight road being so caught up with riding they inadvertently collide briefly.

Here’s the film from the day: https://www.ina.fr/video/I00007448/duel-poulidor-anquetil-au-puy-de-dome-video.html

You can see them Poulidor riding side by side in a duel, a half-wheeling competition. At one moment for the photo they bump shoulders but as the video shows they were side by side for longer parts of the climb.

Lovely as usual. The Guardian has been running similar, though in real time accounts of other sports. I’m sure they might be interested in your wonderful analysis. Do you need an in?

Thanks but happy with this blog, it’s enough.

We all are grateful for your time, talent, expertise and passion for painting these wonderful pictures for us.

Hear, hear. The quality of this blog is incredible and I’m very thankful to Inrng for all of the hard work and expertise put into every post.

Thanks. I ended up getting interested in the 1989 Tour and going into the last week people knew they were enjoying an exceptional edition and 1964 Tour kept coming up as a reference point so this has been a good way to go and explore the topic, having to type up a few pieces helps condense the notes, thoughts down so happy to share a view of it all.

For a long time the history side of the sport has been something that’s important to the sport but I never got too into it but the more you explore it, the more interesting it gets especially as you can cherry-pick the best races.

Ah, poor Pou Pou. That broken spoke cost him dearly. What might have been? If he’d have broken Anquetil’s streak would he have won more? Sport goes like that – victory hangs on a moment of fate, and somehow the luck sits with the favourite. It’s interesting to read about the manner of victory and the responses to certain events, such as Sels and as Van der Kerkove. Did VdK’s win really make for frosty relations? I presume he was in the break to come the move on the teams behalf. Also interesting to read about the terrible accident on stage 19. I wonder whether the Tour would be cancelled now, or a go slow out in place for the following day’s race? But on the basis that the incident was not caused by the cyclists racing they might continue the Tour as a way of respecting the spectators themselves? Certainly some of the roads the caravans go down are ill suited to vehicles of their size. Thanks so much for the write up. I’ve read appreciated histories of these events but this is a really great stage-by-stage breakdown and really brings home the excitement of the ‘64 edition.

Great stuff, merci beaucoup as they say! I’ll throw in an unabashed plug for my friend Bill McGann’s TdF book here https://bikeraceinfo.com/tdf/tdfbook1.html Looking forward to your next installment as well as your 1989 Tour posts. Part of my “luckiest man on earth” claim is that I was able to follow a lot of La Grande Boucle 1989 in-person and attend some exclusive interviews with the eventual winner before and during that unforgettable event.

What a wonderful read! Thank you so much for this thorough and engrossing account. I look forward to your analysis piece with great anticipation!

Cycling was such a different world and that 1964 world is so well captured in the article. Many of the stages were covered at 34km/h or less with the 1964 race average 35,419 km/h, a speed some keen cyclotourists could maintain – though maybe not for 21 stages. What explains the relatively modest pace: – equipment though only partly and then mostly in the mountains – roads, maybe a little – clothing, quite substantially – stages distances, yes, but as much due to an understanding to take it easy for much of the stage as sheer physical capacity – training techniques, certainly – absence of continuous TV as motivation – large teams and low team numbers

I like to wonder about these things myself, the difference between then and now. So much has changed.

I think that top riders like Merckx, Anquetil in their prime were still very close to what they could be with today’s training. We are lucky we have the world hour record to look at here. I always love to think about the fact that Boardman only put 10 metres into Merckx even when he had advantages in clothing and wheels for far more. And the fact that Merckx’ pacing is widely recognized to be really bad.

Perhaps today the domestiques are a lot better compared to then, and perhaps the riders can hit their peak more predictably and more often – but the top riders back then, when they were in top form would still be world class today.

Training techniques have not really improved. It pisses me off no end that people consider this to be a factor. Back in the day they were pretty close to preparing at their peak. Perhaps there’s a bit more knowledge about over training, and the pros back then were more prone to this. The tendency is to underestimate our predecessors because we believe in the infinite progression of science. To some degree this is true, but only if you take in the dark arts it creates. Around the late sixties blood doping appears on the scene, at the same time as heart rate monitors. Before that there’s amphetamines, cocaine, cortico and anabolic steroids. Thereafter you have the development of EPO and HGH, but which have massively increased speeds – not that speeds have ever significantly decreased despite the claims about testing. One of the biggest differences has been the equipment, but even before Anquetil we know that doping was part of the cycling scene (“in short we ride on dynamite”). What gets me is this trope that ‘modern training’ and ‘diets’ have improved things. The science behind all of it has not changed in a long time. It used to be the case that British athletes would go to Australia to do their winter training. The truth of the matter was that they could escape the U.K. testers, and Australians were not so shy about playing by the rules (they never have been – in the current world that’s only criticism if you believe that sport is a level playing field). But they would all say it was about ‘better training/weather/diet’ when training in sunshine makes no difference, and you could get all the same food here. In the field of cycling the trend to train in one place or the other depends on the local laws about doping and where the “best” doctors are based. I’ll take stage distances as a limiting factor though (and carbon frames). That’s just natural physiology. You can’t race over longer distances. I’m pretty sure that Anquetil’s bidon was laced with amphetamines – I forget which tour it is where he appears pretty loopy.

Training techniques have improved massively. It pisses me off no end that people consider the only progression in sports science to be ‘better doping’.

OK. So what has improved massively?

I’d suggest riders today can get fitter quicker. It seemed more haphazard in the past with riders doing steady distances over the winter and then using early season races as training events and then other races throughout the year to keep fit. Effort and fatigue can be better measured today although still sometimes indirectly.

Poulidor’s DS Antonin Magne was seen as an expert on sports science in his day, writing books on training and nutrition but accounts of them make it all sound basic (which isn’t a bad thing, simplicity helps).

Over training/racing and long distance stages are likely to reduce the speed, and collectively the understanding of timing your form for a race has probably improved to some degree, but few cyclists are allowed this luxury. Lazy assumptions about training techniques have repeatedly allowed athletes to achieve surprising results. Anyone remember ‘Mo Farah’? I don’t think we should really let athletes off the hook. I understand people won’t agree with me. But I won’t let people shut their minds off to these things. Every time I see Ronaldo with his shirt off, and reports about his legendary ability in the gym I think “oh, corticos, eh?”

One thing you left out that I think may explain a lot of the difference between then and now is that the racers back-in-the-day raced so much more. Far, far less of the concentration solely on LeTour each season that is so prevalent today would seem to explain it along with the other things you mentioned. It’s a funny thing though, I can remember some a-hole (ol’ Heinie perhaps?) going on about how nobody would watch a grand tour run off at speeds slower than they were going during the BigTex era. I wondered why? Who cares about average speeds? IMHO fans want to see competition, head-to-head racing, tactics, spectacle, drama, desire and skill demonstrated on the road, whether the average speed is 30 or 40 kph.

Good point again Larry. Many top riders would ride two GTs, most one day classics, a few one week stage races (Midi-Libre, PN…), numerous minor races and some semi-serious crits. A lot of riding and a lot of intensity with no in-season “fallow” period as now. PCS gives 7007kms for Poulidor in 1964 which must be far from complete. They must have been empty well before the end of the season though at least they didn’t have to go to China to end the season or Australia to start it. How often did Poulidor fly to events (Milan-San Remo and Lombardy by car probably). The whole environment was almost too different to compare.

On your last average speed point, TV covered only the final part of each stage while the French in thier villages would have been happy to see the riders pass by the local bar whether at 28km/h or 40.

I’d add food and drink to the list here, there are regular tales of riders cracking spectacularly, presumably they run out of energy or are massively dehydrated, or both. Plus the evening meals and breakfasts were different.

I’d definitely agree on the food and drink angle. I was relatively seriously into athletics in the late 1970s and there was next to no understanding of diet and eating on competition day. The only rule I recall was to eat nothing for at least 3 hours before your race. Glucose tablets were about but there was no thought of continual hydration and feeding to boost or maintain energy levels.

It’s hard trying to imagine the rider’s life on tour in 1964. No air-conditioned coaches with showers and coffee machines, the drive back to the hotel crammed into a Simca Aronde with a pile of spare wheels, while those of my age will recall the pre-chain rural hotels in France: ten tiny double bedrooms for one small bathroom along a creaky corridor, hot water for the first served…and no team chefs to prepare tasty and balanced meals.

It wasn’t a lot better than that even in the late 1980’s. I can remember sweating like a pig driving all over France in a non-air conditioned Fiat Ducato (or worse, a Renault Trafic) crammed full of vacation clients and their luggage with 10 bikes on the roof. Some of the hotels were as you described (we shared a few with various teams along the way) while the Campaniles and such weren’t much better except for their individual bathrooms vs the down-the-hall awfulness. Food was pretty bad as well – the Italian teams often had a small camper in the parking lot with a guy boiling (properly) up some dry pasta and serving it with jarred sauce. It was grueling and we were just RIDING around rather than racing. We were only half joking when we told our clients “This ain’t no vacation – it’s an adventure!”

The Campanile chain started in 1976 (Ibis 1974) so Poulidor and his team didn’t have the pleasure. They were – at least at first – clean, practical and predictable, and soon accounted for hundreds of Modernes, Cheval Rouges et Blancs, Voyageurs, Terminus, and Commerces all over France. Poor compensation after 250kms on a Stronglight, Simplex and Mafac fitted steel frame. At least they never had the DS screaming “Move up” on the radio, or a spare tubular wrapped around thier shoulders.

And my first high summer 3000kms in France was in an overheating Anglia with slipping clutch. Great days.

IBIS was the other one but I couldn’t recall (blocked out?) the name. Slap-dash construction using what seemed to be the cheapest materials possible, which deteriorated quickly, as did the cleanliness. And way-too-many of ’em, despite being in France, lacked a bidet! Even if you didn’t know what it was for, you could use it to do your laundry. Later there were the equally-awful FastHotel and such, exceeded in awfulness only (later?) by Formula 1. We visited a few teams who were stuck in FastHotels, often backed up to the autoroute so our interviews were conducted trying to hear over the din of traffic. Ah, those were the days – but OTOH I wouldn’t mind a “Stronglight, Simplex and Mafac fitted steel frame.” especially if it was from an Italian “builder of trust”.

A steel frame from a “builder of trust”. I much regret giving away custom made Ellis-Briggs, Mercian and Woodrup frames during a temporary loss of cycling interest in the nineties. As for the trust, I once got a new frame home only to find the BB cup would not enter as the BB shell had visibly deformed (during brazing?). The reputed builder had not even bothered to run a tap through to clean the threads or he would have seen the problem.

Stronglight, yes, Mafac, maybe, but try changing down on Simplex at a delicate moment on the lower slopes.

Sorry to drift off topic Mr IR

Through my rose-colored glasses I thought of SIMPLEX and imagined those wonderful retro-friction shifters (rather than cheezy plastic derailleurs) attached to a lugged/brazed steel masterpiece from one of the (mostly) Italian builders-of-trust of the day. 🙂

Niche fact: Ward Sels’s victory in the first stage was the last time a debutant won their very first stage of Le Tour until Fernando Gaviria in 2018.

This was a fascinating read. Thank you for this type of content! I was not aware of the Stage 19 tragedy. A little investigation showed the intersection where this happened (at D660 and D703 based on Streetview analysis) is completely different 56 years later. There appears to be monument outside the small hotel there now. If something like this were to happen today can anyone imagine the stage would continue?? Thanks for the context around that famous photo on Puy de Dome!

They continued (some racing for the stage win) despite the death of Fabio Casartelli in 1995. I was there near the finish as reports began to come in, so I’d guess most (if not all?) of the riders knew soon enough as well. What would you expect them to do? The day-after is the day to show your respect but contrast this one with 1995’s. A go-slow would have robbed us of the famous duel, perhaps what “Mr. 60%” was thinking when he expressed displeasure with the go-slow?

For Casartelli a lot of the riders and people in the race didn’t know what happened. With the Port-de-Couze deaths, the race certainly knew what happened as the reports on the scene were very graphic with riders looking down from the bridge into the water below. However it seems they had little other option to ride on and eventually set off at a slow pace, which accounts for the punch-up incident later on. There is a large memorial beside the road to the incident.

There are more recent examples too, Goolaerts on Paris-Roubaix or Lambrecht in Poland. I assume most people didn’t know the extent of the incident until after the race was over, and if there has to be a response in the race (neutralization of a stage for instance), it would have to wait until the next day.

I wonder, actually, would Radio Tour would relay the gravity of the injuries of a rider during a race? and if so, would a DS inform his riders before the stage is over?

Later reports said many riders were informed by their teams during the stage though Radio Tour was criticized for not making a general announcement. I guess one could argue how far the news spread in the peloton during the stage but my memory is that few continued racing at full-cry and plenty of race fans (who had all pretty much heard about it by then) wondered if the ones who did didn’t know or didn’t care? Note the Giro stage didn’t stop for Weyland’s death either as IMHO there’s just too much confusion and rumor when these things happen to expect the entire peloton to just stop and climb off their bikes. Pay your respects the next day, then get on with it.

Thanks for this! I’ve been eking it out over the last couple of days. Just what the doctor ordered.

All things considered, the Tours of 1964 and 1989 are basically two-character dramas, with some extra subplots. In that sense, I think I still prefer 1983, with a wider cast of main characters, more narrative twists, and more complex tapestry of plots. To this day, my favourite TdF of them all.

Ferdi – have you got a link or anything to more fully illustrate your reasons for this opinion? All I can think of is “23 Days in July” which didn’t come close to what you describe, nor did this http://www.bikeraceinfo.com/tdf/tdf1983.html so I’d enjoy reading or viewing anything you can point me to. Grazie!

http://www.lagrandeboucle.com and memoireducyclisme do a great job of summarizing and giving the standings (but they’re in French). As for the narrative, the Luchon I think it’s worth looking at that Tour from the point of view of all the possible contenders. The Peugeot story is only one them (but the one that interests English speakers, because of Anderson, Millar and Roche). There is a strong Colombian narrative (Colombians were decisive), but also the Van Impe story (he was perhaps the strongest man in the race, but he missed the train on the way to Luchon, lack of daring), the other 1970’s stars swan songs (Zoetemelk, Agostinho) the Ti-Raleigh story (Winnen, Lubberding, how they tried to turn the race around on the way to Morzine), the Reynolds story (their number on the Puy de Dôme TT, Spain’s comeback to the Tour as a major force), and of course the Renault-Fignon story. That one day when Kelly wore yellow and was a candidate for the overall. Bernaudeau was a challenger too, and had his moment. 1983 was fascinating, the throne was vacant, the course was really brutal, no one was in control of the race, at any point.

Thanks. Sadly there’s no way I can share your opinion on this race as at the time I was 100% devoted to two-wheeled exploits of another kind, so I’ve got nothing in the way of first-hand memory other than the accounts I listed. CBS TV in the USA got interested later, just as that other two-wheeled interest waned, so the time was right for me in many ways. Perhaps Mr. Inrng might tackle the 1983 TdF for us as it does sound like a lot was going on as various dramas played out besides what was described in 23 Days in July?

Wonderful stuff, thanks a lot.

Stage 14 deserves a blog post of it’s own! What a story.

surely that was when the race was won?… well not lost anyway…

Comments are closed.

Powered by Outside

ANQUETIL vs. POULIDOR: The ultimate showdown at the Tour of ’64

Words by john wilcockson with images from horton collection.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Reddit

Don't miss a moment of the 2024 Tour de France! Get recaps, insights, and exclusive takes with Velo's daily newsletter. >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Sign up today! .

RAYMOND POULIDOR died on Wednesday morning in his hometown of St. Léonard-de-Noblat. He was 83. He was perhaps the most popular French rider in history. This is the story of his finest Tour de France, a race he would never win, that established his reputation as the greatest racer never to wear the maillot jaune .