Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who explored Central America, overthrew Montezuma and his vast Aztec empire and won Mexico for the crown of Spain.

(1485-1547)

Who Was Hernán Cortés?

Born around 1485, Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador and explorer who defeated the Aztecs and claimed Mexico for Spain.

He first set sail to the New World at the age of 19. Cortés later joined an expedition to Cuba. In 1518, he set off to explore Mexico.

Cortés strategically aligned some Indigenous peoples against others and eventually overthrew the vast and powerful Aztec empire. As a reward, King Charles I appointed him governor of New Spain in 1522.

Cortés, marqués del Valle de Oaxaca, was born around 1485 in Medellín, Spain. He came from a lesser noble family in Spain. Some reports indicate that he studied at the University of Salamanca for a time.

In 1504, Cortés left Spain to seek his fortune in New World. He traveled to the island of Santo Domingo, or Hispaniola. Settling in the new town of Azúa, Cortés served as a notary for several years.

He joined an expedition of Cuba led by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar in 1511. There, Cortés worked in the civil government and served as the mayor of Santiago for a time.

Aztec Empire

In 1518, Cortés was to command his own expedition to Mexico, but Velázquez canceled it. In a mutinous act of defiance, Cortés ignored the order, setting sail for Mexico with more than 500 men and 11 ships that year.

In February 1519, the expedition reached the Mexican coast. By some accounts, Cortés then had all his ships destroyed except one, which he sent back to Spain. This brazen decision eliminated the possibility of any retreat.

Cortés became allies with some of the Indigenous peoples he encountered, but with others, he used deadly force to conquer Mexico. He fought Tlaxacan and Cholula warriors and then set his sights on taking over the Aztec empire.

He marched to Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital and home to ruler Montezuma II . After being invited into the royal palace, Cortés took Montezuma hostage and his soldiers plundered the city.

But shortly thereafter, Cortés hurriedly left the city after learning that Spanish troops were coming to arrest him for disobeying orders from Velázquez.

After fending off the Spanish forces, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán to find a rebellion in progress, during which Montezuma was killed. The Aztecs eventually drove the Spanish from the city, but Cortés returned again to defeat them and take the city in 1521, effectively ending the Aztec empire.

In their bloody battles for domination over the Aztecs, Cortés and his men are estimated to have killed as many as 100,000 Indigenous peoples. King Charles I of Spain (also known as Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) appointed him the governor of New Spain in 1522.

Later Years and Death

Despite his decisive victory over the Aztecs, Cortés faced numerous challenges to his authority and position, both from Spain and his rivals in the New World. He traveled to Honduras in 1524 to stop a rebellion against him in the area.

In 1536, Cortés led an expedition to the northwestern part of Mexico, in the process exploring Baja California and Mexico's Pacific coast. This was to be his last major expedition.

Back in the capital city, Cortés found himself unceremoniously removed from power. He traveled to Spain to plead his case to the king, but he was not reappointed to his governorship.

In 1541, Cortés retired to Spain. He spent much of his later years desperately seeking recognition for his achievements and support from the Spanish royal court. Wealthy but embittered from his lack of support and acclaim, Cortés died in Spain in 1547.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hernán Cortés

- Birth Year: 1485

- Birth City: Medellín

- Birth Country: Spain

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who explored Central America, overthrew Montezuma and his vast Aztec empire and won Mexico for the crown of Spain.

- Politics and Government

- War and Militaries

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1547

- Death date: December 2, 1547

- Death City: Castilleja de la Cuesta

- Death Country: Spain

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- I love to travel, but hate to arrive.

- He travels safest in the dark night who travels lightest.

- Better to die with honor than live dishonored.

European Explorers

Was Christopher Columbus a Hero or Villain?

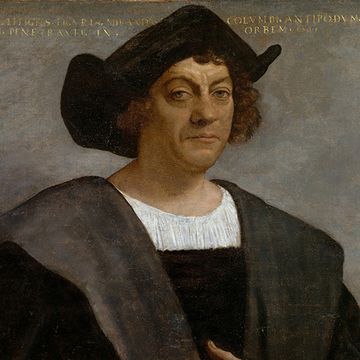

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

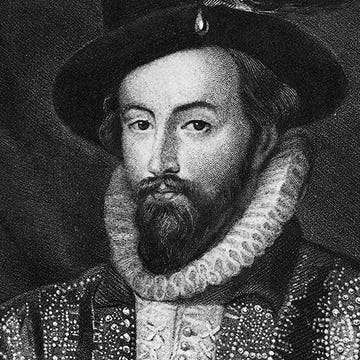

Sir Walter Raleigh

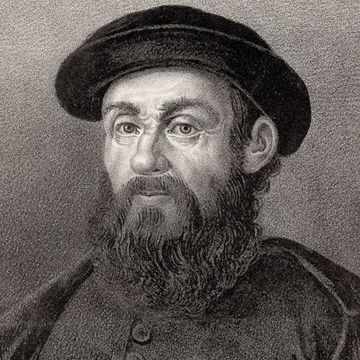

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Hernán Cortés: Master of the Conquest

On Aug. 13, 1521, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés received the surrender of Cuauhtémoc, ruler of the Aztec people. The astonishing handover occurred amid the ruins of Tenochtitlan, the shattered capital of a mighty empire whose influence had stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific and extended from central Mexico south into parts of what would become Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. After an 80-day siege Cortés had come to a terrible resolution: He ordered the city razed. House by house, street by street, building by building, his men pulled down Tenochtitlan’s walls and smashed them into rubble. Envoys from every tribe in the former empire later came to gaze on the wrecked remains of the city that had held them in subjection and fear for so long.

But how had Cortés accomplished his conquest? Less than three years had passed since he set foot on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, yet he had destroyed the greatest power in Mesoamerica with a relative handful of men. His initial force comprised 11 ships, 110 sailors, 553 soldiers—including 32 crossbowmen and 13 bearing harquebuses (early firearms)—10 heavy guns, four falconets and 16 horses. The force size ebbed and flowed, but he never commanded more than the 1,300 Spaniards he had with him at the start of the final assault.

On its face such a victory would suggest Cortés was a commander of tremendous ability. Yet scholars of the period have long underrated his generalship, instead attributing his success to three distinct factors. First was the relative superiority of Spanish military technology. Second is the notion smallpox had so severely reduced the Aztecs that they were unable mount an effective resistance. And third is the belief Cortés’ Mesoamerican allies were largely to credit for his triumph.

That the Spaniards enjoyed distinct technological, tactical and cultural advantages over their Mesoamerican foes doesn’t mean Cortés’ victories came easy

The conquistadors’ military technology was unquestionably superior to that of every tribe they encountered. The warriors’ weapons and armor were made of wood, stone and hide, while those of the Spaniards were wrought of iron and steel. Atlatls, slings and simple bows—their missiles tipped with obsidian, flint or fish bone—could not match the power or range of the crossbow. Clubs and macuahuitls—fearsome wooden swords embedded with flakes of obsidian—were far outclassed by long pikes and swords of Toledo steel, which easily pierced warriors’ crude armor of cotton, fabric and feathers. And, finally, the Spaniards’ gunpowder weapons—small cannon and early shoulder-fired weapons like the harquebus—wreaked havoc among the Mesoamericans, who possessed no similar technology.

The Spaniards also benefitted from their use of the horse, which was unknown to Mesoamericans. Though the conquistadors had few mounts at their disposal, tribal foot soldiers simply could not match the speed, mobility or shock effect of the Spanish cavalry, nor were their weapons suited to repelling horsemen.

When pitted against European military science and practice, the Mesoamerican way of war also suffered from undeniable weaknesses. While the tribes put great emphasis on order in battle—they organized their forces into companies, each under its own chieftain and banner, and understood the value of orderly advances and withdrawals—their tactics were relatively unsophisticated. They employed such maneuvers as feigned retreats, ambushes and ambuscades but failed to grasp the importance of concentrating forces against a single point of the enemy line or of supporting and relieving forward assault units. Such deficiencies allowed the conquistadors to triumph even when outnumbered by as much as 100-to-1.

Deeply ingrained aspects of their culture also hampered the Aztecs. Social status was partly dependent on skill in battle, which was measured not by the number of enemies killed, but by the number captured for sacrifice to the gods. Thus warriors did not fight with the intention of killing their enemies outright, but of wounding or stunning them so they could be bound and passed back through the ranks. More than one Spaniard, downed and struggling, owed his life to this practice, which enabled his fellows to rescue him. Further, the Mesoamerican forces were unprepared for lengthy campaigns, as their dependence on levies of agricultural workers placed limits on their ability to mobilize and sustain sufficient forces. They could not wage war effectively during the planting and harvest seasons, nor did they undertake campaigns in the May–September rainy season. Night actions were also unusual. The conquistadors, on the other hand, were trained to kill their enemies on the field of battle and were ready to fight year-round, day or night, in whatever conditions until they achieved victory.

That the Spaniards enjoyed distinct technological, tactical and cultural advantages over their Mesoamerican foes does not mean Cortés’ victories came easy. He engaged hundreds of thousands of determined enemies on their home ground with only fitful opportunities for reinforcement and resupply. Two telltale facts indicate that his success against New World opponents was as much the result of solid leadership as of technological superiority. First, despite his sparse resources, Cortés was as successful against Europeans who possessed the same technology as he was against Mesoamerican forces. Second, Cortés showed he could prevail against the Aztecs even when fighting at a distinct disadvantage.

In April 1520, as the position of the conquistadors in Tenochtitlan became increasingly precarious, then Aztec ruler Montezuma II—whom the Spaniards had held hostage since the previous November—was informed Cortés’ ships had arrived at Cempoala on the Gulf Coast bearing the Spaniard’s countrymen, and he encouraged the conquistador to depart without delay. While Cortés’ troops were elated at what they assumed was impending deliverance, the commander himself rightly suspected the new arrivals were not allies. They had been sent by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, governor of Cuba, whose orders Cortés had disobeyed in 1519 to launch his expedition, and their purpose was to punish rather than reinforce.

Reports from the coast indicated the fleet comprised 18 ships bearing some 900 soldiers—including 80 cavalrymen, 80 harquebusiers and 150 crossbowmen—all well provisioned and supported by heavy guns. The captain-general of the armada was Pánfilo de Narváez, a confidant of Velázquez, who made no secret of his intention to seize Cortés and imprison him for his rebellion against the governor’s authority.

Cortés could not afford to hesitate and thus allow Narváez time to gather strength and allies. Yet to march out of Tenochtitlan to engage the new arrivals also presented significant risks. If Cortés took his entire force, he would have to abandon the Aztec capital. Montezuma II would reassume the throne, and resistance would no doubt congeal and stiffen, making re-entry a matter of blood and battle, in contrast to the tentative welcome he had initially received. But to leave behind a garrison would further reduce the size of the already outnumbered force he would lead against Narváez. With the swift decision of the bold, a factor indeterminable by numerical calculation, the Spanish commander chose the latter course.

Cortés marched out with only 70 lightly armed soldiers, leaving his second-in-command, Pedro de Alvarado, to hold Tenochtitlan with two-thirds of the Spanish force, including all of the artillery, the bulk of the cavalry and most of the harquebusiers. Having done all he could to gain an edge over Narváez by feeding his couriers misinformation and undermining the loyalty of his officers with forwarded bribes of gold, Cortés marched with all speed. He crossed the mountains to Cholula, where he mustered 120 reinforcements, then marched through Tlaxcala and down to the coast at Veracruz, picking up another 60 men . Though still outnumbered more than 3-to-1, Cortés brought all his craft, daring and energy to bear and, in a rapid assault amid heavy rain on the night of May 27, overwhelmed his foes. Narváez himself was captured, while most of his men, enticed by stories of Aztec riches, readily threw in their lot with Cortés. Soon after his surprise defeat of Narváez, the bold conquistador proved himself equally capable of defeating Mesoamerican forces that held a numerical advantage.

The bold conquistador proved himself equally capable of defeating Mesoamerican forces that held a numerical advantage

On his return to Tenochtitlan, Cortés discovered Alvarado had indulged in an unprovoked massacre of the Aztecs, stirring the previously docile populace to murderous fury. The Spaniards quickly found themselves trapped and besieged in the capital, and hard fighting in the streets failed to subdue the enemy. Not even Montezuma could soothe his people, who met their emperor’s appeal for peace with a shower of stones that mortally wounded him. With the Spanish force growing short of food and water, and losing more men by the day, Cortés decided to withdraw from the city on the night of June 30–July 1. After a brutal running fight along a causeway leading to shore, the column was reduced to a tattered remnant, leaving Cortés with no more than one-fifth of the force he had originally led into Tenochtitlan. The overnight battle—the worst military disaster the conquistadors had suffered in the New World—would go down in Spanish history as La Noche Triste (“The Night of Sorrows”).

The debacle left Cortés with few materiel advantages. Only half of his horses survived, and the column had lost all of its powder, ammunition and artillery and most of its crossbows and harquebuses during the retreat. Yet the Spanish commander managed to hold together his flagging force. Skirting north to avoid a cluster of hostile villages, he headed toward Tlaxcala, home city of his Mesoamerican allies.

Over the days that followed Aztec skirmishers shadowed Cortés’ retreating column, and as the Spaniards neared the Tlaxcalan frontier, the skirmishers joined forces with warriors from Tenochtitlan and assembled on the plain of Otumba, between the conquistadors and their refuge. The trap thus set, on July 7 the numerically superior Aztecs and beleaguered Spaniards met in a battle that should easily have gone in the Mesoamericans’ favor. Again, however, Cortés turned the tables by skillfully using his remaining cavalry to break up the enemy formations. Then, in a daring stroke, he personally led a determined cavalry charge that targeted the enemy commander, killing him and capturing his colors. Seeing their leader slain, the Aztecs gradually fell back, ultimately enabling the conquistadors to push their way through. Though exhausted, starving and ill, they were soon among allies and safe from assault.

One long-standing school of thought on the Spanish conquest attributes Cortés’ success to epidemiological whim—namely that European-introduced smallpox had so ravaged the Aztecs that they were incapable of mounting a coherent defense. In fact, Cortés had defeated many enemies and advanced to the heart of the empire well before the disease made its effects felt. Smallpox arrived in Cempoala in 1520, carried by an African slave accompanying the Narváez expedition. By then Cortés had already defeated an army at Pontonchan; won battles against the fierce, well-organized armies of Tlaxcala; entered the Aztec capital at Tenochtitlan and taken its ruler hostage.

Smallpox had ravaged the populations of Hispaniola and Cuba and indeed had equally disastrous effects on the mainland, killing an estimated 20 to 40 percent of the population of central Mexico. But as horrific as the pandemic was, it is by no means clear that smallpox mortality was a decisive factor in the fall of Tenochtitlan or the final Spanish victory. The disease likely reached Tenochtitlan when Cortés returned from the coast in June 1520, and by September it had killed perhaps half of the city’s 200,000 residents, including Montezuma’s successor, Cuitláhuac. By the time Cortés returned in the spring of 1521 for the final assault, however, the city had been largely free of the disease for six months. The conquistadors mention smallpox but not as a decisive factor in the struggle. Certainly they saw no perceptible drop in ferocity or numbers among the resistance.

On the subject of numbers, some scholars have suggested the conquest was largely the work of the Spaniards’ numerous Mesoamerican allies. Soon after arriving in the New World, Cortés had learned from the coastal Totonac people that the Aztec empire was not a monolithic dominion, that there existed fractures of discontent the conquistadors might exploit. For nearly a century Mesoamericans had labored under the yoke of Aztec servitude, their overlords having imposed grievous taxes and tributary demands, including a bloody harvest of sacrificial victims. Even cities within the Valley of Mexico, the heart of the empire, were simmering cauldrons of potential revolt. They awaited only opportunity, and the arrival of the Spaniards provided it. Tens of thousands of Totonacs, Tlaxcalans and others aided the conquest by supplying the Spaniards with food and serving as warriors, porters and laborers. Certainly their services sped the pace of the conquest. But one cannot credit them with its ultimate success. After all, had the restive tribes had the will and ability to overthrow the Aztecs on their own, they would have done so long before Cortés arrived and would likely have destroyed the Spaniards in turn.

To truly assess the Spanish victory over the Aztecs, one must also consider the internal issues Cortés faced—logistical challenges, the interference of hostile superiors, factional divides within his command and mutiny.

Cortés established coastal Veracruz as his base of operations in Mexico and primary communications link to the Spanish empire. But the tiny settlement and its fort could not provide him with additional troops, horses, firearms or ammunition. As Cortés’ lean command suffered casualties and consumed its slender resources, it required reinforcement and resupply, but the Spanish commander’s strained relations with the governor of Cuba ensured such vital support was not forthcoming. Fortunately for himself and the men of his command, Cortés seems to have possessed a special genius for conjuring success out of the very adversities that afflicted him.

After defeating the Narváez expedition, Cortés integrated his would-be avenger’s force with his own, gaining men, arms and equipment. When the Spaniards lay exhausted in Tlaxcala after La Noche Triste , still more resources presented themselves. Velázquez, thinking Narváez must have things well in hand, with Cortés either in chains or dead, had dispatched two ships to Veracruz with reinforcements and further instructions; both were seized on arrival, their crews soon persuaded to join Cortés. Around the same time two more Spanish vessels appeared off the coast, sent by the governor of Jamaica to supply an expedition on the Pánuco River. What the ships’ captains didn’t know is that the party had suffered badly and its members had already joined forces with Cortés. On landing, their men too were persuaded to join the conquest. Thus Cortés acquired 150 more men, 20 horses and stores of arms and ammunition. Finally, a Spanish merchant vessel loaded with military stores put in at Veracruz, its captain having heard he might find a ready market for his goods. He was not mistaken. Cortés bought both ship and cargo, then induced its adventurous crew to join his expedition. Such reinforcement was more than enough to restore the audacity of the daring conquistador, and he began to lay plans for the siege and recovery of Tenochtitlan.

While the ever-resourceful Cortés had turned these occasions to his advantage, several episodes pointed to an underlying difficulty that had cast its shadow over the expedition from the moment of its abrupt departure from Cuba—Velázquez’s seemingly unquenchable hostility and determination to interfere. Having taken leave of the governor on less than cordial terms, Cortés was perhaps tempting fate by including of a number of the functionary’s friends and partisans in the expedition. He was aware of their divided loyalties, if not overtly concerned. Some had expressed their personal loyalty to Cortés, while others saw him as their best opportunity for enrichment. But from the outset of the campaign still other members of the Velázquez faction had voiced open opposition, insisting they be permitted to return to Cuba, where they would undoubtedly report to the governor. Cortés had cemented his authority among the rebels through a judicious mixture of force and persuasion.

But the problem arose again with the addition of Narváez’s forces to the mix. While headquartered in Texcoco as his men made siege preparations along the lakeshore surrounding Tenochtitlan, Cortés uncovered an assassination plot hatched by Antonio de Villafaña, a personal friend of Velázquez. The plan was to stab the conquistador to death while he dined with his captains. Though Cortés had the names of a number of co-conspirators, he put only the ringleader on trial. Sentenced to death, Villafaña was promptly hanged from a window for all to see. Greatly relieved at having cheated death, the surviving conspirators went out of their way to demonstrate loyalty. Thus Cortés quelled the mutiny.

Whatever advantages the Spaniards enjoyed, victory would have been impossible without his extraordinary leadership

But hostility toward the conquistador and his “unlawful” expedition also brewed back home in the court of Spanish King and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. In Cortés’ absence his adversaries tried every means to undermine him, threatening his status as an agent of the crown and seeking to deny him the just fruits of his labors. The commander was forced to spend precious time, energy and resources fighting his diplomatic battle from afar. Even after successfully completing the conquest, Cortés received no quarter from his enemies, who accused him of both defrauding the crown of its rightful revenues and fomenting rebellion. On Dec. 2, 1547, the 62-year-old former conquistador died a wealthy but embittered man in Spain. At his request his remains were returned to Mexico.

Setting aside long-held preconceptions about the ease of the conquest of Mexico—which do disservice to both the Spanish commander and those he conquered—scholars of the period should rightfully add Cortés to the ranks of the great captains of war. For whatever advantages the Spaniards enjoyed, victory would have been impossible without his extraordinary leadership. As master of the conquest, Cortés demonstrated fixity of purpose, skilled diplomacy, talent for solving logistical problems, far-sighted planning, heroic battlefield command, tactical flexibility, iron determination and, above all, astounding audacity. MH

Justin D. Lyons is an assistant professor in the Department of History and Political Science at Ohio’s Ashland University. For further reading he recommends Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control , by Ross Hassig; The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519–1521 , by Charles M. Robinson III; and Conquest: Cortés, Montezuma, and the Fall of Old Mexico , by Hugh Thomas.

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Celebrating the Legacy of the Office of Strategic Services 82 Years On

From the OSS to the CIA, how Wild Bill Donovan shaped the American intelligence community.

Seminoles Taught American Soldiers a Thing or Two About Guerrilla Warfare

During the 1835–42 Second Seminole War and as Army scouts out West, these warriors from the South proved formidable.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Hernán Cortés Conquered the Aztec Empire

By: Karen Juanita Carrillo

Updated: June 26, 2023 | Original: May 20, 2021

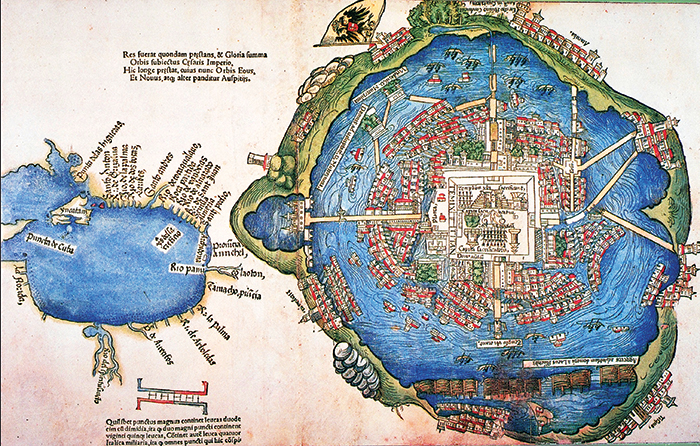

The Aztec Empire , Mesoamerica’s dominant power in the 15th and early 16th centuries controlled a capital city that was one of the largest in the world. Itzcoatl, named leader of the Aztec/Mexica people in 1427, negotiated what has become known as the Triple Alliance —a powerful political union of the city-states of Mexico-Tenochtitlán, Tetzcoco and Tlacopán. As that alliance strengthened between 1428 and 1430 it reinforced the leadership of the Aztecs, making them the dominant Nahua group in a landmass that covered central Mexico and extended as far as modern-day Guatemala.

And yet Tenochtitlán fell into decline after the siege and destruction of the city by the Spanish in 1521—less than two years after Hernándo Cortés and Spanish conquistadors first set foot in the Aztec capital on November 8, 1519. How did Cortés manage to overthrow the seat of the Aztec Empire?

Tenochtitlán: A Dominant Imperial City

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Aztec imperial city in 1519, Mexico-Tenochtitlán was led by Moctezuma II. The city had prospered and was estimated to host a population of between 200,000 and 300,000 residents.

At first , the conquistadors described Tenochtitlán as the greatest city they had ever seen. It was situated on a human-made island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. From its central location, Tenochtitlán served as a hub for Aztec trade and politics. It featured gardens, palaces, temples and raised roads with bridges that connected the city to the mainland.

Other city-states were forced to pay periodic tributes to Tenochtitlán’s public markets and to its religious center, the Templo Mayor or “Great Temple.” Religious tributes sometimes took the form of human sacrifices . While the Aztec’s monetary and religious demands empowered the empire, it also fostered resentment among surrounding city-states.

Hernándo Cortés Makes Allies with Local Tribes

Hernándo Cortés formed part of Spain’s initial colonization efforts in the Americas. While stationed in Cuba, he convinced Cuban Governor Diego Velázquez to allow him to lead an expedition to Mexico, but Velázquez then canceled his mission. Eager to appropriate new land for the Spanish crown, convert Indigenous people to Christianity and plunder the region for gold and riches, Cortés organized his own rogue crew of 100 sailors, 11 ships, 508 soldiers and 16 horses. He set sail from Cuba on the morning of February 18, 1519, to begin an unauthorized expedition to Mesoamerica.

Arriving on the Yucatán coast, Cortés encountered Indigenous people who told him about other Europeans who had been shipwrecked and captured by local Mayans. Cortes freed Jerónimo de Aguilar , a Franciscan friar, from the Mayans and made Aguilar part of his crew. Aguilar turned out to be an invaluable asset to Cortes due to his ability to speak Chontal, the local Mayan language. With Aguilar at his side, Cortés and his conquistadors continued traveling the region, battling Indigenous groups along the way.

Cortés and his men then acquired another asset when an Aztec chief gifted them some 20 enslaved young Mayan women, including Malinalli, a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast. Malinalli became baptized with the Christian name Marina and was later known as La Malinche. La Malinche spoke both the Aztec language of Náhuatl and Mayan Chontal and worked alongside the Spanish invaders, providing the conquistadors with the ability to communicate with any Indigenous groups they encountered.

With La Malinche and Aguilar in tow, the conquistadors made their way to the island city of Tenochtitlán where they were initially welcomed by Emperor Moctezuma II. When Cortés became concerned that Moctezuma's people would turn against his men, he placed Moctezuma under house arrest and Cortés attempted to rule through the detained Moctezuma.

Soon Cortés received word that the Cuban governor had sent a Spanish force to arrest Cortés for insubordination. Leaving his top lieutenant Pedro de Alvarado in charge of Tenochtitlán, Cortés took men to attack the Spanish forces at the coast. Cortes's men defeated the troops and took the surviving Spanish soldiers back with him as reinforcements to Tenochtitlán. In Cortés' absence, Alvarado had hundreds of Aztec nobles killed during a ceremonial feast, leading to further unrest among the Aztec people.

Tenochtitlán residents demanded the Spanish be removed from the city. When the detained Moctezuma could no longer control Tenochtitlán’s residents, the Spaniards either allowed him to die during a skirmish in 1520 or killed him—depending on varying accounts .

Driven from the capital, the Spanish later circled back with a small fleet of ships. Working in alliance with some 200,000 Indigenous warriors from city-states, particularly the Tlaxcala and Cempoala (groups who had resented the Aztec/Mexicas and wanted to see them vanquished), the Spanish conquistadors held Tenochtitlán under siege from May 22 through August 13, 1521—a total of 93 days.

Disease Further Weakens the Aztec

With Tenochtitlán encircled, the conquistadors relied on their Indigenous allies for key logistical support and launched attacks from local Indigenous encampments. Meanwhile, another factor began to take its toll. Unbeknownst to the Spanish, some among their ranks had been infected with smallpox when they had departed Europe. Once these men arrived in the Americas, the virus began to spread—both among their indigenous allies and the Aztecs. (Some research has suggested that salmonella , not smallpox, had weakened the Aztecs.)

The first known case reportedly emerged in Cempoala—one of the city-states that had allied with the Spanish—when an enslaved African came down with the disease. The virus then spread. As the Spaniards and their allies later attacked Tenochtitlán, even when they lost battles, the smallpox virus infected the Aztecs. Aztec troops, members of the noble class, farmers and artisans all fell victim to the disease.

Aztec Aqueducts

The Aztecs built an expansive system of aqueducts that supplied water for irrigation and bathing.

How the Aztec Empire Was Forged Through a Triple Alliance

Three city‑states joined in a fragile, but strategic alliance to wield tremendous power as the Aztec Empire.

Human Sacrifice: Why the Aztecs Practiced This Gory Ritual

In addition to slicing out the hearts of victims and spilling their blood on temple altars, the Aztecs likely also practiced a form of ritual cannibalism.

While many Spaniards had acquired immunity to the disease, the virus was new in the Americas and few Indigenous understood it. The bodies of smallpox victims piled up in the streets of Tenochtitlán and, with the city under siege, there were few available ways to dispose of the bodies.

Spaniards and their allies were taken in as prisoners (the Aztecs tended to hold captured prisoners for sacrifice to the gods, rather than kill them in battle) and traces of the virus were left on the clothes, hair and on dead bodies of those who had had the disease. As Tenochtitlán residents contracted smallpox they had no place to turn for help. Aztec priests and medicinal practitioners knew of no remedy and Tenochtitlán residents had little immunity.

The Spanish Wielded Better Weaponry

The conquistadors arrived in Mesoamerica with steel swords, muskets, cannons, pikes, crossbows, dogs and horses. None of these assets had yet been used in battle in the Americas. The Aztecs fought the Spanish with wooden broadswords, clubs and spears tipped with obsidian blades. But their weapons proved ineffective against the conquistadors’ metal armor and shields.

When the Spanish arrived in the Americas they came from a war-oriented culture that had seen battle against other European nations for dominance and against North Africans for sovereignty. The conquistadors arrived in Mesoamerica with better guns and had been trained in tactical strategies. They deployed a cavalry that could chase down retreating warriors, dogs trained to track down and encircle enemies and horses capable of trampling adversaries.

Up against large armies of Spanish and Indigenous forces, surrounded and cut off from the mainland, and with a population succumbing to an unknown, devastating virus, the Aztec Empire was unable to fight off the invading Spanish conquistadors. The Aztecs, including members of the Aztec royal family—then were forced to adjust to life under Spanish rule.

"Cada Uno En Su Bolsa Llevar Lo Que Cien Indios No Llevarían: Mexica Resistance and the Shape of Currency in New Spain, 1542-1552.” by Allison Caplan, American Journal of Numismatics (1989-), vol. 25, 2013, pp. 333–356. JSTOR .

“Jeronimo de Aguilar,” American Historical Association .

“Aztec Warfare Imperial Expansion and Political Control,” by Ross Hassig, University of Oklahoma Pres s, 1988, p. 244.

“Searching for the Secrets of Nature The Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernández,” by Dora B. Weiner, Stanford University Press , 2000, p. 86.

“Viruses, Plagues, and History Past, Present, and Future,” by Michael B. Oldstone, Oxford University Press , 2020, p. 46.

“So Why Were the Aztecs Conquered, and What Were the Wider Implications? Testing Military Superiority as a Cause of Europe's Pre-Industrial Colonial Conquests,” by George Raudzens. War in History, vol. 2, no. 1, 1995, pp. 87–104. JSTOR . Accessed May 18, 2021.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- HISTORY MAGAZINE

Guns, germs, and horses brought Cortés victory over the mighty Aztec empire

The Aztec outnumbered the Spanish, but that didn't stop Hernán Cortés from seizing Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, in 1521.

After the expedition led by Vasco Núñez de Balboa who crossed Central America to reach the Pacific in 1513, Europeans began to see the full economic potential of this "New World." At first, colonization by the burgeoning new world power, Spain, was centered on the islands of the Caribbean, with little contact with the complex, indigenous civilizations on the mainland.

It was not long, however, before the lure of wealth spurred Spain’s adventurers beyond exploration and into a phase of conquest that would lay the foundations of the modern world. Whole swaths of the Americas rapidly fell to the Spanish crown, a transformation begun by the ruthless conqueror of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés. (See also: New clues to the lost fleet of Cortés .)

Cortés beginnings

Like other conquistadores of the early 16th century, Cortés had already gained considerable experience by living in the New World before embarking on his exploits. Born to modest lower nobility in the Spanish city of Medellín in 1485, Cortés stood out at an early age for his intelligence and his restless spirit of adventure inspired by the recent voyages of Christopher Columbus.

In 1504, Cortés left Spain for the island of Hispaniola (today, home to the Dominican Republic and Haiti), where he rose through the ranks of the fledgling colonial administration. In 1511 he joined an expedition to conquer Cuba and was appointed secretary to the island's first colonial governor, Diego Velázquez.

During these years, Cortés developed the skills that would stand him in good stead in his short, turbulent career as a conquistador. He gained valuable insights into the organization of the islands’ indigenous peoples and proved an adept arbiter in the continual squabbles that broke out among the Spaniards, forever vying to enlarge their estates or snag lucrative administrative positions.

In 1518 Velázquez appointed his secretary to lead an expedition to Mexico. Cortés—as Velázquez was to discover to his cost—was set on becoming a leader rather than a loyal follower. He set off for the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in February 1519 with 11 ships, about 100 sailors, 500 soldiers, and 16 horses. Over the following months Cortés would take matters into his own hands, disobey the governor’s orders, and turn what had been intended to be an exploratory mission into a historic military conquest.

Become a subscriber and support our award-winning editorial features, videos, photography, and much more.

For as little as $2/mo.

Aztec introductions

To the Aztec, 1519 was a year that began with their empire as the uncontested power in the region. Its capital city, Tenochtitlan, ruled 400 to 500 small states with a total population of five to six million. The fortunes of the kingdom of Moctezuma, however, were doomed to a swift and spectacular decline once Cortés and his men disembarked on the Mexican coast. (See also: Rare Aztec Map Reveals a Glimpse of Life in 1500s Mexico. )

Having rapidly imposed control over the indigenous population in the coastal region, Cortés was given 20 slaves by a local chieftain. One of them, a young woman, could speak several local languages and soon learned Spanish too. Her linguistic skills would prove crucial to Cortés’s invasion plans, and she became his interpreter as well as his concubine. She soon came to be known as Malinche, or Doña Marina. The conquistador had a son with her, Martín, who is often regarded as the first ever mestizo—a person of mixed European and American Indian ancestry. (See also: Call the Aztec midwife: Childbirth in the 16th century. )

The news of the foreigners’ arrival soon reached the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma, in Tenochtitlan. To appease the Spaniards, he sent envoys and gifts to Cortés, but he only succeeded in inflaming Cortés’s desires for more Aztec riches. Cortés once described the land near Veracruz, the city he founded on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, as rich as the mythical land where King Solomon obtained his gold. As a mark of his ruthlessness, and to quash any misgivings his crew may have had in disobeying the orders of Governor Velázquez, Cortés ordered the destruction of the fleet he had sailed with from Cuba. There was now no turning back.

Mosaic mask of turquoise and lignite covers a human skull and represents an Aztec god, Tezcatlipoca.

Cortés had a talent for observing and manipulating local political rivalries. On the way to Tenochtitlan, the Spaniards gained the support of the Totonac peoples from the city of Cempoala, who hoped to be freed from the Aztec yoke. Following a military victory over another native people, the Tlaxcaltec, Cortés incorporated more warriors into his army. Knowledge of the divisions among different native peoples, and an unerring ability to exploit them, was central to Cortés’s strategy.

The Aztec had allies too, however, and Cortés was especially belligerent toward them. The holy city of Cholula, which joined with Moctezuma in an attempt to stall the Spaniards, was sacked for two days at Cortés’s command. After a grueling battle lasting more than five hours, as many as 6,000 of its people were killed. Cortés’s forces seemed invincible. In the face of their unstoppable advance, Moctezuma stalled for time, allowing the Spaniards and their allies to enter Tenochtitlan unopposed in November 1519.

Fighting on two fronts

Fear gripped the huge Aztec capital on Cortés’s entry, the chroniclers wrote: Its 250,000 inhabitants put up no resistance to Cortés’s small force of a few hundred men and 1,000 Tlaxcaltec allies. At first Moctezuma formally received Cortés. Seeing the value of the emperor as a captive, Cortés seized him and guaranteed his power over the city.

Establishing a pattern that would recur throughout his career, Cortés soon found himself as much at threat from his own compatriots as from the peoples he was trying to subdue. At the beginning of 1520 he was forced to leave Tenochtitlan to deal with a punitive expedition sent from Cuba by the enraged Diego Velázquez. In his absence, Cortés left Tenochtitlan under the command of Pedro de Alvarado and a garrison of 80 Spaniards.

The hotheaded Alvarado lacked Cortes’s skill and diplomacy. During Cortes’s absence, Alvarado’s execution of many Aztec chiefs enraged the people. After defeating Velázquez’s forces, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan on June 24, 1520, to find the city in revolt against his proxy. For several days, the Spaniards vainly used Moctezuma in an attempt to calm tempers, but his people pelted the puppet king with stones. Moctezuma died a few days later, but his successors would fare no better than he did.

On June 30, 1520, the Spanish fled the city under fire, suffering hundreds of casualties. Some Spaniards died by drowning in the surrounding marshes, weighed down by the vast amounts of treasure they were trying to carry off. The event would come to be known as the Night of Sorrows.

Technology Triumphs

Although the Aztec had the superior numbers, advanced Spanish weaponry ultimately gave them the upper hand. With firearms and steel blades at his disposal, just one Spaniard might annihilate dozens or even hundreds of opponents: “On a sudden, they speared and thrust people into shreds,” wrote one indigenous chronicler, having witnessed the terrifying impact of European arms. “Others were beheaded in one swipe... Others tried to run in vain from the butchery, their innards falling from them and entangling their very feet.”

A smallpox epidemic prevented the Aztec forces from finishing off Cortés’s defeated and demoralized army. The outbreak weakened the Aztec while giving Cortés time to regroup. Spain would win the Battle of Otumba a few days later. Skillful deployment of cavalry against the elite Aztec jaguar and eagle warriors carried the day for the Europeans and their allies.“Our only security, apart from God,”Cortés wrote,“is our horses.”

You May Also Like

He was shipwrecked in Texas in 1528. His unlikely tale of survival became legend

Mass grave found in Fiji sparks a mystery: cannibalism or contagion?

The alleged affair that started a century-long war

Victory allowed the Spaniards to rejoin with their Tlaxcaltec allies and launch the recapture of Tenochtitlan. Waves of attacks were launched on settlements near the Aztec capital. Any resistance was brutally crushed: Many indigenous enemies were captured as slaves and some were even branded following their capture. The sacking also allowed the Spaniards to build up their large personal retinues, taking captives to use as servants and slaves, and kidnapping others for exchanges and ransoms. Growing in number to roughly 3,000 people, this group of captives vastly outnumbered the fighting Spaniards.

Fall of the Aztec

For an assault on a city the size of Tenochtitlan, the number of Spanish troops seemed paltry—just under 1,000 soldiers, including harquebusiers, infantry, and cavalry. However, Cortés knew that his superior weaponry, coupled with the additional 50,000 warriors provided by his indigenous allies, would conquer the city, which was already weakened from starvation and thirst. In May 1521 the Spaniards had cut off the city’s water supply by taking control of the Chapultepec aqueduct.

Even so, the siege of Tenochtitlan was not a given. During fighting in July 1521, the Aztec held strong, even capturing Cortés himself. Wounded in one leg, the Spanish leader was ultimately rescued by his captains. During this setback for the conquistador, the Aztec warriors managed to regain lost ground and rebuild the city’s fortifications, pushing the Spanish onto the defensive for nearly three weeks. Cortés ordered the marshland to be filled with rubble for a final assault. Finally, on August 13, 1521, the city fell.

“Not a single stone remained left to burn and destroy,” one witness wrote. The loss of human life was staggering, both in absolute figures and in its disproportionality. During the siege, around 100 Spaniards lost their lives compared to as many as 100,000 Aztec.

Ladies' Man

According to the chronicler Francisco López de Gómara, Cortés was “very given to women and always gave into temptation.” His biography abounds in romantic entanglements. Throughout his career, Cortés's personal life held a selfish, manipulative streak. In 1514 he married a young Spanish woman named Catalina Suárez, a relative of Governor Diego Velázquez, who soon promoted Cortés after the wedding. But Cortés was not faithful. After the conquest of Mexico, he and Malinche, an Aztec woman who served as his interpreter, had a son together. The marriage to Caralina only ended when she was found dead under mysterious circumstances in 1522. Cortés was suspected of her murder, but nevery charged. Cortés then took as a consort Princess Isabel Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor's daughter. She and Cortés had a daughter, but he later abandoned them. In 1529 Cortés took a Spanish noblewoman, Juana de Zúñiga, as his bride and became a marquis, securing both a high social status and a rather rakish reputation.

The conquest of Tenochtitlan and the subsequent consolidation of Spanish domination over the former Aztec Empire was the first major possession in what became the Spanish Empire. This vast territory would reach its greatest extent in the 18th century, with territory throughout North and South America.

Cortés’s triumph would be short-lived. In just a few years, he would lose many of his lands in the New World. Despite being made a marquis years later, the Conqueror of Mexico did not have a glorious end. In 1547, at the age of 62, he died in a village near Sevilla, Spain, embroiled in lawsuits and his health broken by a series of disastrous expeditions. Decades of rapid expansion in the Americas seemed to have eclipsed his own exploits, and few bells tolled for the man whose ruthlessness and cunning transformed the Americas.

Related Topics

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

- CONQUISTADORES

How old are taxes? Older than you think

These 5 leaders' achievements were legendary. But did they even happen?

The incredible details 'Masters of the Air' gets right about WWII

‘A ball of blinding light’: Atomic bomb survivors share their stories

The truth behind the turbulent love story of Napoleon and Joséphine

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Hernan Cortes: The Conquistador Who Beat the Aztecs

- Read Later

Hernan Cortes was a Spanish conquistador who lived between the 15th and 16th centuries AD. He is best remembered for his expedition against the Aztec Empire centered in Mexico. This was part of the first phase of Spain’s expansion into the New World. Hernan Cortes’ expedition resulted in the collapse of the Aztec Empire, and the control of a large part of modern-day Mexico by the Spanish Empire. On the one hand, Cortes is regarded as a heroic character who contributed greatly to the Spanish Empire. On the other hand, he is perceived as a villain whose murderous actions caused the downfall of a sophisticated civilization.

The Early Life of Hernan Cortes

Hernan Cortes was born in 1485 in Medellin, a village in the province of Badajoz, Extremadura , Spain. At that time, Cortes’ place of birth was part of the Kingdom of Castile . Cortes’ father was Martin Cortes de Monroy, an infantry captain, whilst his mother was Catalina Pizarro Altamirano. Cortes’ family belonged to the lesser nobility, though they were by no means wealthy. Incidentally, through his mother, Cortes was a second cousin of Francisco Pizarro, another conquistador who gained fame from his expedition in the New World.

- Becerrillo: The Terrifying War Dog of the Spanish Conquistadors

- Conquistadors caused Toxic Air Pollution 500 years ago by changing Incan Mining

At the age of 14, Cortes was sent to study at the University of Salamanca . This was Spain’s foremost center of learning at the time. Although it is unclear what Cortes studied at the university, it is assumed that he studied Law, and perhaps Latin. It seems that Cortes’ parents were hoping that their son would embark on a legal career, which would have made him wealthy. Unfortunately, Cortes returned to Medellin after spending two years at Salamanca, as studying was probably not his strong point. Although Cortes did not finish his studies, his time at Salamanca did help him familiarize himself with the legal codes of Castile, which would come in handy later in his life.

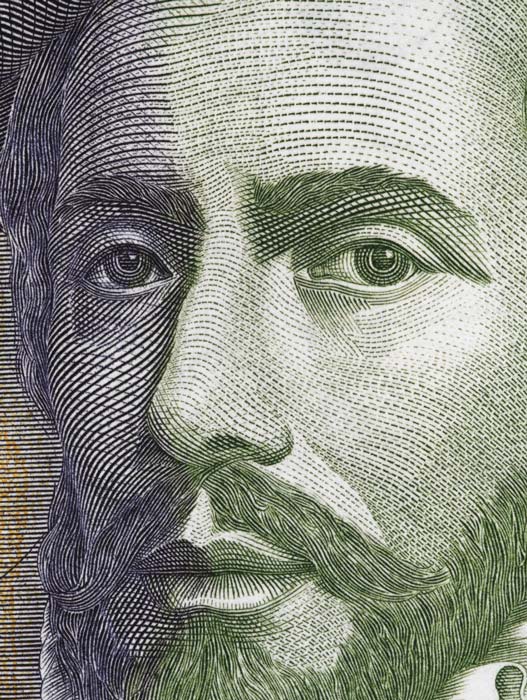

Hernan Cortes portrait on a Spanish 1000 peseta note from 1992. (vkilikov / Adobe Stock)

Cortes’ return to Medellin was not exactly a change for the better for the future conquistador. As Medellin was only a small village, it would have been a rather stifling place for the ambitious young man. Around the same time, Christopher Columbus was making his voyages to the New World, and news of his exciting discoveries would have certainly reached the ears of Cortes and his parents, who recognized that Cortes might be able to make a name for himself in these newly discovered lands.

Therefore, in 1502, arrangements were made for Hernan Cortes to sail to the New World with Nicolas de Ovando, the newly appointed governor of Hispaniola , and a family acquaintance.

Cortes, however, was not destined to be part of this voyage. Before he could even set sail, Cortes sustained an injury whilst escaping from the bedroom of a married woman in Medellin. Consequently, he had to take some time to recover from his injury, after which, he spent a while wandering around Spain.

Cortes did manage to sail to the New World in 1503, as part of a convoy of merchant ships headed to the capital of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo. Cortes was on a ship commanded by Alonso Quintero, who attempted to deceive his superiors. Quintero did so to reach the New World first, and to secure personal advantages. It is suggested that Quintero’s actions might have been a model for Cortes’ own treacherous behavior when he became a conquistador later on.

In any case, this was still many years before Cortes became the man who conquered the Aztec Empire . When he arrived in Santo Domingo, Cortes registered himself as a citizen, which gave him the right to a building plot, and some land for cultivation. As de Ovando was still the governor at that time, he gave Cortes a repartimiento (corvée labor) of natives and made him a notary of the town of Azuza. Thus, over the next couple of years, Cortes slowly established himself in Hispaniola.

Portrait of Diego Velasquez de Cuellar, who led the expedition to Cuba in which Hernan Cortes was given a chance to prove his spirit. (John Carter Brown Library / Public domain )

Hernan Cortes’ Expedition to Cuba

In 1511, Cortes joined the expedition to conquer Cuba . The expedition was led by Diego Velazquez de Cuellar, an aide to the governor of Hispaniola. Velazquez, who became the governor of Cuba, was so impressed by Cortes that he gave him a high position in the colonial administration.

- The Stolen Treasure of Montezuma

- Test Show’s Aztec Gold Bar Was Lost By Fleeing Conquistadors

Although Cortes and Velazquez were initially on good terms, the relationship between the two men deteriorated over time. For instance, Cortes was jailed twice by the governor, but succeeded is escaping on both occasions. Nevertheless, Cortes earned a reputation for being daring and bold. Moreover, following Cortes’ marriage to Catalina Xuarez, Velazquez’s sister-in-law, relations between the two men improved.

In 1518, Velazquez and Cortes signed an agreement, which placed the latter in command of an expedition to explore the coast of Mexico . Cortes was to initiate trade with the indigenous people he met during his voyage. It has been suggested that the governor wanted Cortes to only engage in trade, so that he could have the privilege to conquer the indigenous people himself later.

Cortes, however, used the legal knowledge he gained during his days at Salamanca to insert a clause in the agreement that would allow him to take necessary emergency measures without Velazquez’s prior approval if they profited Spain.

Although Velazquez had earlier commissioned another expedition to explore the Mexican coast, Hernan Cortes’ was much bigger. This earlier one, led by the governor’s nephew, consisted of four ships, whereas Cortes assembled a fleet of 11 ships. About half of Cortes’ expedition was financed by Velazquez. Cortes himself went into debt as a result of borrowing additional funds for the expedition, when his own assets went dry. The financial commitment of both men showed that they were both keenly aware that the conquest of Mexico would bring them great fame, fortune, and glory.

It was also this awareness that made Velazquez suspicious that Cortes would betray him, conquer Mexico on his own, and establish himself as governor of the newly conquered land. Therefore, the governor decided to replace Cortes with someone he had more faith in.

Luis de Medina was sent with Velazquez’s orders to replace Cortes. Unfortunately for de Medina, he was intercepted, and killed by Cortes’ brother-in-law. When Cortes heard the news, he sped up the preparations for his expedition. On the 18 th of February 1519, Cortes was about to set sail, when Velazquez himself arrived at the dock, in one last attempt to revoke the conquistador’s commission. Cortes, however, ignored the governor, and hurriedly sailed off.

This old painting by an unknown artist shows the entrance of Hernan Cortes into the city of Tabasco on the Yucatan. ( Public domain )

Before Attacking the Aztecs, Cortes Visits the Yucatan

Prior to arriving on the mainland, Cortes spent some time on the island of Cozumel , where he heard stories of other white men living in the Yucatan. It turns out that there were two Spaniards, Geronimo de Aguilar, and Gonzalo Guerrero living amongst the Maya . These two were survivors of a shipwreck in 1511.

Whilst Guerrero chose to continue living with the Maya, de Aguilar, who was a Franciscan priest, joined Cortes’ expedition. During his time with the Maya, de Aguilar picked up Yucatec Mayan, as well as a few other Mesoamerican languages, which made him valuable as a translator.

Geronimo de Aguilar, however, was not the only translator on Cortes’ expedition. Shortly after leaving Cozumel, the expedition landed at Potonchanon, on the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula . It was here that Cortes found his second translator, a woman whom Cortes referred to as Dona Marina, and known also as Malintzen, or La Malinche.

The story of Malintzen’s early life is unclear, though it is generally accepted that she was born into a family but was enslaved as a child. It is believed that during her slavery, Malintzen was sold several times, which brought her to different parts of the Yucatan Peninsula. As a result of her forced travels, Malintzen became fluent in both Yucatec and Nahuatl, the latter being the language of the Aztecs, and a lingua franca of the area.

When Cortes arrived in Potonchanon, he was given 20 enslaved women, one of whom was Malintzen, as a peace offering. The women were forced to join the expedition and were baptized as Catholics. Malintzen’s linguistic skills were soon recognized, and she was paired with de Aguilar. Initially, Cortes would speak to de Aguilar in Spanish, who would translate it into Yucatec. Malintzen would then translate this into Nahuatl, thereby enabling Cortes to speak with the natives.

Eventually, Malintzen learned Spanish as well, which allowed her to communicate directly between Cortes and the Aztecs he met without de Aguilar as an intermediary. Malintzen, however, was more than just an interpreter, and played a significant role in Cortes’ conquest of the Aztec Empire. For instance, Malintzen was instrumental in helping Cortes to form alliances with tribes that were eager to overthrow their Aztec overlords. Malintzen also uncovered plots against the Spanish, who foiled them before any serious harm could be done. Thus, Malintzen was addressed by Cortes’ men with the title Dona, meaning “Lady.”

It was on this Veracruz, Mexico beach (where the Quiahuiztlan archeological site stands today) that Hernan Cortes landed his Mexican expedition in 1519 and scuttled his fleet to ensure maximum motivation for his soldiers. (Gengiskanhg / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Hernan Cortes Attacks the Aztecs from Veracruz, Mexico

After a few months in the Yucatan, Cortes continued his journey westward, and founded the settlement of La Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz (modern-day Veracruz). Cortes got himself elected as captain-general of the new settlement, which freed him from the authority of Velazquez. It was from this settlement that Cortes began his campaign to conquer the Aztec Empire. Initially, the Aztecs did not see the Spanish as a threat. In fact, their ruler, Moctezuma II sent emissaries to present gifts to these foreign strangers. This, however, did little to change the minds of the Spanish. As a matter of fact, Cortes had all but one of his ships scuttled, which meant that he and his men would either conquer the Aztecs Empire or die trying.

As Cortes marched towards Tenochtitlan , the Aztec capital, he made alliances with the local tribes, one of the first being the Tlaxcalans, who were bitter enemies of the Aztecs. Following the Massacre of Cholula in 1519, more tribes decided to submit to the Spanish, fearing that they would suffer the same fate as the Cholulans if they refused.

In any event, when Cortes and his men arrived in Tenochtitlan, he was warmly welcomed by Moctezuma. It seems that the emperor intended to learn more about the Spanish, especially their weaknesses, so that he could crush them later. Cortes, however, found out about Moctezuma’s plot, and took the emperor hostage, believing that this would stop the Aztecs from attacking him and his men.

In the meantime, an expedition under Panfilo de Narvaez was sent in 1520 by Velazquez to relieve Cortes of his command, capture the renegade conquistador, and bring him back to Cuba to be tried. When he heard of the expedition, Cortes took some of his men, and launched a surprise night attack on de Narvaez’s much larger army, thereby defeating it.

After this victory, he hurried back to Tenochtitlan, as the situation there was quite tense as well. During Cortes’ absence, the Spanish in the city had killed many Aztec nobles during a religious festival, which led to them being besieged in Moctezuma’s palace. When Cortes returned, he decided that the best course of action was to retreat from Tenochtitlan.

The decision to retreat was in part caused by the death of Moctezuma. According to one version of the story, Moctezuma was killed by the Spanish after they realized he had outlived his usefulness. According to another account, the emperor was pelted with stones when he tried to speak to his subjects from a balcony and died of his wounds.

Whilst the Cortes were crossing the causeway to the mainland, his rear guard was attacked by the Aztecs, and he lost many men. This episode became known as La Noche Triste, or “The Night of Sorrows.”

Spanish conquistador, Hernan Cortes, as he must have looked towards the end of his life by an unknown artist. (Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando / Public domain )

Cortes Takes The Aztec Capital And Moves On

In spite of this victory, the Aztecs had not crushed the Spanish, and Cortes, having regrouped his men, returned to Tenochtitlan in 1521, besieged the city, and captured it. Although the fall of Tenochtitlan made Cortes the conqueror of the Aztec Empire, in reality the Spanish took many more years to conquer the rest of Mesoamerica.

- The Many Burials of Hernan Cortes: Locating the Gravesite of a Conquistador

- Will The Lost Fleet of Hernán Cortés And Its Treasures of the Aztec Finally be Found?

In any case, Cortes’ achievement, as well as all the treasures he brought back to Spain, made him a very popular man when he returned home. At the same time, there were also those who were jealous of Cortes’ success, and sought to bring him down. In 1528, Cortes returned to Spain to seek justice from the Spanish king, Charles V. He succeeded in convincing the king and was rewarded for his efforts in Mexico.

Cortes returned to Mexico in 1530 with new titles, but his powers were reduced. Cortes stayed in Mexico till 1541, and led several expeditions, though these are much less celebrated than his conquest of the Aztec Empire.

In 1541, Cortes returned to Spain, and was part of the expedition against Algiers. In 1547, Cortes decided to return to Mexico, but died whilst he was in Seville on the 2 nd of December that year.

His remains were moved several times, before their location was lost, only to be rediscovered in Mexico City during the 20 th century.

Top image: Hernan Cortes burning his ships to motivate his men as they begin to tackle the Aztec Empire from their base in Veracruz, Mexico. Source: joserpizarro / Adobe Stock

By Wu Mingren

American Historical Association, 2021. Jeronimo de Aguilar. [Online] Available at: https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-...

History.com Editors, 2019. Hernan Cortes. [Online] Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/exploration/hernan-cortes

Innes, R. H., 2021. Hernán Cortés. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hernan-Cortes

New World Encyclopedia, 2017. Hernán Cortés. [Online] Available at: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hern%C3%A1n_Cort%C3%A9s

Szalay, J., 2018. Hernán Cortés: Conqueror of the Aztecs. [Online] Available at: https://www.livescience.com/39238-hernan-cortes-conqueror-of-the-aztecs....

The BBC, 2014. Hernando Cortés (1485-1547). [Online] Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/cortes_hernan.shtml

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2021. Montezuma II. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Montezuma-II

Women & the American Story, 2021. Life Story: Malitzen (La Malinche). [Online] Available at: https://wams.nyhistory.org/early-encounters/spanish-colonies/malitzen/

Wu Mingren (‘Dhwty’) has a Bachelor of Arts in Ancient History and Archaeology. Although his primary interest is in the ancient civilizations of the Near East, he is also interested in other geographical regions, as well as other time periods.... Read More

Related Articles on Ancient-Origins

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

History Hit Story of England: Making of a Nation

How Did Hernán Cortés Conquer Tenochtitlan?

Sarah Roller

14 jan 2021, @sarahroller8.

On 8 November 1519, Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés reached Tenochtitlan – capital of the Aztec Empire. It would prove to be an era-defining moment, signalling the beginning of the end for the American continent’s great civilisations, and the start of a new and terrible age.

Starting afresh in the New World

Like many men who set off to explore distant lands, Cortés was not a success back at home. Born in 1485 in Medellín, the young Spaniard was a disappointment to his family after quitting school early and allegedly badly injuring himself whilst escaping out of the window of a married woman.

Bored of his small-town life and distant family, he left for the New World in 1504 aged just just 18, and settled in the newly created colony of Santo Domingo (now in the Dominican Republic.) Over the next few years, he caught the eye of his colonial masters as he took part in expeditions to conquer Hispaniola (Haiti) and Cuba.

With Cuba newly conquered by 1511, the young adventurer was rewarded with a high political position on the island. In typical fashion, relations between him and the Cuban governor Velazquez began to sour over Cortes’ arrogance, as well as his rakish pursuit of the governor’s sister-in-law.

Eventually, Cortés decided to marry her, thus securing the good will of his master, and creating a newly wealthy platform for some adventures of his own.

An illustration of Emperor Moctezuma welcoming Cortés to Tenochtitlan.

Into the unknown

By 1518, many of the Caribbean islands had been discovered and colonised by Spanish settlers, but the great uncharted mainland of the Americas remained a mystery. That year Velazquez gave Cortés permission to explore the interior, and though he quickly revoked this decision after another squabble, the younger man decided to go anyway.

In February 1519 he left, taking 500 men, 13 horses and a handful of cannon with him. Upon reaching the Yucatan peninsula, he scuttled his ships. With his name now blackened by the vengeful governor of Cuba, there would be no going back.

From then on Cortés marched inland, winning skirmishes with natives, from whom he captured a number of young women. One of them would one day father his child, and they told him of a great inland Empire stuffed with staggering riches. In what is now Veracruz, he met with an emissary of this nation, and demanded a meeting with the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma.

A 19th century portrait of Hernan Cortés by Jose Salome Pina. Image credit: Museo del Prado / CC.

Tenochtitlan – the island city

After the emissaries haughtily refused him many times, he began to march onto the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan – refusing to take no for an answer. On the way there he met with other tribes under the yoke of Moctezuma’s rule, and these warriors quickly swelled the Spanish ranks as the summer of 1519 went slowly by.

Finally, on 8 November, this ragtag army arrived at the gates of Tenochtitlan, an island city said to have been astonishingly rich and beautiful. Seeing this host at the gates of his capital, Moctezuma decided to receive the strange newcomers peacefully, and he met with the foreign adventurer – who was basking in the local belief that this strange armoured man was actually the serpent God Quetzalcoatl.

The meeting with the Emperor was cordial, and Cortés was given large amounts of gold – which was not seen to be as valuable to the Aztecs. Unfortunately for Moctezuma, after coming all this way the Spaniard was fired up rather than placated by this show of generosity.

Cortés’ bloody road to power

While in the city he learned that some of his men left by the coast had been killed by locals, and used this as a pretext to suddenly seize the Emperor in his own palace and declare him to be a hostage. With this powerful pawn in his hands, Cortés then effectively ruled the city and its Empire for the next few months with little opposition.

This relative calm did not last long. Velazquez had not given up on finding his old enemy and dispatched a force which arrived in Mexico in April 1520. Despite being outnumbered, Cortés rode out of Tenochtitlan to meet them and incorporated the survivors into his own men after winning the ensuing battle.

In a vengeful mood, he then marched back to Tenochtitlan – in his absence, his second-in-command, Alvarado, had ordered the killing of hundreds of Aztec people after they attempted to perform a ritual human sacrifice as part of their celebrations for the festival of Toxcatl. Shortly after Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan, Moctezuma was killed. Despite claiming that it had happened in an uncontrollable riot, historians have suspected foul play ever since.

As the situation in the city escalated terribly, Cortés had to flee for his life with a few of his men on what is now known as La Noche Triste: in his confidence, he had underestimated the Aztecs, failed to understand their tactics and overestimated the ability of his own troops. He lost 870 men, a significant percentage of the Spanish forces in Mexico, as a result.

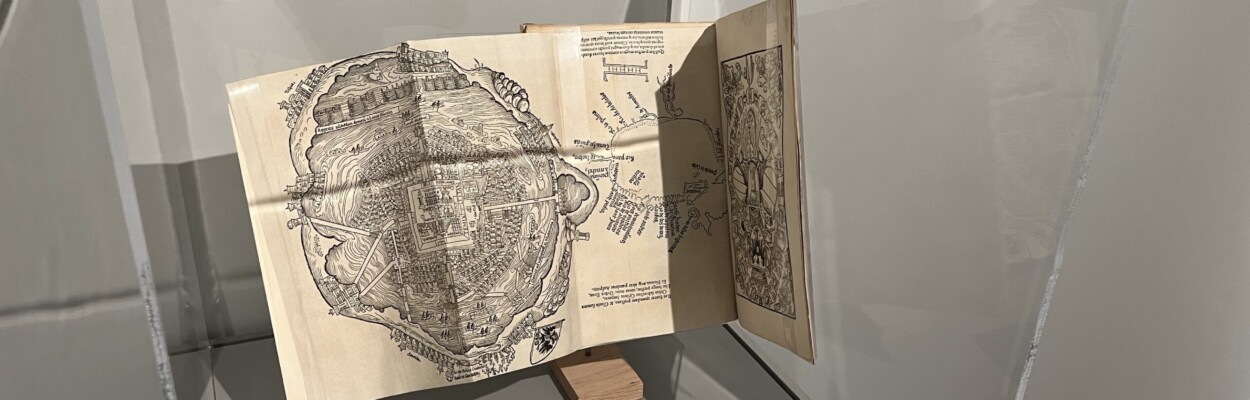

A depiction of the founding of Tenochtitlan taken from the Codex Mendoza, a 16th century Aztec codex.

After forming alliances with local rivals, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan and besieged the city, almost razing it to the ground, and claiming it for Spain under the name of Mexico City. With no one to tell him otherwise, he then ruled as the self-styled governor of all Mexico from 1521-1524.

Cortés’ legacy

In the end, Cortés got what he probably deserved. His demanding of recognition and wilful arrogance gradually alienated the King of Spain, and when the ageing explorer returned to the Royal court he met with a chilly reception.

Cortés retired back to Mexico, where he spent time on his extensive states, as well as engaging in some Pacific exploration: he is credited with the Western ‘discovery’ of the Baja California peninsula.

He eventually died, embittered, in 1547, having left behind a legacy of European empire-building in the Americas, and wiped a powerful civilisation off the face of the earth.

You May Also Like

How a find in Scotland opens our eyes to an Iranian Empire

Do you know who built Petra?

The Dark History of Bearded Ladies

Did this Document Legitimise the Yorkists Claim to the Throne?

The Strange Sport of Pedestrianism Got Victorians Hooked on Coca

Puzzle Over These Ancient Greek Paradoxes

In Ancient Rome, Gladiators Rarely Fought to the Death

Archaeologists Uncover Two Roman Wells on a British Road

Young Stalin Made His Name as a Bank Robber

3 Things We Learned from Meet the Normans with Eleanor Janega

Reintroducing ‘Dan Snow’s History Hit’ Podcast with a Rebrand and Refresh

Don’t Try This Tudor Health Hack: Bathing in Distilled Puppy Juice

World History Edu

- Famous Explorers / Spanish History

Hernán Cortés: History, Life, Accomplishments, & Atrocities Committed

by World History Edu · February 5, 2020

Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés – Life and Accomplishments

Most known for invading Mexico and defeating the Aztec Empire in 1521, Hernán Cortés was a Spanish nobleman and famous explorer who helped expand the Empire of Spain into the New World. Why and how did this conquistador vanquish the Aztecs – one of history’s greatest civilizations? Here is everything that you need to know about the life story and accomplishments of Hernán Cortés.

Hernán Cortés was born in Medellín, Spain, to a family of not so much renowned nobility. Growing up, Cortés was not the strongest of children. Regardless of that he was quite intelligent for his age.

When he was 14, his parents sent him to study Latin at his uncle’s school in Salamanca. Two years into his studies, Cortés abandoned the course and went back home. His decision to abandon school was primarily influenced by news of famed explorer Christopher Columbus’ expeditions into the New World.

Cortés desired nothing than to follow in Columbus’s footstep and become a renowned explorer and Spanish conquistador.

Expeditions to Haiti and Cuba

Cortés’s maiden voyage to the Americas occurred in 1504. He sailed for Hispaniola (modern day Haiti and Dominica Republic). Aged around 19, Cortés arrived in Santo Domingo in 1504. Santo Domingo was the capital of Hispaniola. In the city, he had brief educational spells training to become a lawyer. The late teenager spent the next seven years of his life in Hispaniola. He worked as notary official. Sometimes, he worked on the farm.

In 1511, he signed up to the crew of famous Spanish explorer Diego Velázquez’s expedition to Cuba. While in Cuba, he served as a treasury assistant to Governor Nicolás de Ovando.

For his contribution to the conquest of Cuba, he was rewarded with large parcels of land and Indian slaves. As the years rolled by, Cortés became an influential person in Cuba. He was particularly close to the governor of Cuba, Diego Velázquez. He served as Velázquez’s lieutenant.

Expedition to Mexico

In 1518, Cortes was able to convince Velázquez to let him lead an expedition into Mexico. Velázquez accepted his request and gave Cortés his blessings.

Just a few months before Cortes’s expedition, Velázquez had a change of mind. However, the brave and daring Cortés refused to back down. He proceeded and sailed to Mexico with about 11 ships and over 500 men.

Cortés’s mutiny against the governor of Cuba was not uncommon. Early Spanish colonization of the Americas was rife with mutinies and betrayals. For example, the ship that Cortes boarded on his maiden voyage to the Americas had a captain (Alonso Quintero) who mutinied against his superiors.

In 1519, Cortés’s crew of explorers arrived at place called Yucatan, off the Mexican coast. Looking for wealth and glory, Cortés consistently disobeyed Velázquez’s order to come back home. In addition to fame and glory, Cortés had it at the back of his mind to roll out a massive conversion exercise of the natives to Catholicism.

A month after his arrival at Yucatan, Cortés and his men seized the territory in the name of the Spanish Empire. Along the way, he also engaged in a number of battles with native tribes. He and his priests also converted some of the natives into Christianity. Many of those converts were forced into the faith. Also, he encouraged his men to pillage the land and abuse the conquered natives.

Cortés had several illegitimate children with native Indian women. For example, he and La Malinche had a child called Martín (El Mestizo). After a brief period of time, she learned Spanish. For most part of the time, Malinche served as his interpreter. Her usefulness came in the fact that she was reasonably fluent in Aztec and Mayan languages.

Veracruz Settlement

A few months into his stay on the continent, Cortés proceeded west and established a settlement called, Veracruz. He took some of the locales as his allies. In spite of this, it did not stop Cortés from thinking the indigenous people as culturally and religiously inferior to the Spanish. It was not uncommon for Spanish explorers to have this notion about the natives. They found the practice of human sacrifices by the natives particularly abhorrent.

In September, 1519, he briefly clashed with the Otomis and the Tlaxcalans. In the end, some of those indigenous people later allied with Cortés.

After claiming Veracruz for himself, under the Crown’s name, Cortés destroyed his ships. The rationale behind this was to prevent his men from sailing back. His men, therefore, had only one option – march into the heart of the Aztec Empire, Tenochtitlán.

Invasion of the Aztec Empire

Hernando Cortés invades Tenochtitlan, the Capital of the Aztec Empire, in 1521 | Image: Britannica.com

Cortes first met officials of the Aztec Empire at San Juan de Ulúa in spring 1519. On several occasions he asked for a meeting with Moctezuma II, the ruler ( tiatoani ) of the Aztecs. The Aztecs refused to have any meeting.

In August 1519, Cortes, along with about 600 men, headed for the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan. He was also in the company of several hundreds of local tribe men from the Totonacs and the Nahuas.

On his way to Tenochtitlán, he killed several thousands of unarmed noblemen and civilians in Cholula in 1519. His men also burned down a great portion of the city.

In November 1519, Cortes was received by Moctezuma II. The Spanish explorer was given a warm welcome and Cortes entered the city unimpeded. Many say the emperor did this in order to learn the weaknesses of the invading force. However, some historians believe that some Aztecs regarded Cortés as a messenger of the god Quetzalcoatl – the feathered serpent deity of the Aztecs.

Owing to this fascination, Moctezuma dashed Cortés several ounces of gold and other gifts. Consumed by greed, Cortés decided to take Moctezuma hostage.

Why did Hernán Cortés take Moctezuma hostage?

First of all, some historians say that what prompted Hernán Cortés to hold the ruler of the Aztecs hostage was because Cortés received news that some Aztecs had attacked his men. The second and more likely reason is that Cortés wanted more gold for himself.

In 1520, Governor Veláquez sent a number of ships, which were under the command of Pánfilo de Narváez, to relieve Cortés of his command in Mexico. Narváez sailed to Mexico with about a thousand men. While Cortes held Tenochititlán as a prisoner, Cortés was able to rule the entire Aztec people.

Cortés captures Tenochtitlán