Home Visit Network

Pros & Cons of Home Visits - Patients and Clinicians

Striking a Balance: The Mutual Benefits and Challenges of In-Home Health Care in Australia's Allied Health Sector

In allied health, the challenge is to meet the demand for services. Australia’s 195,000 allied health professionals deliver an estimated 200 million health services annually. The allied health workforce is increasing rapidly as demand grows across the aged care and disability sectors.

To cater for an aging population many allied health professionals prefer to provide direct health care services to patients in their own homes, providing high quality services which are amongst the best in the world.

- No more making appointments

- No more waiting rooms

- No more driving loved ones across town

As with every choice in life, there are pros and cons for both the patient and their clinician. Fortunately, the pros far outweigh any previous challenges faced by either party. Today’s allied health providers can visit the homes of their patients and provide high-quality care when it is needed.

Why Home Health Care is Necessary

When recovering from an injury or simply dealing with an aging body, keeping patients comfortable and feeling as capable as possible is essential. For many, mobility restrictions drive patients in the direction of home-based care, providing comfort and safety in familiar surroundings. Allied Health professionals are trained and capable of helping patients and their loved ones learn more about the types of exercises and treatments they need. They also help with making adjustments to accommodate changes in mobility and health. Working with an allied health professional in the home helps patients become more confident in their day to day activities. It also helps focus on the fact that what they are doing is based on a plan that was created specifically for them – not for patients in general.

PROS of PATIENTS utilising home health care

1. No waiting times. On any given day, therapists may not be sure what services they’ll be performing, leading to extended waiting times for their next patient. A home visit eliminates the inconvenience of not only travel time, but unexpected waiting room blow outs. 2. Less Exposure to outside elements. Reducing the risk of coming into contact with seasonal diseases or Covid- 19. No need to sit in a waiting room social distancing, not knowing if others have been exposed to, or infected with Covid-19, and are not yet symptomatic. 3. Family members are involved in care. When an allied health professional visits and treats a patient in their home, others can be present. Instead of being surrounded by clinicians in a medical facility, patients know that someone they explicitly trust can help to monitor the care being received. 4. One on one care is provided. Patients who receive home health care know that the professional they see is focused entirely on them during each session. 5. Staying home is easier. For people with mobility issues, even getting to appointments can be a challenge. 6. In-home health care allows patients to practice immediately. Doing an exercise in a wide-open space is one thing. Being able to utilise actual permanent surroundings is another thing entirely. By holding physical therapy sessions in a patients home, the therapist is able to demonstrate exactly what patients can do in the home for themselves, and how it should be done. 7. Cost effective. Home health care is recognised by most health providers as being more cost effective than traditional inpatient care, when comparing average payments across setting such as skilled nursing facilities, inpatient residential facilities, and long-term care hospitals. 8. Modern Technology. Dedicated websites give you access to all local in home services. Eftpos payments and Medicare rebates are all available via mobile phone apps.

CONS of PATIENTS utilising home health care

1. Increased stress levels. Home is where a person should feel most comfortable. Sometimes having an outside influence enter it can cause people to feel uncomfortable and as if they are losing their independence. To overcome this, it’s important to remind patients that while they do in fact have people coming into their home, this is being done in order to ensure that they can remain at home for as long as possible. 2. The environment won’t be as structured as it would be in a facility. Sometimes home health care takes away the ability for the therapist to utilise all available tools. For example, equipment that won’t fit into a car, requiring a more thoughtful way to structure the sessions to meet needs. 3. A patient’s conditions or needs may not be met with what is available in the home. What works for one individual may not work for another. One common solution is to commence treatment outside of the home and when the condition has improved, re-evaluate and assess if home care has become a viable option.

PROS of CLINICIANS utilising home health care

1. Self-employment opportunities. Work when you want… Part time, full time, weekends, Work around your normal hours of employment and build up your personal patient base. Take time off for the school pick up, school holidays, personal time, even holidays. 2. No down time. Unlike a clinical situation with gaps between appointments or “no shows”, all your patients are at home and therefore flexible when you attend. 3. Small overheads. None of the necessary overheads running a clinic… No rent, no electricity, no staff, no office furniture. 4. Virtual office. Book appointments, access and write medical notes, online accounting, submit Medicare/DVA claims, promote your services on social media, all without having to pay staff. 5. Mobile phone banking. Instant payment through Tap and Go using phone apps, send and receive faxes, and perhaps, best of all… Google maps!

CONS of CLINICIAN’S utilising home health care

1. Longer visits. Compared to the clinical environment, care for patients at home requires longer visits. Home- based care practitioners see, on average, just five to seven patients a day. 2. Clinical safety. There are specific risks to clinician’s safety in the home setting. These include: environmental hazards such as infection control, sanitation, and physical layout. Difficulty of balancing patient autonomy and risk, and the different needs of patients receiving home based care. Clinicians are understandably disinclined to visit homes in areas with high rates of crime. Some mobile apps provide access to immediate emergency response through a “panic button” used by home-based care teams. 3. Lack of supporting infrastructure. There should be clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to assess the suitability of a home-based solution. Medical schools must prepare the next generation of health providers for the inevitable shift from hospital to home by integrating home-based care into required curriculum and training. Some programs are already taking this step. For example, the John Hopkins University School of Medicine in the USA significantly increased residents’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes relevant to home-base care. Such programs can address the shortage of allied health carers trained in home-based care and fill the gaps in medical education about caring for frail and vulnerable patients. Staying at Home or Home Alone?

Many seniors prefer to remain in their own home for as long as possible, They don’t see themselves as needing support or assistance, even if they do struggle more than they used to. Whether your loved one is at home by circumstance or choice, you worry about their health and safety. Even the most independent seniors may have a bit of trouble getting around as the body slows down. The fact remains: Most older people could use a helping hand. If you have a loved one you’re caring for or concerned about, the Home Visit Network’s directory of in-home services is a great solution.

Subscription

Pick the newsletters you'd like to receive

Search with Tags

Popular posts.

Unlocking the Benefits of Mobile Occupational Therapy for Elderly Care

04 Aug 2023 Home Visit Network

Mobile Occupational Therapy: A Pathway to Independence and Enhanced Quality of Life

Revolutionizing Healthcare: How Mobile Occupational Therapy is Shaping the Future

22 May 2023 Home Visit Network

Bridging the Gap, One Home at a Time

A Guide to Mobile Speech Pathology for Children

04 Oct 2023 Home Visit Network

Empowering Communication: Mobile Speech Pathology's Transformative Journey

Subscribe to our newsletter

We're committed to your privacy. Home Visit Network uses the information you provide to us to contact you about our relevant content, products, newsletters and services.

5 Obstacles to Home-Based Health Care, and How to Overcome Them

by Pooja Chandrashekar , Sashi Moodley and Sachin H. Jain

Summary .

One of the most promising opportunities to improve care and lower costs is the move of care delivery to the home. An increasing number of new and established organizations are launching and scaling models to move primary, acute, and palliative care to the home. For frail and vulnerable patients, home-based care can forestall the need for more expensive care in hospitals and other institutional settings. As an example, early results from Independence at Home, a five-year Medicare demonstration to test the effectiveness of home-based primary care, showed that all participating programs reduced emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions for homebound patients, saving an average of $2,700 per beneficiary per year and increasing patient and caregiver satisfaction. There are tremendous opportunities to improve care through these home-based care models, but there are significant risks and challenges to their broader adoption.

One of the most promising opportunities to improve care and lower costs is the move of care delivery to the home. An increasing number of new and established organizations are launching and scaling models to move primary, acute, and palliative care to the home. For frail and vulnerable patients, home-based care can forestall the need for more expensive care in hospitals and other institutional settings. As an example, early results from Independence at Home , a five-year Medicare demonstration to test the effectiveness of home-based primary care, showed that all participating programs reduced emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions for homebound patients, saving an average of $2,700 per beneficiary per year and increasing patient and caregiver satisfaction.

Partner Center

Revisiting Home Visiting: Summary of a Workshop (1999)

Chapter: challenges faced by home visiting programs, challenges faced by home visiting programs.

The workshop participants identified several critical challenges that face virtually all home visiting programs. They include family engagement, staffing, cultural and linguistic diversity, and conditions, such as maternal depression, that are experienced by many of the participating families.

Family Engagement

The engagement of families in home visitation programs includes the combined challenges of getting families to enroll, keeping them in the program, and sustaining their interest and commitment during and between visits. Parental engagement is essential to the effectiveness of programs and to the validity of research efforts. For example, ongoing reanalyses conducted by Margaret Burchinal, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, of Columbia University’s Teachers College, and Michael Lopez, of the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, of data from the Comprehensive Child Development Program revealed that families at two sites that successfully provided more home visits per participating family showed significant effects on child cognitive outcomes compared with control group families; families at sites that offered less home visiting were significantly below the control group in child outcomes. As noted in the Spring/Summer 1999 issue of The Future of Children, programs “rely to some extent upon changes in parental behavior to generate changes in children’s health and development. If parent involvement flags between visits, then changes in children’s behavior will be much harder to achieve” (Gomby et al., 1999). This general conclusion was repeated throughout the workshop by both practitioners and researchers.

Mildred Winter, of the Parents as Teachers National Center, Inc., cited one of the main barriers to the success of home visiting programs to be the lack of motivation of parents to commit to the program. Many others acknowledged that home visiting is a relatively invasive procedure that entails a huge commitment of time and energy on behalf of parents, primarily mothers. It is therefore not surprising that The Future of Children review indicated that families typically received only half the number of visits prescribed. “The consistency with which this occurs across the models suggests that this is a real phenomenon in implementation of home visiting programs” (Gomby et al., 1999). Even when motivated and eager to participate, as noted by workshop participants, families miss visits because of difficulties associated with rescheduling, given busy families and home visitors with large caseloads.

Workshop participants were in agreement that one of the keys to keeping the family engaged throughout the duration of the program is a good relationship between the home visitor and the family. In the Infant Health and Development Program, home visitors’ ratings of parental engagement in the visits were highly predictive of program effects. As noted by Janet Dean, of the Community Infant Program in Boulder, Colorado, “Home visitors need to create a good relationship -- a safe context -- with the family before they can help the family. ” Although some programs target children directly, most home visiting programs are premised on the belief that parents are effective mediators of change in their children, and therefore target the parents directly. Despite the positive findings of some evaluations (such as the reanalysis of data from the Comprehensive Child Development Program), Brooks-Gunn noted that, in general, there is

not much evidence to back up the belief in this premise, nor is there a good appreciation for the difficulty of creating sufficient behavioral change in parents to actually improve child functioning. Workshop participants were in agreement that what is needed is better measurement and understanding of the relationship between the home visitor and the mother.

Attrition is endemic to home visitation. Many families not only miss visits, but also leave the program altogether before it is scheduled to end. For example, of the programs reviewed in Spring/Summer 1999 issue of The Future of Children, attrition rates ranged from 20 to 67 percent. Anne Duggan, of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine, reported that the program ’s approach to retention can affect attrition rates. The three Hawaii Healthy Start programs that she studied had highly variable attrition rates (from 38 to 64 percent over one year). The program with the lowest attrition rate actively and repeatedly tracked down families that tried to drop out, whereas the program with the highest attrition rate assumed that if the parent did not want to be involved, it was not the program’s responsibility to push her.

What can programs do to increase engagement? Olds surmised that enrolling mothers into the Nurse Home Visiting Programs while they were still pregnant with their first child and therefore highly motivated to learn about effective parenting strategies improved retention rates. Another strategy, which was mentioned by many at the workshop, is to make parents part of the program planning process. This may help parents “buy into” the program from the beginning, in addition to ensuring that the program really addresses the needs of the families it intends to serve. Parents need to believe that the home visiting services will help them accomplish goals that they have set for themselves and that warrant an extensive commitment. Answering the question of how to improve engagement is still a big challenge and an issue that needs much more systematic examination as part of implementation studies.

Virtually every speaker at the workshop commented that the home visitor ’s role is critical. As noted by Melmed, “Any service program is only as good as the people who staff it.” In the case of home visiting, the demands on the staff are diverse and often stressful. They must have “the personal skills to establish rapport with families, the organizational skills to deliver the home visiting curriculum while still responding to family crises that may arise, the problem-solving skills to be able to address issues that families present in the moment when they are presented, and the cognitive skills to do the paperwork that is required” (Gomby et al., 1999). Workshop participants identified challenges associated with finding appropriate staff, retaining staff, offering the necessary training and supervision, and matching staff to families with differing needs and predilections, some of which are culturally based and others that are not.

Program designers differ in their views about appropriate staff. Some programs, such as the Nurse Home Visitation Program, rely heavily on professionals (people with degrees in fields relevant to home visiting, such as nursing), but the majority of home visiting programs use paraprofessionals who often come from the community being served and typically have less formal education or training than professional staff beyond that provided by the program. There is an active debate in home visiting over which type of staff is most effective at delivering the curriculum and achieving results. The Nurse Home Visitation Program is based on the premise

that nurses are more effective home visitors than paraprofessionals. An evaluation of the Nurse Home Visitation Program in Denver, Colorado, found that families visited by nurses have a lower rate of attrition and complete more visits than families visited by paraprofessionals, even though the paraprofessionals worked just as hard as the nurses to retain families. Olds speculated that the families conferred greater authority upon the nurses and that the nurses were better equipped to respond to the mothers’ needs and feelings of vulnerability. As a result, the mothers may have complied more willingly with the nurses ’ guidance.

Others see paraprofessionals as better than professionals at creating the essential relationship with the family, because there is less social distance between paraprofessionals and the families they serve. Pilar Baca, of the Kempe Prevention Research Center for Family and Child Health and a trainer of staff for the Nurse Home Visitation Program, noted that the choice of staff is really a question of “for whom, for what?” She argued for the development of “robust paraprofessional models” as an alternative to assuming that professionals will be the preferred or even feasible option for all circumstances.

Regardless of the prior background of the visitors, they invariably face extremely complex issues when working with families and require appropriate preparation, ongoing information, and constant feedback to perform their jobs well. Many at the workshop commented on the need for more extensive and higher-level staff training, both before the home visitor begins working with families as well as during the course of their employment. Two aspects of training were mentioned often at the workshop. The first pertained to ensuring that the home visitors are well versed and accepting of the desired objectives and the philosophy of the particular home visiting program that they are responsible for implementing. The second had to do with the relatively poor ability of some home visitors to recognize conditions such as maternal depression, substance abuse, and domestic violence that interfere with program implementation, family engagement, and effectiveness.

Staff turnover is a significant problem for many programs. For example, the Nurse Home Visitation Program in Memphis had a 50 percent turnover rate in nurses due to a nursing shortage in the community. Other programs relying more on paraprofessionals reported even higher turnover rates. The Nurse Home Visitation Program in Denver, for example, had no turnover among the nurses who were providing home visits, but substantial turnover among the paraprofessionals. The specific impact of turnover on the effectiveness of programs is unknown, but it is likely to present a real problem since the quality of the home visitor/mother relationship is so predictive of program efficacy.

In this area, home visiting may be able to learn from the experiences of the child care field, since both have similar levels of turnover. In the child care field, turnover has been linked to the low wages earned by child care workers as well as to the quality of care received by children and families. Home visiting positions are also typically low-paying and stressful, and it makes sense that many staff will leave if they find a better-paying opportunity. Other keys to staff retention discussed at the workshop include good supervision and good morale. Providing home-based services can be isolating for the home visitor and, as such, requires a higher, more intense level of supervision. At the same time, because supervisors do not typically accompany staff on home visits and therefore do not observe home visitors performing the intervention, it

can be difficult for them to help the home visitor reflect on and learn from their experiences. Despite these difficulties, home visitors need supervision that goes beyond “did you do your job or not” to include elements of social and emotional support, teamwork, and recognition of staff effort. Terry Carrilio, of the Policy Institute at the San Diego State University School of Social Work, aptly observed that the “process needs to reflect what you are trying to do. If a program does not treat its staffwell, how can we expect the staff to deliver a supportive service? ”

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

Cultural and linguistic considerations are also involved in the decision of who can best deliver home visiting services, but they encompass many other complex issues as well. Home visiting programs deal with fundamental beliefs about how a parent interacts with a child. These beliefs, which are heavily imbued with cultural meaning, provide the foundation for the design and implementation of any program. As noted by Baca, for example, it is likely to be more difficult for a home visitor from a culture different from that of the family to distinguish between practices and beliefs that are culturally different and those that are culturally dysfunctional. This applies as well to evaluators. Linda Espinosa, of the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Missouri, cautioned that there are possible ripple effects when “we start changing highly personal, highly culturally embedded ways of interacting and socializing children within the family unit. We hope the effects are positive, but we cannot ignore the possibility that they could be negative.” In this context, Espinosa specifically mentioned the potential for programs to upset “the fragile balance of power within the family.”

Decisions about using bicultural and bilingual home visitors are often determined by forces beyond the control of the program. For example, the Family Focus for School Success program in Redwood City, California, chose to hire paraprofessionals because, as Espinosa described, “there were no certificated or B.A.-level people who were bilingual and bicultural and who were floating around in the community waiting to be hired.” Program developers made the decision that having bilingual and bicultural staff was more important than having professional staff. This issue creates certain challenges when programs are expanded since it may not be possible to find enough people willing to be home visitors with the necessary qualifications. The basic question, as for all interventions, is: “Do our goals and outcomes align with the hopes, dreams, and aspirations of the families we serve?”

Domestic Violence, Maternal Depression, and Substance Abuse

Three conditions that can significantly impede the capacity of a home visiting program to benefit families were identified and discussed at the workshop: domestic violence, maternal depression, and substance abuse. Home visiting programs generally set goals that are preventive in nature: to prevent child abuse and neglect, to improve the nutrition and health practices of the mother, to reduce the number of babies born with low birthweight, and to promote school readiness and prevent school failure. However, the families that are targeted by home visiting programs often experience other problems, such as maternal depression, substance abuse, and domestic violence, that need to be addressed before the prevention goals of the program can be achieved.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Knock Knock, Teacher's Here: The Power Of Home Visits

Blake Farmer

Ninety percent of students at Hobgood Elementary in Murfreesboro, Tenn., come from low-income households. Most of the school's teachers don't. And that's a challenge, says principal Tammy Garrett.

"If you only know middle-class families, you may not understand at times why they don't have their homework or why they're tired," Garrett says.

When she became principal four years ago, Garrett decided to get her teachers out of their classrooms — and comfort zones — for an afternoon. Once a year, just before school starts, they board a pair of yellow buses and head for the neighborhoods and apartment complexes where Hobgood students live.

En route, the bus driver describes over the intercom how he picks up 50 children at one complex each morning. The teachers pump themselves up with a chant. After all, they're doing something most people don't enjoy: knocking on doors unannounced.

When the caravan arrives at a cluster of apartments, the teachers fan out and start knocking on doors of known Hobgood families. Some encounters don't get beyond awkward pleasantries and handing over fliers about first-of-the-year festivities. Others yield brief but substantive conversations with parents who might be strangers around school.

Jennifer Mathis has one child still at Hobgood and says she appreciates that the school came to her — since she has a hard time getting to school.

"I don't have a car. I can't drive because my back got broken in two places," she tells a trio of teachers standing in her doorway. "I'm a mom. I can't be there with all of them all the time."

Giving Home Visits A Try

There was a time when a teacher showing up on a student's doorstep meant something bad. But increasingly, home visits have become a tool to spark parental involvement. The National Education Association has encouraged more schools to try it out, and there's this national effort .

One district in Massachusetts just added money to pay teachers for the extra work involved. Traditional schools in Washington, D.C., tried out home visits after privately run charter schools used them to successfully engage parents.

In Murfreesboro, principal Garrett sees the brief visits as mutually beneficial. Parents get to meet their kids' teachers. And teachers get a clearer sense of the challenges many of their students struggle with on a daily basis.

"If a kid doesn't have a place to sleep or they have to share the couch with their siblings at night and there are nine kids with one bedroom or two bedrooms, it's important for them to see that — not to be sympathetic," she says. "It's to empower the teachers to change the lives of the kids."

It's serious business. But Danielle Hernandez, a special education teacher, says it's not the somber experience she'd feared. At one apartment complex, a dozen kids are out riding bikes on their last day of summer break.

"I know that these children, they go through a lot in their lives," Hernandez says. "But they get to have so much fun."

Teachers join in on that fun, borrowing kids' bikes for a cross-parking-lot drag race that generates howls from the adults.

Ashlee Barnes, a fourth-grade teacher at Hobgood, says she's a believer, even if home visits have yet to prove themselves as a difference-maker on standardized testing.

"We become more important in their lives than I think we can ever understand," she says. "I think the sooner you can start a relationship, you're going to see results on their performance in the classroom."

'It Makes Me Want To Cry'

The kids seem to genuinely enjoy the visits, even if they are a reminder that summer is over.

"I am so lucky," says fourth-grader Shelleah Stephens as she's introduced to Barnes, her new teacher. "All the teachers I have had have been so nice. It's great to see you."

Barnes hugs Shelleah, who is barefoot on the sidewalk in front of the unit where she lives with her father, Kenny Phillips. He's standing back, smiling as his daughter shows off her budding social skills.

"It just brings you this joy. It makes me want to cry," Phillips says.

Phillips runs a landscaping business and says long days have kept him from being as involved with his daughter's education as he'd like to be. Seeing this interaction has him a little choked up.

"It's just good to see her grow up and have people around her who care," he says. "Sometimes parents aren't there, man. Sometimes we gotta work. Sometimes we're gone a lot of the time. It's good to see [teachers] come out to the neighborhood like that. I know she's in good hands."

Phillips also grew up in Murfreesboro but says no teacher stopped by his house. He hopes to return the favor by making sure Shelleah finishes all her homework this year.

- Find It Fast

Funding Opportunities

- All Funding Opportunities

- What & Who We Fund

- PCORI's Research Funding Process

- What You Need to Know to Apply

- Merit Review

Applicant and Awardee Resources

Research & related projects.

- Explore Our Portfolio

- About Our Research

- On the Path to Impact

- PCORI in the Literature

- Peer Review

Engagement in Research

- Foundational Expectations for Partnerships

- Background on the Foundational Expectations

- Benefits of Engagement in Research

- Real-World Examples by Foundational Expectation

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Promotional Toolkit

- The Value of Engagement in Research

- Engagement Award Program

- Engagement Resources

- Engagement in Health Research Literature Explorer

- Influencing the Culture of Research

- Engage with Us

Implementation of Evidence

- Putting Evidence to Work

- Evidence Updates

- Evidence Synthesis Reports and Interactive Visualizations

- Emerging Topics: Reports and Horizon Scans

- PCORI Stories

Highlights of PCORI-Funded Research Results

Health topics.

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

- Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

- Rare Diseases

- Women's Health

- View All Topics

News & Events

- PCORI News Hub

- View All Events

- 2024 PCORI Annual Meeting

- The PCORI Strategic Plan

- Our Programs

- Our Vision & Mission

- Financial Statements and Reports

- Board of Governors

- Methodology Committee

- Authorizing Law

- Monitoring and Evaluating Progress

- Advisory Panel Openings

- Advisory Panels FAQs

- Application Review and Selection Process

- Procurement Opportunities

- Provide Input

- Value of Home Visits

Lessons Learned

- Balancing Flexibility and Fidelity in Pragmatic Trials

- Engaging Community Partners in Research Studies

- Engaging Patient Partners throughout the Research Process

- Assessing Resources Required to Deliver TC Interventions

- Using Research Findings to Make an Impact on Policy

- Optimizing Patient-Centered Outcomes Research: Insights from a Patient Partner

- Communicating Complex Research Findings

- The Value of Peer Mentors

- Engaging Multiple Stakeholders to Optimize Success

- Turning Service Delivery Challenges into Opportunities to Improve Care

Karen Miller, RN, is a care transition research nurse who coordinates operations for a PCORI-funded multi-site study, which examines whether patients with acute heart failure who receive patient-centered post-discharge care, including a home visit soon after ED discharge, close outpatient follow-up, and subsequent coaching calls, will avoid subsequent ED revisits and inpatient admissions.

Conducting home visits with patients recently discharged from the hospital or emergency department can be a valuable strategy to improve care transitions for patients. According to Karen Miller, RN, a research nurse who specializes in care transitions, home visits enable providers to get a better understanding of the patient within the broader context of their life, and help foster “an intimacy that you cannot achieve in the hospital—patients often share information during home visits that is not typically shared in the hospital setting.”

Miller is part of a research team studying whether patient-centered post-discharge care, including a home visit soon after discharge, can reduce ED revisits and admissions among patients with acute heart failure. A two-person team conducts a home visit and assesses the patient’s status, level of knowledge, and capability to manage their disease. According to Alan Storrow, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine and study co-investigator, the study team has learned that visiting patients in their home allows providers to “meet patients where they are” along the healthcare continuum and to tailor the patient’s care plan according to their individual needs, goals, and priorities.

In the home setting, patients are more likely to feel relaxed, comfortable, and have a sense of control, in contrast to ED and hospital environments, which can be intimidating. Miller notes that this sense of control translates to a greater sense of self-efficacy and engagement in their own care, an openness and receptivity to education about how to manage their disease, and a sense of true partnership with the provider. Home visits can also provide valuable support and education to family members and caregivers.

Miller says that delivering care in the home has changed her entire perspective on patient care. She also notes that feedback from patients has been extremely positive, with many patients commenting that participating in the program is “the most powerful experience they have had in health care."

Advice for Others

- Relationship building between patients and staff is key to the success of home visit interventions; begin forming a relationship before going to the patient’s home.

- Home visit interventions and care planning require clinical oversight; however, staff conducting home visits do not need to be clinicians.

- Emphasize a patient-centered approach and tailor the patient’s care plan based on their individual capabilities and goals; be flexible to each patient’s needs and priorities.

- Communicate with the patient’s primary care physician and other clinicians (e.g., cardiologist) at the outset and inform them about the patient’s involvement in the program. Emphasize that the visiting provider is a partner in the patient’s care and that the intervention complements and supports the patient’s primary care.

- Realize that interventions require concentrated support at the start of the education process, which can be reduced over time as patients learn to care for themselves.

What's Happening at PCORI?

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute sends weekly emails about opportunities to apply for funding, newly funded research studies and engagement projects, results of our funded research, webinars, and other new information posted on our site.

- Getting Around

- Senior Safety

- Assisted Living

- Care Professionals

- Home Health Care

- Transportation

- Senior Travel

- Resource Directory

7 Fun Ways to Celebrate a Pet-Friendly Family Reunion Out of…

Arthritis Becomes Leading Cause for Attendance Allowance Claims

Gum Health 101: Periodontal Disease in Older Adults

Preventing Falls in Seniors

Avoid Fighting Over Estate Issues

Saving With Senior Discounts

Helping a Parent Change to Assisted Living

10+ Benefits of the New 55+ Communities Now Available

6 Benefits of In-Home Hospice Care for Seniors in Orange County

Caregivers Get Worn Out, too!

How Does Caregiver Substance Abuse Happen?

Caregivers: Protecting Your Marriage

Fall Declutter and Organization

Additional Travel Tips for Seniors

Senior Citizen’s Day

10 Senior Travel Tips You Must Know

Advantages and disadvantages of home care & residential care.

As parents and loved ones become older, their wellbeing and safety can become major concerns . For all of us, our memories can struggle with age, and that can affect how well we look after ourselves. That can range from forgetting to take daily medicines , to having trouble getting out of bed, to falling in the night. It can be scary and upsetting for a grown up child to see their parent get old and struggle, but it is important to be aware when they need extra help. If you think that your parent needs some extra everyday assistance, there are many care options available. From home care workers to 24 hour residential care. Here we highlight some of the advantages and disadvantages of home care and residential care, to help you make the right decision for your loved ones.

For older adults that are able to do most of their day to day activities independently , but require additional support with cooking, cleaning, house work or getting out and about, home care can be a great option. Many organisations offer a range of support services, so that you and your parent can decide how much support to organise.

Advantages of using home care:

- Carers visit on a daily basis to assist with everything from bathing to cooking, cleaning, buying groceries and taking your parents to doctor’s appointments.

- Individuals can remain in living in their own home and maintain a degree of independence which can be really important for many.

- For those that prefer home comforts, residential care might be overwhelming so home care offers a great intermediary option.

- Home care ensures that family and friends can come over at any time and are not restricted by visitation hours which can be important in maintaining mental wellbeing and preventing loneliness .

- As the older person remains in their own home, and doesn’t get 24 hours care, often, home care is more affordable than residential care.

Disadvantages of home care:

- Although home care may be cheaper on the surface, the home may need fitting with ramps, railings and chairlifts, which can become costly and difficult to organize.

- Many home care agencies change from week to week and this can be unsettling for older people as well as their families. If home care is opted for, make sure all financial options are discussed and that everyone is happy to proceed.

- Some older people may not trust external support. This can make them feel vulnerable and alone. It is important to talk to older parents about their worries, and also consider whether the carer is right for them .

- For older people who are very social, some may enjoy the social side of sheltered housing or residential care- which is not offered by home care.

Residential Care

Residential care, strictly speaking, is out of home care for those with no longer able to live alone and who have low additional care needs. However, many people and organizations have come to use the term ‘residential care’ to describe all out of home care, including the most complex and intensive care such as nursing care and specialist care for those living with dementia .

If your parent needs extra support and is no longer able to live alone, then residential care can be the right solution. However, the confusion over what term to use can be just the tip of the iceberg with regards to deciding what type of out of home care to look for, and where to look for it. However, the most important thing is to start the research process, consider what advantages and disadvantages residential care could offer and discuss it with your parent . Here we have listed some of the most important pros and cons consider:

Advantages of residential care:

- Residential care is a safe and secure option for older people who are no longer able to live alone, or who are lonely. Residential care ensures all of the individuals living needs are taken care of and the home will provide a room and full board. This will remove the responsibility and worry about doing house work or making own meals.

- Personal and medical care is available 24/7, which can be really helpful for older adults who are lonely, prone to falling , or who require frequent medications but often forget. Having staff on hand all the time to help out can also reassure older people.

- Many residential care homes allow those who are married to stay together. This can be reassuring for many senior citizens who are afraid of separation.

- Most residential care facilities offer activities and trips. Activity programs provided by care teams can vary depending on location, and size of the home, however activities can include gardening, baking, gentle exercise and music. Some residential home also offer specialist activities such as brain training and complementary therapy.

Disadvantages of residential care:

- Residential care is typically more expensive that in home care due to its all inclusive nature and the fact that staff are available 24/7. This can make it difficult to access for some families.

- Residential care can be a nurturing environment. Organisations such as Oomph Wellness , can make life in the home active and enjoyable, offering engaging activities and help with getting out and about. However, despite the activities on offer, some older people can find it difficult to adapt to living in a care environment, and miss their independence. It is important that you talk to your loved ones about residential care, and ask them about the activities they would like to get involved with, and what worries them, before committing to a residential home.

- Although most homes have all-day visiting hours, the location of residential care can be some distance from the family. This makes it harder to maintain family bonds and regular activities. It is important that you consider distances when choosing which care home is right for your loved one.

After considering all the possible advantages and disadvantages, it’s important to remember that everyone is different, and that no matter how elderly your parent may be, or how much care they may require, it is important to include your parents in the discussion about their care to help them feel more comfortable and confident in the care that they receive.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Latest news.

5 Extraordinary Investments for Seniors

5 Tips For Surviving A Family Vacation

Home Staging Tips

Aging Alone: Are You Prepared?

Press Release – For Our Australian Audience: Industry Embraces Code Of Conduct For Retirement Living

How To Make The Most Of Your Newly Empty Nest

Follow us on instagram @seniorslifestylemagazine.

- Advertise With Us

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Affiliate Disclosure

- DCMA Notice

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 09 January 2013

Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review

- Shelley Peacock 1 ,

- Stephanie Konrad 2 ,

- Erin Watson 3 ,

- Darren Nickel 4 &

- Nazeem Muhajarine 2 , 5

BMC Public Health volume 13 , Article number: 17 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

248 Citations

39 Altmetric

Metrics details

The effectiveness of paraprofessional home-visitations on improving the circumstances of disadvantaged families is unclear. The purpose of this paper is to systematically review the effectiveness of paraprofessional home-visiting programs on developmental and health outcomes of young children from disadvantaged families.

A comprehensive search of electronic databases (e.g., CINAHL PLUS, Cochrane, EMBASE, MEDLINE) from 1990 through May 2012 was supplemented by reference lists to search for relevant studies. Through the use of reliable tools, studies were assessed in duplicate. English language studies of paraprofessional home-visiting programs assessing specific outcomes for children (0-6 years) from disadvantaged families were eligible for inclusion in the review. Data extraction included the characteristics of the participants, intervention, outcomes and quality of the studies.

Studies that scored 13 or greater out of a total of 15 on the validity tool ( n = 21) are the focus of this review. All studies are randomized controlled trials and most were conducted in the United States. Significant improvements to the development and health of young children as a result of a home-visiting program are noted for particular groups. These include: (a) prevention of child abuse in some cases, particularly when the intervention is initiated prenatally; (b) developmental benefits in relation to cognition and problem behaviours, and less consistently with language skills; and (c) reduced incidence of low birth weights and health problems in older children, and increased incidence of appropriate weight gain in early childhood. However, overall home-visiting programs are limited in improving the lives of socially high-risk children who live in disadvantaged families.

Conclusions

Home visitation by paraprofessionals is an intervention that holds promise for socially high-risk families with young children. Initiating the intervention prenatally and increasing the number of visits improves development and health outcomes for particular groups of children. Future studies should consider what dose of the intervention is most beneficial and address retention issues.

Peer Review reports

Caring for infants and young children can be challenging for many parents; it can be further complicated when families are poor, lack social support, or have addiction problems [ 1 ]. Home visiting (HV) programs attempt to address the needs of these at-risk families with young children by offering services and support that they might not otherwise access. Home visiting programs have been in existence now for more than 20 years [ 2 ]. The benefit of HV programs is that the service is brought to socially isolated or disadvantaged families in their own homes and as such, may increase their sense of control and comfort, allowing them to get the most benefit from services offered. Also offering the programs in the home environment allows home visitors to provide a more tailored approach to service delivery [ 2 , 3 ].

HV programs, however, have difficulties to overcome in order to deliver services. Target families may not accept enrolment into a program or when they do agree may later elect not to begin the program [ 3 ]. Some possible explanations for this include the facts that home visitors may be viewed as intruding or because families may find it difficult to open their homes to home visitors. Achieving consistency in program delivery can also be difficult; families may not receive the planned number of visits, and visitors may not deliver the content according to the program model [ 3 ]. Despite these challenges, the benefits of HV programs outweigh the limitations. To achieve the aims of HV programs it is important that they be shaped by the community and families they serve and that their outcomes be evaluated routinely as part of program improvement.

There are a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses that explore the effectiveness of HV programs with disadvantaged families [ 4 – 7 ], many of which focus on the prevention of child maltreatment [ 8 – 10 ]. We were not able to locate a systematic review that focused on the delivery of HV programs by paraprofessionals and the effect this method of service delivery has on children’s developmental and health outcomes, so we decided to conduct one to fill this gap in the literature. This work is important to policy-makers and program planners in that these types of programs may be desirable in regions where the higher costs associated with nurse-led HV interventions mean that they are not a feasible option.

The research question for this systematic review was: What is the effectiveness of paraprofessional HV programs in producing positive developmental and health outcomes in children from birth to six years of age living in socially high-risk families? For the purposes of this review, a paraprofessional is an individual delivering an HV program whose credentials do not include clinical training (e.g., developmental psychologist, etc.) and who is not licensed. Socially high-risk families are those who live in poor economic circumstances, receive government assistance or who have inadequate income to meet the needs of the family. We chose broad outcome measures to make the review wide-ranging. These definitions are reflective of the types of programs, families, and research being done with HV programs across North America and elsewhere.

Literature search strategies

An experienced health sciences librarian searched the CINAHL PLUS, Cochrane Library, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PSYCINFO and Sociological Abstracts databases. Weekly alerts from all databases except Cochrane Library were set up to allow inclusion of newly published articles. Where possible, results were limited to the English language with a publication date of 1990 or later (up to May 2012).

Assessment of studies using relevance and validity tools

The tools utilized for assessing the relevance and quality of the studies were based on previously developed tools [ 11 , 12 ]. Article titles and abstracts, when available, were screened by one reviewer to determine whether they might meet eligibility criteria: 1) publication date on or after 1990; 2) written in English; 3) involving an evaluation of an HV program delivered by paraprofessionals; 4) study population of mothers and/or children (0-6) from socially high-risk families; 5) including one of the following outcomes: birth, perinatal, developmental, health and/or risk for occurrences of child abuse/neglect; and 6) incorporation of a control group, pretest/post-test design or quasi-experimental design. A principal reviewer assessed all the papers, and one of two secondary reviewers independently evaluated their relevance, with a third to adjudicate if needed. When necessary, we contacted researchers to clarify components of their research.

Relevant articles were then evaluated to determine the research quality using a validity tool with five items with scores ranging from 0-3, for a total maximum quality score of 15. The tool assessed studies based on how well they addressed potential biases, through assessment of the: (a) design/allocation to intervention (e.g., random assignment {3}, matched cohort {1}); (b) attrition of complete sample (e.g., <17% {3}, >33% {0}); (c) control of confounders (e.g., controlled through RCT design {3}, no evidence of controlling {1}); (d) measurement tools (e.g., well-described/pre-tested tools and blinded data assessors {3}, lack of pretesting and blinding {1}); and (e) type and appropriateness of statistical analysis (e.g., multivariate analysis {3}, descriptive analysis {1}). Two reviewers independently assessed the quality and discussed articles to reach consensus when discrepancies occurred.

Data extraction

We performed data extraction on high-quality studies (i.e., those scoring 13 or greater out of a possible 15), using these categories: (a) study design; (b) purpose or problem; (c) sample details; (d) intervention frequency, duration and provider; (e) instrument(s)/measures utilized; and (f) results and implications of the study. This process was done independently by three reviewers, consulting with each other when necessary.

Data synthesis

We used descriptive synthesis to summarize the characteristics of the participants, intervention, outcomes, and quality of the included studies, based on data extracted. Due to the diversity of the outcomes included in the studies, varying types of statistical analysis conducted, and measures of associations reported, calculation of overall summary estimates (i.e., meta-analysis) was not possible. An alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the purposes of this review.

Results and discussion

Literature search.

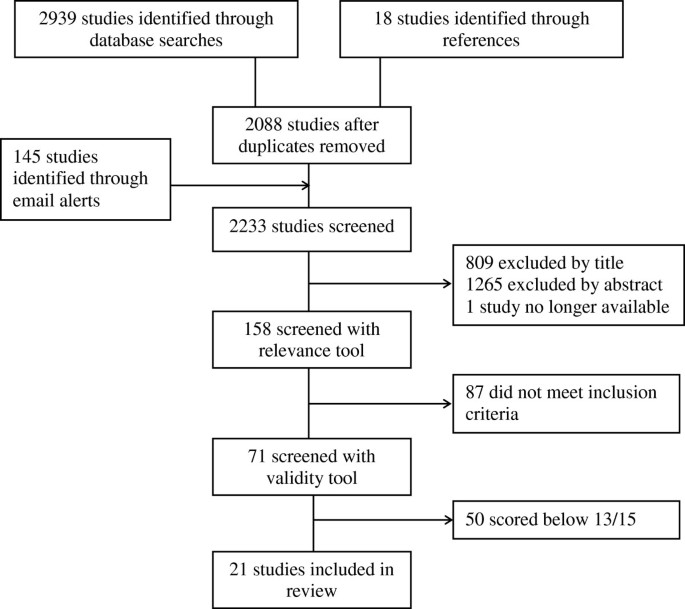

By using broad search criteria (in order to locate as many potential articles as possible) we identified 2939 records through database searches, which were reduced to 2088 records after duplicates were removed. We found an additional 18 articles by searching the reference lists of all potentially relevant studies. Email alerts resulted in a review of an additional 145 articles, resulting in a total of 2233 articles reviewed. Please see Table 1 that contains a sample of the initial search strategy employed.

Relevance and validity tool assessment

Of the 2233 studies, 809 were excluded by title alone, with an additional 1265 studies excluded following review of their abstracts. A second reviewer randomly selected 10 articles and independently performed the same screening process, reaching the same decisions on exclusion in all 10 cases. Screening and assessing abstracts of studies for relevance to the review yielded 159 potentially relevant articles. One study was no longer accessible, and therefore 158 were assessed with the relevance tool, yielding 71 relevant studies. Inter-rater reliability (kappa) ranged from 0.739 to 0.861 for the reviewing dyads. We applied the validity tool to these 71 studies, with an inter-rater reliability of 0.979, measured via the intra-class correlation. Studies with a score of 13 or higher out of a possible 15 ( n = 21) were deemed to be of high quality and included in the data extraction (see Figure 1 ).

Summary of selection process.

All studies retained in this review were randomized controlled trials with sample sizes ranging from 52-1297 participants; attrition was less than 24%, and most incorporated multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., analysis of co-variance, multiple regression analysis, or complier average causal effect). Four studies did not pilot test the measures, use well-described tools and/or blind data collectors. Most studies were conducted in the United States ( n = 15). The relevant outcomes measured were: (a) child abuse and neglect ( n = 6); (b) developmental delays ( n = 11); and (c) health assessment ( n = 10). For each outcome, we report whether the HV intervention had a demonstrable impact. Unless stated otherwise, all control group participants received the usual services offered in their community. Multiple relevant articles arose from the same projects, such as the Healthy Start Program (HSP) and Healthy Families Alaska/New York (see Table 2 for trial characteristics); for sake of clarity these articles are considered individually.

Child abuse and neglect

Child abuse and neglect was often measured using reports recorded with Child Protective Services (CPS) and/or self-reported behaviours of mothers. All of the studies focused on families deemed at-risk for child abuse. Please see Table 3 for a summary of the outcomes of the studies that assessed child abuse and neglect.

Barth [ 14 ] evaluated the Child-Parent Enrichment Project for its impact on preventing perinatal child abuse; pregnant women received, on average, 11 home visits over a 6 month period. In general, self-reported measures did not reveal significant differences in the prevention of child abuse between the intervention and control groups. Self-reported measures and lack of blinding of the assessors were seen as methodological weaknesses of this study.

Bugental and colleagues [ 16 ] assessed the effectiveness of two types of HV interventions compared to a control group. One intervention group received a program based on the Healthy Start model (called the unenhanced group) while the second group received HV with a cognitive change component (the enhanced group). Child abuse was measured on the basis of harsh parenting style using the self-report Conflict Tactics Scale. Bugental and colleagues [ 16 ] found that the enhanced intervention group had less frequent harsh parenting compared to the unenhanced or control groups ( p = 0.05). As well, the enhanced group mothers were significantly less likely to physically abuse ( p < 0.05) and least likely to spank/slap their children ( p < 0.05) compared to the unenhanced or control groups. These findings suggest that enhanced programming (i.e., HV with a cognitive change component) can effectively reduce the frequency and occurrence of harsh parenting among at-risk families. On the other hand, Barth [ 14 ] questions the efficacy of paraprofessional services in preventing abuse and neglect in high-risk families because participants in the Child-Parent Enrichment Program experienced no improvement in prevention of abuse.

Duggan, Berlin, Cassidy, Burrell, and Tandon [ 21 ] undertook an evaluation of Healthy Families Alaska (HFA), assessing reports on child abuse or maltreatment measured by the number of protective service reports filed. Levels of depression/anxiety and maternal attachment were considered moderators of the impact of HV intervention on child welfare. Among non-depressed mothers with moderate to high anxiety, HV was associated with decreased rates of substantiated child maltreatment ( p < 0.05). Among mothers who were not depressed, but had high discomfort with trust/dependence, HV was actually associated with increased rates of substantiated child maltreatment. Thus, benefits of this HV intervention seemed to be limited to certain subsets of at-risk mothers where a number of complex factors were at play. Studies by Duggan, Fuddy and colleagues [ 19 ] and Duggan, McFarlane and colleagues [ 20 ] of the HSP found that there is little impact from paraprofessional services in preventing child abuse and neglect in high-risk families. The researchers surmise that it may be that home visitors are inadequately trained to work with such complex high-risk families, as they were unable to identify family risks and did not provide professional referrals. All the above mentioned studies incorporated large sample sizes, blinded assessors, utilized multiple tools, and ensured study power to detect differences, which can lend credence to the findings.

DuMont and colleagues [ 22 ] assessed Healthy Families New York (HFNY) for the program’s effect on child abuse and neglect, as measured by review of CPS records and self-report of mothers over a two-year period. The researchers indicated that no program effects were noted for the sample as a whole, but that differences were detected between subgroups. By the second year of the intervention, the prevention sub-group (first-time mothers less than 19 years old admitted to the study at less than 30 weeks gestation) was less likely to report engaging in minor physical aggression (over the previous year; p = 0.02) and harsh parenting behaviours (within the previous week; p = 0.02) than was the control group. The “psychologically vulnerable subgroup” (women who were less likely to be first-time mothers, were older, and had a higher rate of prior substantiated CPS reports) were less likely to report acts of serious abuse or neglect compared to the control group at year two ( p < 0.05). The frequency of these acts was also significantly less than among the control group. DuMont and colleagues [ 22 ] suggest that intervening with specific groups of pregnant women can prevent child abuse before it has an opportunity to occur; however, unlike HFNY, assignment of intervention prenatally is not always considered in other large Healthy Families America HV programs.

Developmental delays

A total of 11 studies, one of which was a thesis, measured impacts related to developmental outcomes of children less than six years of age. Specific developmental outcomes included: (a) psychomotor and cognitive development; (b) child behaviour; and (c) language development. Please see Table 4 for the summary of outcomes for the 11 studies that assess developmental outcomes.

Psychomotor and cognitive development

Over half of the studies ( n = 6) utilized some version of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) to assess psychomotor and cognitive development. Black, Dubowitz, Hutcheson, Berenson-Howards, and Starr [ 15 ] undertook a study of an HV program that included weekly visits over a one-year period, conducting analysis on groups of children stratified by age (those < 12 months old and those 12-24 months old). After the 12-month study period, all of the children in the study showed a significant decline in cognitive development overall. However, younger children experienced significantly less decline ( p = 0.02) compared to age-matched control group children. Differences among the older children were not significant, suggesting that parents of infants may be more receptive to the benefits of an HV intervention compared to parents of toddlers, whose children are undergoing more complex developmental stages. It is important to note that this study may be limited in its generalizability due to the predominantly African American, single mother sample.

The HFAK program was evaluated over a two-year period by Caldera and colleagues [ 17 ] on developmental, behavioural and child health outcomes. The researchers found that 18 months after recruitment, children in the intervention group were significantly more likely to score within the normal range on the BSID (mental development index) than control children ( p < 0.05). The researchers cautioned that families with a low risk for child abuse may be the only to benefit from this program.

Grantham-McGregor, Powell, Walker and Himes [ 23 ] assessed effects of nutritional supplementation and psychosocial stimulation (conducted by home visitors) over a two year period with stunted 9 – 24 month old children in Jamaica. Only those findings relating to stimulation (alone and in combination) will be discussed here, as supplementation falls outside the scope of this review. Mothers and children assigned to the stimulation group participated in weekly play sessions led by the community health aides; these sessions were designed to promote the children’s development. The measures of development in this study were based on the Griffiths Mental Development Scales, including four subscales: locomotor, hand-eye coordination, hearing and speech, and performance. The researchers found statistically significant improvements in the first 12 months of the study for the stimulated group in regards to developmental quotient and the subscales of locomotor, hand-eye coordination and performance compared to the control group children (all p < 0.01).

Further, over the whole two years of the study [ 23 ] significant results continued for stimulated children with respect to developmental quotient and all the subscales ( p < 0.01). Multiple regression analyses of the final developmental quotient scores revealed that the group of children who received both supplementation and stimulation improved significantly more than the stimulated group ( p < 0.05). The findings suggest that small improvements in mental development can be seen in stunted children who receive a stimulation intervention alone, however, greater benefits are seen when nutritional supplementation is added to the HV intervention. This study does have two limitations: a small sample size, and the use of a developmental tool which was not standardized for use with the local population.

Hamadani, Huda, Khatun, and Grantham-McGregor [ 24 ] conducted a study of developmental outcomes of Bangladeshi children. They measured developmental assessment using the BSID (revised version) before and after 12 months of an HV intervention. Benefits of the intervention on motor development were not significant. They found intervention effects on the mental development index of the BSID ( p < 0.01), and further, the data were analyzed for children deemed undernourished compared to control group children. Children in the intervention group that were undernourished remained similar to the better-nourished children with respect to mental development on the BSID, but lagged behind on psychomotor development. This study, similar to Grantham-McGregor and colleagues [ 23 ], highlights the interacting or moderating effects of nutrition and its impact on overall child development.

Johnson, Howell and Molloy [ 25 ] assessed psychomotor and cognitive development using games with one-year-old children in Ireland; the intervention group received a home visit once a month. Mothers were asked how often they played either cognitive (e.g., hide and seek) or motor (e.g., playing with a ball) games with their child and this number was recorded with each game played receiving a score. The number of games was totaled with a higher score indicating children were assessed as more developmentally stimulated. Children in the intervention group were significantly more developmentally stimulated with cognitive games compared to the control group ( p < 0.01); motor development was not significantly different between groups. A note of caution with these findings is the fact that game playing was used as a means to assess developmental outcomes rather than using a standardized tool.

Nair, Schuler, Black, Kettinger and Harrington [ 31 ] compared the psychomotor and cognitive development of 18-month olds with a similar population of substance-abusing mothers. Using the BSID, children in the intervention group who received weekly visits for the first six months of life and then bi-weekly visits up to 24 months had significantly higher scores on the psychomotor developmental index at six months of age ( p = 0.041) and at 18 months ( p = 0.01) compared to the control group. The home visits were intended to enhance the mother’s communication with her infant. The researchers suggested there is benefit to using early intervention to improve high-risk children’s psychomotor and mental development.

Child behaviour

Caldera and colleagues [ 17 ] also assessed children for behavioural outcomes, finding that children in the HFAK program scored more favourably on the internalizing scale ( p < 0.01) and also on the externalizing scale ( p < 0.01) of the Child Behavior Checklist compared to control group children. The results from this study show that HFAK was able to reduce problem behaviours in young children, to a degree; other factors related to child behaviours (e.g., maternal depression or partner violence) were not influenced by the HFAK program.

Hamadani and colleagues [ 24 ] assessed child behaviour during testing using five 9-point scales. The researchers noted treatment effects for response to the examiner ( p = 0.01), cooperation with test procedures ( p = 0.005), emotional tone ( p = 0.03) and vocalizations ( p = 0.005); no treatment effect was noted for infant’s activity. This suggests that during testing children in the intervention group benefited in that they were more likely to be willing to engage with the examiner and were more vocal compared to the control group children. It is unclear what the usefulness of these five scales implies on aspects of child behaviour outside of the testing situation within the study.

Language development

Five studies considered findings with respect to language development. Black and colleagues [ 15 ] used the Receptive/Expressive Emergent Language Scale to assess differences in language development between the younger and older groups of children in their study. Both the younger and older children intervention groups experienced significantly less of a decline ( p = 0.05) in receptive and expressive language compared to their age-matched control groups.

The study by Necoechea [ 32 ] assessed language of three- to four-year-old children using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Expressive One-word Picture Vocabulary Test-revised, and the Developing Skills Checklist. Testing was done prior to initiation of the Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters program, and at the end of the 15-week intervention. Positive treatment effects were noted for the expressive language skills of children ( p < 0.01) in the intervention group, but no treatment effect was detected for receptive language skills or emergent literacy skills for those same children. The author noted that results should be viewed with caution, as there was substantial variation in the implementation of the intervention, such as number of visits and quality.

Health assessment

Measures assessed included (a) physical growth; (b) number of hospitalizations, illnesses, or injuries; and (c) up-to-date immunizations. Much of the data collected for these outcomes are from medical records. Ten of the included studies assessed health outcomes. Please see Table 5 for a summary of the health outcomes for each study.

Physical growth

Aracena and colleagues [ 13 ] assessed weight among the one year olds in their study and found no statistical difference between the intervention and control groups. The small sample size (n = 45 in each group) may account for part of this finding. Further, there are other factors to consider when assessing height and weight in young children that may not be amenable to a HV intervention (e.g., biological factors).

Black and colleagues [ 15 ] assessed both height and weight for the 12-month duration of their study. They found the HV intervention did not have an impact on children’s growth rates compared to the control group. Hamadani and colleagues [ 24 ] also found that the HV intervention they studied had no impact on improving weight or height for age, or weight for height. Unlike Black and colleagues, Hamadani and colleagues found all children experienced a deterioration in weight for height irrespective of which group they were in (nourished, undernourished, control or intervention). This may, in part, be indicative of the socioeconomic conditions in Bangladesh and the impacts such conditions have on quantities and sources of food.

The Lee and colleagues [ 28 ] study of the HFNY program is one of two studies with significant findings with respect to physical growth; they also included a measurement of low birth weight (i.e., < 2500 g). The earlier in pregnancy the intervention was initiated the lower the odds were of the mother having a low birth weight baby, indicating a dose–response relationship between HV and low birth weight. Compared to control group mothers, HFNY mothers who enrolled earlier than 30 weeks gestation (5.1% versus 9.8%; p = 0.022), at 24 weeks (5.1% versus 11.3%; p = 0.008), and at 16 weeks (3.6% versus 14.1%; p = 0.008) had significantly fewer low birth weight babies. Further analyses supported a dose–response, with greater benefit conveyed to those families enrolling earlier in pregnancy (i.e., thus receiving seven or more visits) (2.7% versus 7.2%; OR = 0.30; p = 0.079). In the Lee and colleagues study, African American women had the greatest reduction in numbers of low birth weight babies ( p = 0.022) suggesting that aspects of the environment that African American mothers may find themselves are amenable to change and can result in healthier pregnancies.

Le Roux and colleagues [ 29 ] evaluated an HV program that focused on improving the nutrition of children less than 5 years of age (average age 18 months). Over the one-year-period of the study, 43% of young children in the intervention group showed an acceptable weight-for-age and faster catch up growth compared to 31% in the control group ( p < 0.01). Appropriate weights at birth and weight gain into toddler years in children are important as this sets the stage for longer-term health benefits [ 29 ]. Findings of this study should be viewed with caution as there was potential for children in most need of supplementation to be steered toward the intervention group despite the intention to randomize participants.

Mclaughlin and colleagues’ [ 30 ] study was designed to assess if birth weight was improved when women were enrolled in an HV program prenatally that included a multi-disciplinary team with paraprofessional home visitors. When comparing the intervention group mothers to control group mothers, the researchers found no significant effect of the intervention in reducing the incidence of low birth weight babies. This finding is in contrast to Lee and colleagues’ findings with the HFNY program.

Number of hospitalizations, illnesses or injuries

Bugental and colleagues [ 16 ] investigated child health as an outcome of their enhanced HV program. As was mentioned previously, they assessed the effectiveness of two types of HV interventions (enhanced and unenhanced) compared to a control group. After completing a health interview with parents, a health score (i.e., frequency of illness, injuries, and feeding problems) was created for each child, where subscales were converted to z- scores and summed. Assessment completed at post-program revealed that the three groups were statistically different ( p = 0.02), with the enhanced HV group receiving the highest level of benefit in improving child health outcomes (i.e., having the fewest health problems).

In a study conducted in Ireland assessing HV impact on children’s hospitalization outcomes, Johnson and colleagues [ 25 ] found no significant differences between the intervention and control group. They did report however, that children from the intervention group had significantly longer in-hospital stays (14 days) compared to the control group children (7 days; p < 0.05); the researchers provide no explanation for such a peculiar finding. It would seem that this HV program failed to address aspects of various conditions that can lead to the hospitalization of children.

In a four-year follow-up study, Scheiwe, Hardy and Watt [ 33 ] report findings relevant to this review that are related to improvements in height and weight, general health, and number of dental caries after a seven-month HV intervention to improve feeding practices. Mothers from both the intervention and control groups reported whether their children had experienced any health problems within the last three months; children in the intervention group were less likely to have experienced any health problems compared to the control group children ( p = 0.01). All other health-related outcomes were statistically not significant between groups. The researchers caution that the significant findings are hard to explain and are likely only chance findings.

Up-to-date immunizations

One study assessed children’s immunization rates. Johnson and colleagues [ 25 ] found that significantly more one-year-old children in the intervention group received three of the primary immunizations (these were not listed in the study) compared to the control group ( p < 0.01). The results suggest that by empowering parents through an HV program, their children benefited both developmentally and by receiving timely immunizations.

In summary, significant improvements as a result of participating in an HV program are noted for particular parent–child groups. First, some children (e.g., those of psychologically vulnerable women) appear more likely to receive beneficial effects (i.e., protection from abuse and neglect) from an HV intervention, particularly when the intervention is initiated prenatally, than others. Second, HV is associated with developmental improvement and is particularly seen for cognition and problem behaviours, and somewhat less consistently for language skills. Third, in terms of health benefits, improvements are seen in birth weight and appropriate weight gain in early childhood (weight-for-age), fewer health problems, and timely immunizations in children. However, not all evaluated HV programs conclusively show beneficial effects on outcomes in socially high-risk children as evidenced by some studies included in this review.

Implications for practice and future research