What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

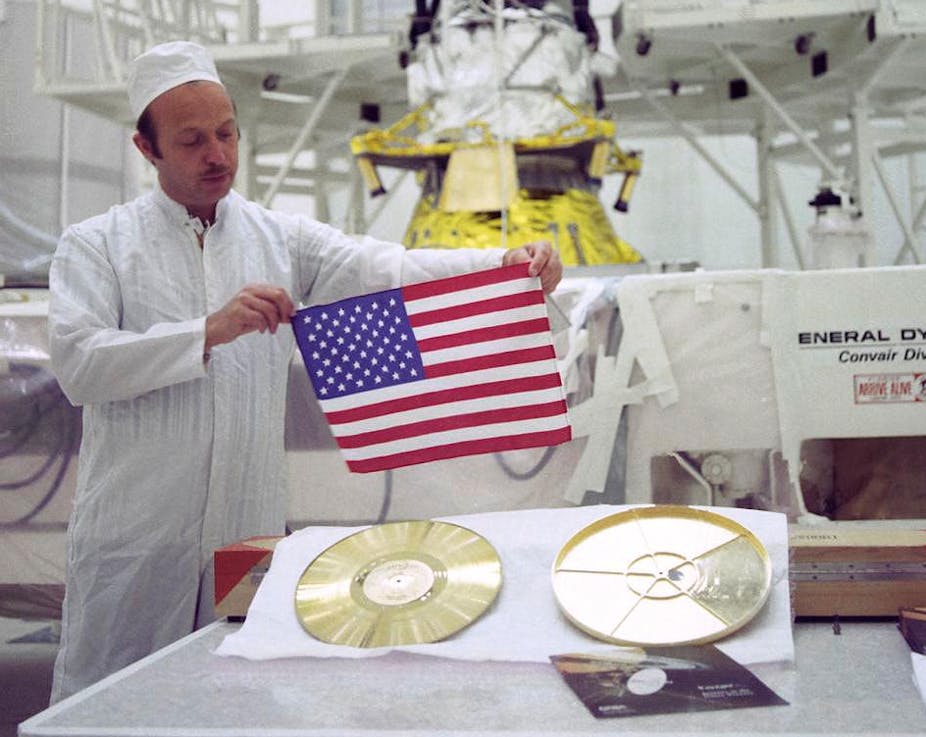

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

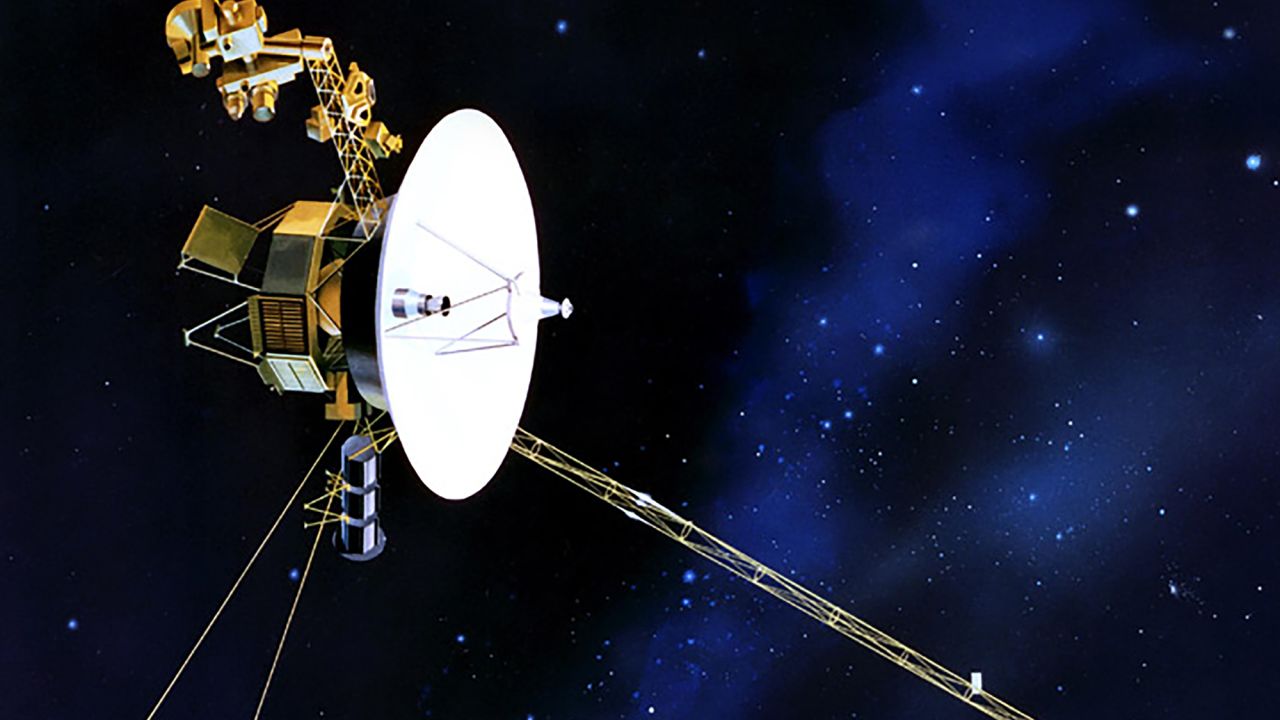

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Voyager Golden Record Was Made

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty . In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space. Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.

If you perched on Voyager 1 now—which would be possible, if uncomfortable; the spidery craft is about the size and mass of a subcompact car—you’d have no sense of motion. The brightest star in sight would be our sun, a glowing point of light below Orion’s foot, with Earth a dim blue dot lost in its glare. Remain patiently onboard for millions of years, and you’d notice that the positions of a few relatively nearby stars were slowly changing, but that would be about it. You’d find, in short, that you were not so much flying to the stars as swimming among them.

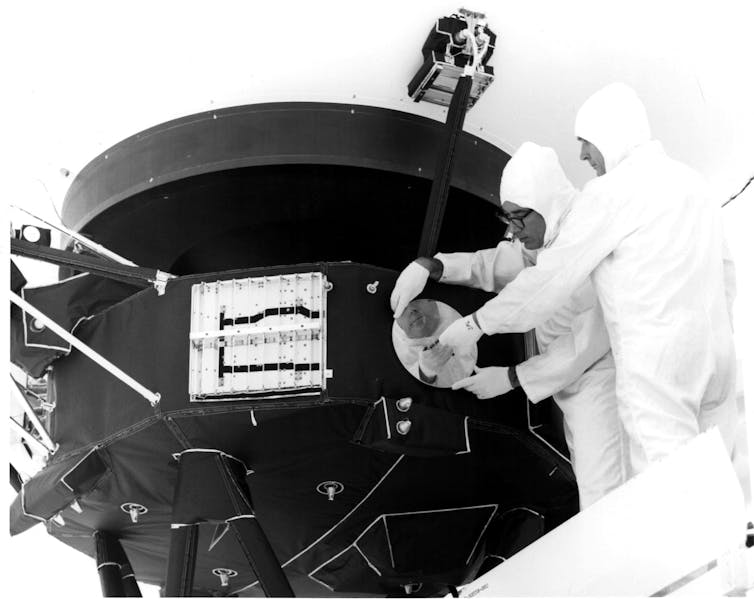

The Voyagers’ scientific mission will end when their plutonium-238 thermoelectric power generators fail, around the year 2030. After that, the two craft will drift endlessly among the stars of our galaxy—unless someone or something encounters them someday. With this prospect in mind, each was fitted with a copy of what has come to be called the Golden Record. Etched in copper, plated with gold, and sealed in aluminum cases, the records are expected to remain intelligible for more than a billion years, making them the longest-lasting objects ever crafted by human hands. We don’t know enough about extraterrestrial life, if it even exists, to state with any confidence whether the records will ever be found. They were a gift, proffered without hope of return.

I became friends with Carl Sagan, the astronomer who oversaw the creation of the Golden Record, in 1972. He’d sometimes stop by my place in New York, a high-ceilinged West Side apartment perched up amid Norway maples like a tree house, and we’d listen to records. Lots of great music was being released in those days, and there was something fascinating about LP technology itself. A diamond danced along the undulations of a groove, vibrating an attached crystal, which generated a flow of electricity that was amplified and sent to the speakers. At no point in this process was it possible to say with assurance just how much information the record contained or how accurately a given stereo had translated it. The open-endedness of the medium seemed akin to the process of scientific exploration: there was always more to learn.

In the winter of 1976, Carl was visiting with me and my fiancée at the time, Ann Druyan, and asked whether we’d help him create a plaque or something of the sort for Voyager. We immediately agreed. Soon, he and one of his colleagues at Cornell, Frank Drake, had decided on a record. By the time NASA approved the idea, we had less than six months to put it together, so we had to move fast. Ann began gathering material for a sonic description of Earth’s history. Linda Salzman Sagan, Carl’s wife at the time, went to work recording samples of human voices speaking in many different languages. The space artist Jon Lomberg rounded up photographs, a method having been found to encode them into the record’s grooves. I produced the record, which meant overseeing the technical side of things. We all worked on selecting the music.

I sought to recruit John Lennon, of the Beatles, for the project, but tax considerations obliged him to leave the country. Lennon did help us, though, in two ways. First, he recommended that we use his engineer, Jimmy Iovine, who brought energy and expertise to the studio. (Jimmy later became famous as a rock and hip-hop producer and record-company executive.) Second, Lennon’s trick of etching little messages into the blank spaces between the takeout grooves at the ends of his records inspired me to do the same on Voyager. I wrote a dedication: “To the makers of music—all worlds, all times.”

To our surprise, those nine words created a problem at NASA . An agency compliance officer, charged with making sure each of the probes’ sixty-five thousand parts were up to spec, reported that while everything else checked out—the records’ size, weight, composition, and magnetic properties—there was nothing in the blueprints about an inscription. The records were rejected, and NASA prepared to substitute blank discs in their place. Only after Carl appealed to the NASA administrator, arguing that the inscription would be the sole example of human handwriting aboard, did we get a waiver permitting the records to fly.

In those days, we had to obtain physical copies of every recording we hoped to listen to or include. This wasn’t such a challenge for, say, mainstream American music, but we aimed to cast a wide net, incorporating selections from places as disparate as Australia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, China, Congo, Japan, the Navajo Nation, Peru, and the Solomon Islands. Ann found an LP containing the Indian raga “Jaat Kahan Ho” in a carton under a card table in the back of an appliance store. At one point, the folklorist Alan Lomax pulled a Russian recording, said to be the sole copy of “Chakrulo” in North America, from a stack of lacquer demos and sailed it across the room to me like a Frisbee. We’d comb through all this music individually, then meet and go over our nominees in long discussions stretching into the night. It was exhausting, involving, utterly delightful work.

“Bhairavi: Jaat Kahan Ho,” by Kesarbai Kerkar

In selecting Western classical music, we sacrificed a measure of diversity to include three compositions by J. S. Bach and two by Ludwig van Beethoven. To understand why we did this, imagine that the record were being studied by extraterrestrials who lacked what we would call hearing, or whose hearing operated in a different frequency range than ours, or who hadn’t any musical tradition at all. Even they could learn from the music by applying mathematics, which really does seem to be the universal language that music is sometimes said to be. They’d look for symmetries—repetitions, inversions, mirror images, and other self-similarities—within or between compositions. We sought to facilitate the process by proffering Bach, whose works are full of symmetry, and Beethoven, who championed Bach’s music and borrowed from it.

I’m often asked whether we quarrelled over the selections. We didn’t, really; it was all quite civil. With a world full of music to choose from, there was little reason to protest if one wonderful track was replaced by another wonderful track. I recall championing Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark Was the Night,” which, if memory serves, everyone liked from the outset. Ann stumped for Chuck Berry’s “ Johnny B. Goode ,” a somewhat harder sell, in that Carl, at first listening, called it “awful.” But Carl soon came around on that one, going so far as to politely remind Lomax, who derided Berry’s music as “adolescent,” that Earth is home to many adolescents. Rumors to the contrary, we did not strive to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” only to be disappointed when we couldn’t clear the rights. It’s not the Beatles’ strongest work, and the witticism of the title, if charming in the short run, seemed unlikely to remain funny for a billion years.

“Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground,” by Blind Willie Johnson

Ann’s sequence of natural sounds was organized chronologically, as an audio history of our planet, and compressed logarithmically so that the human story wouldn’t be limited to a little beep at the end. We mixed it on a thirty-two-track analog tape recorder the size of a steamer trunk, a process so involved that Jimmy jokingly accused me of being “one of those guys who has to use every piece of equipment in the studio.” With computerized boards still in the offing, the sequence’s dozens of tracks had to be mixed manually. Four of us huddled over the board like battlefield surgeons, struggling to keep our arms from getting tangled as we rode the faders by hand and got it done on the fly.

The sequence begins with an audio realization of the “music of the spheres,” in which the constantly changing orbital velocities of Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, and Jupiter are translated into sound, using equations derived by the astronomer Johannes Kepler in the sixteenth century. We then hear the volcanoes, earthquakes, thunderstorms, and bubbling mud of the early Earth. Wind, rain, and surf announce the advent of oceans, followed by living creatures—crickets, frogs, birds, chimpanzees, wolves—and the footsteps, heartbeats, and laughter of early humans. Sounds of fire, speech, tools, and the calls of wild dogs mark important steps in our species’ advancement, and Morse code announces the dawn of modern communications. (The message being transmitted is Ad astra per aspera , “To the stars through hard work.”) A brief sequence on modes of transportation runs from ships to jet airplanes to the launch of a Saturn V rocket. The final sounds begin with a kiss, then a mother and child, then an EEG recording of (Ann’s) brainwaves, and, finally, a pulsar—a rapidly spinning neutron star giving off radio noise—in a tip of the hat to the pulsar map etched into the records’ protective cases.

“The Sounds of Earth”

Ann had obtained beautiful recordings of whale songs, made with trailing hydrophones by the biologist Roger Payne, which didn’t fit into our rather anthropocentric sounds sequence. We also had a collection of loquacious greetings from United Nations representatives, edited down and cross-faded to make them more listenable. Rather than pass up the whales, I mixed them in with the diplomats. I’ll leave it to the extraterrestrials to decide which species they prefer.

“United Nations Greetings/Whale Songs”

Those of us who were involved in making the Golden Record assumed that it would soon be commercially released, but that didn’t happen. Carl repeatedly tried to get labels interested in the project, only to run afoul of what he termed, in a letter to me dated September 6, 1990, “internecine warfare in the record industry.” As a result, nobody heard the thing properly for nearly four decades. (Much of what was heard, on Internet snippets and in a short-lived commercial CD release made in 1992 without my participation, came from a set of analog tape dubs that I’d distributed to our team as keepsakes.) Then, in 2016, a former student of mine, David Pescovitz, and one of his colleagues, Tim Daly, approached me about putting together a reissue. They secured funding on Kickstarter , raising more than a million dollars in less than a month, and by that December we were back in the studio, ready to press play on the master tape for the first time since 1977.

Pescovitz and Daly took the trouble to contact artists who were represented on the record and send them what amounted to letters of authenticity—something we never had time to accomplish with the original project. (We disbanded soon after I delivered the metal master to Los Angeles, making ours a proud example of a federal project that evaporated once its mission was accomplished.) They also identified and corrected errors and omissions in the information that was provided to us by recordists and record companies. Track 3, for instance, which was listed by Lomax as “Senegal Percussion,” turns out instead to have been recorded in Benin and titled “Cengunmé”; and Track 24, the Navajo night chant, now carries the performers’ names. Forty years after launch, the Golden Record is finally being made available here on Earth. Were Carl alive today—he died in 1996 at the age of sixty-two—I think he’d be delighted.

This essay was adapted from the liner notes for the new edition of the Voyager Golden Record, recently released as a vinyl boxed set by Ozma Records .

- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The search for life.

How life on Earth shapes the hunt for life out there.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

The Voyager Golden Record

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

August 14, 2017

Voyager Golden Records 40 Years Later: Real Audience Was Always Here on Earth

What message would you send to outer space?

By Jason Wright & The Conversation

NASA, JPL-Caltech

The following essay is reprinted with permission from The Conversation , an online publication covering the latest research.

Forty years ago, NASA launched Voyager I and II to explore the outer solar system. The twin spacecraft both visited Jupiter and Saturn; from there Voyager I explored the hazy moon Titan, while Voyager II became the first (and, to date, only) probe to explore Uranus and Neptune. Since they move too quickly and have too little propellant to stop themselves, both spacecraft are now on what NASA calls their Interstellar Mission , exploring the space between the stars as they head out into the galaxy.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Both craft carry Golden Records : 12-inch phonographic gold-plated copper records, along with needles and cartridges, all designed to last indefinitely in interstellar space. Inscribed on the records’ covers are instructions for their use and a sort of “map” designed to describe the Earth’s location in the galaxy in a way that extraterrestrials might understand.

The grooves of the records record both ordinary audio and 115 encoded images . A team led by astronomer Carl Sagan selected the contents, chosen to embody a message representative of all of humanity. They settled on elements such as audio greetings in 55 languages , the brain waves of “a young woman in love” (actually the project’s creative director Ann Druyan, days after falling in love with Carl Sagan ), a wide-ranging selection of musical excerpts from Blind Willie Johnson to honkyoku , technical drawings and images of people from around the world, including Saan Hunters, city traffic and a nursing mother and child.

Since we still have not detected any alien life, we cannot know to what degree the records would be properly interpreted. Researchers still debate what forms such messages should take . For instance, should they include a star map identifying Earth? Should we focus on ourselves, or all life on Earth? Should we present ourselves as we are, or as comics artist Jack Kirby would have had it, as “the exuberant, self-confident super visions with which we’ve clothed ourselves since time immemorial”?

But the records serve a broader purpose than spreading the word that we’re here on our blue marble. After all, given the vast distances between the stars, it’s not realistic to expect an answer to these messages within many human lifetimes. So why send them and does their content even matter? Referring to earlier, similar efforts with the Pioneer spacecraft , Carl Sagan wrote , “the greater significance of the Pioneer 10 plaque is not as a message to out there; it is as a message to back here.” The real audience of these kinds of messages is not ET, but humanity.

In this light, 40 years’ hindsight shows the experiment to be quite a success, as they continue to inspire research and reflection.

Only two years after the launch of these messages to the stars, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” imagined the success of similar efforts by (the fictional) Voyager VI. Since then, there have been Ph.D. theses written on the records’ content , investigations into the identity of the person heard laughing and successful crowdfunded efforts to reissue the records themselves for home playback.

The choice to include music has inspired introspection on the nature of music as a human endeavor, and what it would (or even could) mean to an alien species. If an ET even has ears, it’s still far from clear whether it would or could appreciate rhythm, tones, vocal inflection, verbal language or even art of any kind. As music scholars Nelson and Polansky put it , “By imagining an Other listening, we reflect back upon ourselves, and open our selves and cultures to new musics and understandings, other possibilities, different worlds.”

The records also represent humanity’s deliberate effort to put artifacts among the stars. Unlike everything on Earth, which is subject to erosion and all but inevitable destruction (from the sun’s eventual demise, if nothing else), the Golden Records are essentially eternal, a permanent time capsule of humanity. And unlike the Voyager spacecraft themselves – which were designed to have finite lifespans and whose journey into interstellar space was incidental to their primary function of exploring the outer planets – the Golden Records’ only purpose is to serve as ambassadors of humanity to the stars.

Placing artifacts in interstellar space thus makes the galaxy subject to the social studies, in addition to astronomy. The Golden Records mark our claim to interstellar space as part of our cultural landscape and heritage , and once the Voyager spacecraft themselves are not functional any longer, they will become proper achaeological objects . They are, in a sense, how we as a species have planted our flag of exploration in space. Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan muses , “Has NASA been to interstellar space because this spacecraft has? Have we, as a human species, [now] been to interstellar space?”

I would argue we have, and we are a better species for it. Like the Pioneer plaques and the Arecibo Message before them, the Golden Records inspire us to broaden our minds about what it means to be human; what we value as humans; and about our place and role in the cosmos by having us imagine what we might, or might not, have in common with any alien species our Voyagers eventually encounter on their very long journeys.

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article .

Voyager Golden Records 40 years later: Real audience was always here on Earth

Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Jason Wright acknowledges funding from NASA, the NSF, the Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Words at The Pennsylvania State University, and from Breakthrough Listen, part of the Breakthrough Initiatives sponsored by the Breakthrough Prize Foundation ( https://breakthroughinitiatives.org/ ).

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Forty years ago, NASA launched Voyager I and II to explore the outer solar system. The twin spacecraft both visited Jupiter and Saturn; from there Voyager I explored the hazy moon Titan, while Voyager II became the first (and, to date, only) probe to explore Uranus and Neptune. Since they move too quickly and have too little propellant to stop themselves, both spacecraft are now on what NASA calls their Interstellar Mission , exploring the space between the stars as they head out into the galaxy.

Both craft carry Golden Records : 12-inch phonographic gold-plated copper records, along with needles and cartridges, all designed to last indefinitely in interstellar space. Inscribed on the records’ covers are instructions for their use and a sort of “map” designed to describe the Earth’s location in the galaxy in a way that extraterrestrials might understand.

The grooves of the records record both ordinary audio and 115 encoded images . A team led by astronomer Carl Sagan selected the contents, chosen to embody a message representative of all of humanity. They settled on elements such as audio greetings in 55 languages , the brain waves of “a young woman in love” (actually the project’s creative director Ann Druyan, days after falling in love with Carl Sagan ), a wide-ranging selection of musical excerpts from Blind Willie Johnson to honkyoku , technical drawings and images of people from around the world, including Saan Hunters, city traffic and a nursing mother and child.

Since we still have not detected any alien life, we cannot know to what degree the records would be properly interpreted. Researchers still debate what forms such messages should take . For instance, should they include a star map identifying Earth? Should we focus on ourselves, or all life on Earth? Should we present ourselves as we are, or as comics artist Jack Kirby would have had it, as “the exuberant, self-confident super visions with which we’ve clothed ourselves since time immemorial”?

But the records serve a broader purpose than spreading the word that we’re here on our blue marble. After all, given the vast distances between the stars, it’s not realistic to expect an answer to these messages within many human lifetimes. So why send them and does their content even matter? Referring to earlier, similar efforts with the Pioneer spacecraft , Carl Sagan wrote , “the greater significance of the Pioneer 10 plaque is not as a message to out there; it is as a message to back here.” The real audience of these kinds of messages is not ET, but humanity.

In this light, 40 years’ hindsight shows the experiment to be quite a success, as they continue to inspire research and reflection.

Only two years after the launch of these messages to the stars, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” imagined the success of similar efforts by (the fictional) Voyager VI. Since then, there have been Ph.D. theses written on the records’ content , investigations into the identity of the person heard laughing and successful crowdfunded efforts to reissue the records themselves for home playback.

The choice to include music has inspired introspection on the nature of music as a human endeavor, and what it would (or even could) mean to an alien species. If an ET even has ears, it’s still far from clear whether it would or could appreciate rhythm, tones, vocal inflection, verbal language or even art of any kind. As music scholars Nelson and Polansky put it , “By imagining an Other listening, we reflect back upon ourselves, and open our selves and cultures to new musics and understandings, other possibilities, different worlds.”

The records also represent humanity’s deliberate effort to put artifacts among the stars. Unlike everything on Earth, which is subject to erosion and all but inevitable destruction (from the sun’s eventual demise, if nothing else), the Golden Records are essentially eternal, a permanent time capsule of humanity. And unlike the Voyager spacecraft themselves – which were designed to have finite lifespans and whose journey into interstellar space was incidental to their primary function of exploring the outer planets – the Golden Records’ only purpose is to serve as ambassadors of humanity to the stars.

Placing artifacts in interstellar space thus makes the galaxy subject to the social studies, in addition to astronomy. The Golden Records mark our claim to interstellar space as part of our cultural landscape and heritage , and once the Voyager spacecraft themselves are not functional any longer, they will become proper achaeological objects . They are, in a sense, how we as a species have planted our flag of exploration in space. Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan muses , “Has NASA been to interstellar space because this spacecraft has? Have we, as a human species, [now] been to interstellar space?”

I would argue we have, and we are a better species for it. Like the Pioneer plaques and the Arecibo Message before them, the Golden Records inspire us to broaden our minds about what it means to be human; what we value as humans; and about our place and role in the cosmos by having us imagine what we might, or might not, have in common with any alien species our Voyagers eventually encounter on their very long journeys.

- Extraterrestrial life

- Space exploration

- Golden Record

Research Fellow Community & Consumer Engaged Health Professions Education

Professor of Indigenous Cultural and Creative Industries (Identified)

Communications Director

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

The 116 photos NASA picked to explain our world to aliens

by Joss Fong

If any intelligent life in our galaxy intercepts the Voyager spacecraft, if they evolved the sense of vision, and if they can decode the instructions provided, these 116 images are all they will know about our species and our planet, which by then could be long gone:

When Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 launched into space in 1977, their mission was to explore the outer solar system, and over the following decade, they did so admirably.

With an 8-track tape memory system and onboard computers that are thousands of times weaker than the phone in your pocket, the two spacecraft sent back an immense amount of imagery and information about the four gas giants, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

But NASA knew that after the planetary tour was complete, the Voyagers would remain on a trajectory toward interstellar space, having gained enough velocity from Jupiter's gravity to eventually escape the grasp of the sun. Since they will orbit the Milky Way for the foreseeable future, the Voyagers should carry a message from their maker, NASA scientists decided.

The Voyager team tapped famous astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan to compose that message. Sagan's committee chose a copper phonograph LP as their medium, and over the course of six weeks they produced the "Golden Record": a collection of sounds and images that will probably outlast all human artifacts on Earth.

How would aliens know what to do with the Golden Record?

The records are mounted on the outside of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 and protected by an aluminum case. Etched on the cover of that case are symbols explaining how to decode the record. Put yourself in an extraterrestrial's shoes and try to guess what the etchings seek to communicate. Stumped? Hover over or click on the yellow circles for the intended meaning of these interstellar brain teasers:

What else is on the Golden Record?

Any aliens who come across the Golden Record are in for a treat. It contains:

- 116 images encoded in analog form depicting scientific knowledge, human anatomy, human endeavors, and the terrestrial environment. (These images appear in color in the video above, but on the record, all but 20 are black and white.)

- Spoken greetings in more than 50 languages.

- A compilation of sounds from Earth.

- Nearly 90 minutes of music from around the world. Notably missing are the Beatles, who reportedly wanted to contribute "Here Comes the Sun" but couldn't secure permission from their record company. For the video above, I chose to include "Dark Was the Night" by Blind Willie Johnson, a 1927 track Sagan described as "haunting and expressive of a kind of cosmic loneliness."

The committee also made space for a message from the president of the United States:

Where are they now?

Incredibly, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still communicating with Earth — they aren't expected to lose power until the 2020s. That's how NASA knew that Voyager 1 became the first ever spacecraft to enter interstellar space in 2012: The probe detected high-density plasma characteristic of the space beyond the heliosphere (the bubble of solar wind created by the sun).

Voyager 2 is currently traveling through the outer layers of the heliosphere. It's moving southward relative to Earth's orbit, while Voyager 1 is moving northward. In more than 40,000 years, they will each pass closer to another star than they are to our sun. (Or, more accurately, stars will pass by them).

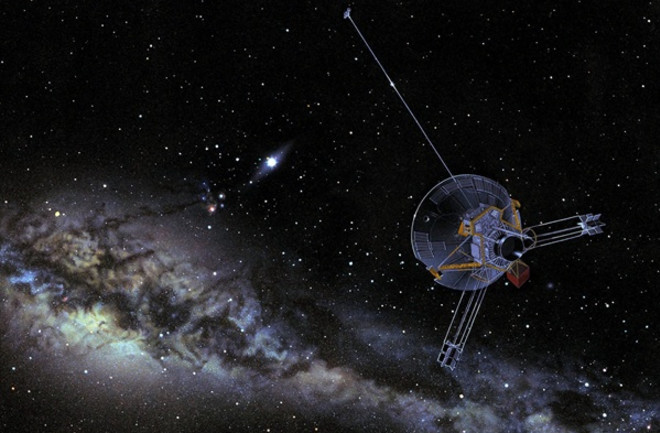

There are three other spacecraft headed toward interstellar space; two of them, Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11, are shown in this somewhat dated illustration:

NASA launched Pioneer 10 and 11 in 1972 and 1973, and has since lost communication with both. They aren't traveling as fast as the Voyagers, but they will eventually enter interstellar space as well.

They too, carry a message for extraterrestrial life, in the form of a 6-by-9-inch gold-anodized aluminum plaque, designed by Sagan and other members of the team that would go on to create the Voyager Golden Record five years later.

Like the Golden Record, the plaque features the pulsar map, uses hydrogen to define the binary units, and depicts humankind. NASA faced a backlash for the nudity of the human figures.

Another interstellar message

The fifth probe that will exit our solar system is New Horizons , the spacecraft that flew by Pluto in 2015. It is headed in a broadly similar direction as Voyager 2, but having launched in 2006, it's many years behind. It may not reach interstellar space for another 30 years.

New Horizons was sent into space without any message like the Golden Record, but it's not too late to add one. A group led by Jon Lomberg , a member of Sagan's Golden Record team, is trying to convince NASA to upload a crowdsourced message to the probe for any intelligent life that might come across it.

The spacecraft's memory system is similar to a flash drive, and it wouldn't be as durable as the copper records on Voyager. "The most conservative estimates are a lifetime of a few decades. Other physicists and engineers believe the message might remain for centuries or even millennia," says the website of the message initiative, adding, more hopefully, "Another unknown is the advanced technology possessed by any ETs who find the spacecraft. They might have ways of reading the faded memory we cannot yet imagine."

Most Popular

- What happened to Nate Silver

- A thousand pigs just burned alive in a barn fire

- Sign up for Vox’s daily newsletter

- What we know about the hundreds of pager explosions in Lebanon and Syria

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Video

Whether the US bans it everywhere could be up to the next president.

Why do so many people think pit bulls are violent?

Four reporters who have covered Kamala Harris at different points in her career narrate her rise from San Francisco prosecutor to presidential nominee.

The post-Covid pop-up boom, explained.

Why AI researchers think we’re close to getting interspecies chatbots.

Lawns aren’t natural, so why do so many Americans have one?

Advertisement

What Voyager's golden record tells ET about Earth

18 April 2009

Douglas Vakoch of the SETI Institute says any future messages sent to ET should reflect the human race as it really – warts and all . Click through this gallery to see what an alien civilisation might learn about earthlings from images on a golden record placed on each of the twin Voyager probes. Since launching in 1977, the spacecraft have travelled to the edge of the solar system.

Read more: “ Where am I? Voyager on the solar system’s frontier “

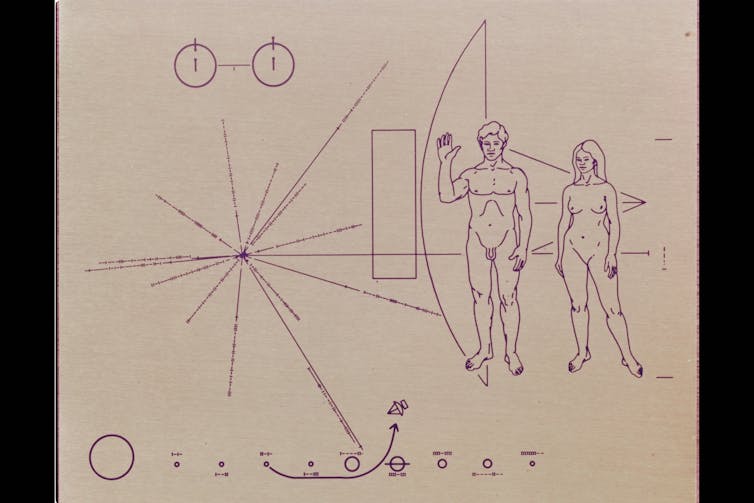

NASA’s Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecraft, which launched in 1972 and 1973, carried this design , which was etched on a 15×23-cm gold-anodised aluminium plate. The plaque was intended to inform any extraterrestrials who might come upon it when and where the spacecraft launched (using 14 pulsars as a reference point). “There’s also an image of a man and woman – perhaps the most cryptic for an extraterrestrial to understand,” says Vakoch. “The response NASA got [to that image] was quite surprising to them. Some were concerned that NASA was sending pornography into space.” (Illustration: NASA)

NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, which launched in 1977. Sounds and images intended to portray the diversity of life and cultures on Earth were encoded on a phonograph record made of gold-plated copper. A committee chaired by Carl Sagan assembled its contents: 115 images, a variety of natural sounds, music from different cultures and eras, and spoken greetings in 55 languages. Each record is encased in a protective aluminium jacket, together with a cartridge and a needle. Instructions, in symbolic language, explain the origin of the spacecraft and how to play the record. “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilisations in interstellar space,” said Sagan. “But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.” (Image: NASA)

“Like other messages that have been created for extraterrestrial audiences, the starting point of the Voyager recording was something we would expect extraterrestrials to have in common with us – and that’s basic math and science,” says Vakoch. (Illustration: Frank Drake)

This image defines basic units of mass, length and time. (Illustration: Frank Drake)

Included on the Voyager record are images of (clockwise from upper left) Mercury, Earth, Jupiter and Mars. (Image: NASA)

Overlaid on this satellite image of Egypt are some of the some of the most important gases in Earth’s atmosphere and their concentrations. The chemical formulas used here also appear in other Voyager slides, where there are diagrams of various atoms. (Illustration: NASA)

This illustration of DNA (top left) shows how “the chemistry of Earth is tied into our genetic material”, says Vakoch. Human reproduction is also the focus of multiple Voyager images, from the fertilisation of an egg by a sperm to a developing foetus to a silhouette of a man and a pregnant woman. “There’s an emphasis on reproduction in the Voyager recording, but also considerable caution in depicting nude human beings,” says Vakoch. “The image [of the man and woman] nicely portrays our ambivalence about sexuality.” (Illustrations: Jon Lomberg)

This image illustrates “licking, eating and drinking” (Image: National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center)

There are some Voyager images that relate to health and the human body, including this X-ray of a hand, says Vakoch – “but nothing that explicitly says, ‘Our bodies are frail.'” “The Voyager recordings intentionally minimise negative aspects of [human culture],” says Vakoch. “There was an intentional decision not to include a picture of a nuclear mushroom cloud [or] poverty and disease.” But long-lived alien civilisations are the ones most likely to be around to intercept our messages. “If they’re older, perhaps they’re also much more advanced than we are,” says Vakoch. “What would we have to say that would be of interest to them?” “I think the greatest thing we have to offer is to be honest about our current level of development, to highlight that we’re not sure that we’re even going to survive the next century . . . but that we have enough faith that we will continue to exist that we are making an effort to reach out to other civilisations.” (Image: National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center)

This illustration of vertebrate evolution shows representatives of the major vertebrate groupings, including amphibians, birds and mammals. The image of the man and woman at top right is quite similar to the drawing that was on the Pioneer plaque , with one difference – in the Pioneer image of the early 1970s, the man is raising a hand in greeting, but in this image from a few years later, the woman is waving hello. “Just in the span of a few short years, we saw a responsiveness in NASA to [include] a more adequate representation of women by showing a woman not as passively standing next to a man but as being a member of a couple that was actively sending greetings to other worlds,” says Vakoch. (Illustration: Jon Lomberg)

NASA really made an effort with Voyager to include images and sounds from around the world. “What’s unique about the Voyager recording is there’s really an emphasis on describing the breadth of human experience,” says Vakoch. “Really it’s the best portrayal of human diversity of any messages that have been sent out in space.” Still, the diversity it displays is limited – there are no images representing homosexuality, for example. “I think any interstellar message is in part a reflection of its times,” he says. “It may well be that if NASA sends out another image in the future, it may include a picture of two men or two women holding hands.” (Images: United Nations)

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Air jacket helps 'scuba-diving' lizards stay underwater for longer

Environment

People hugely underestimate the carbon footprints of the 1 per cent.

Subscriber-only

Quantum computers teleport and store energy harvested from empty space

Our reality seems to be compatible with a quantum multiverse

Popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

Golden Record Sounds and Music

Sounds of earth.

The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft.

Music from Earth

The following music was included on the Voyager record.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

CNN values your feedback

One of the most iconic pieces of space exploration history goes up for auction

Editor’s Note: Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

One of the most iconic pieces of space exploration history is up for auction.

When NASA’s twin Voyager probes lifted off to explore the solar system just weeks apart in 1977, they carried identical golden records designed as the first recorded interstellar message from humankind to potential intelligent life in the cosmos.

The records had both audio and visuals that aimed to capture Earth’s diversity of life and culture, including greetings in 59 human languages and 115 images of life.

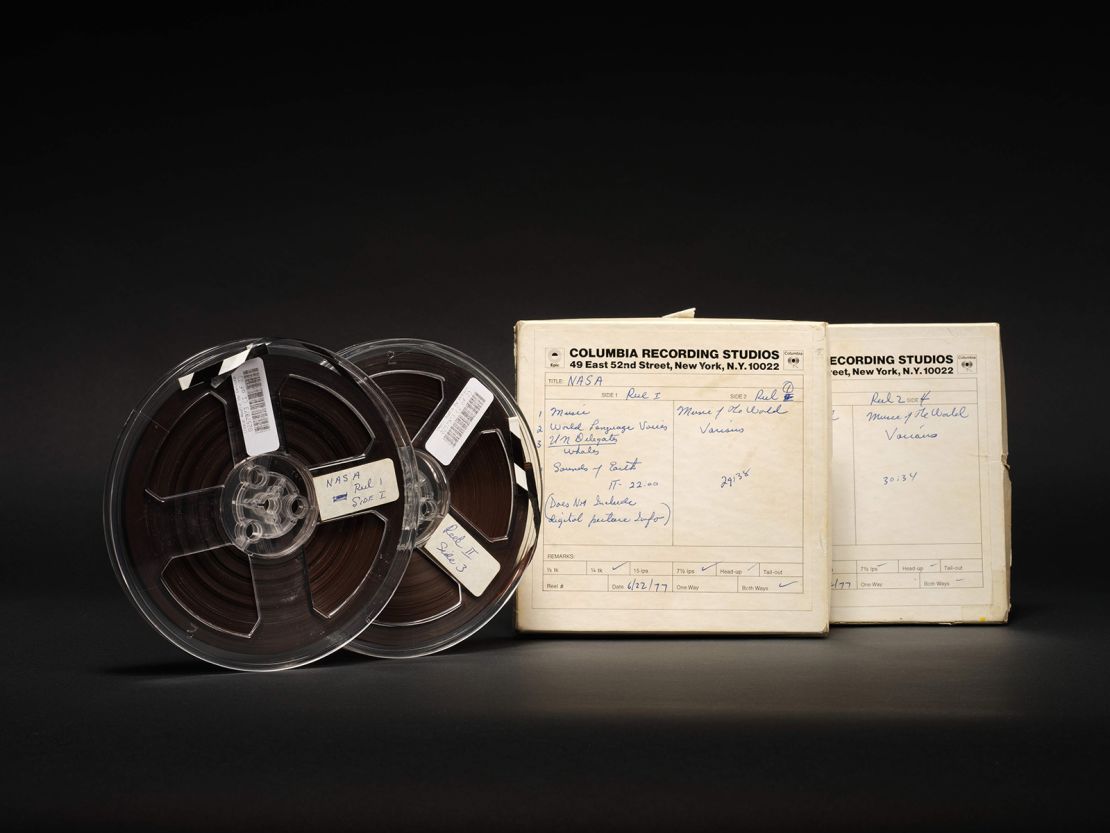

Now, a copy of the master recording for NASA’s Voyager Golden Record — the one kept by the late astronomer Carl Sagan and his wife, producer Ann Druyan — will be for sale at Sotheby’s New York on Thursday.

The recordings, contained on two double-sided reels of audiotape, are expected to fetch between $400,000 and $600,000. The audio quality of both tapes is “excellent,” according to the auction house.

The tapes are still in their original Columbia Recording Studios boxes, marked by handwritten labels. One reel includes music, humpback whale songs, United Nations delegates speaking, greetings and other sounds from across the world. The second tape features different styles of world music, including Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” Senegalese percussion, a Peruvian wedding song, a Navajo night chant and an Indian vocal raga, according to Sotheby’s.

Sagan and Frank Drake, both professors of astronomy at Cornell University at the time, were approached by officials at NASA to create the unique record as a follow-up to their work on the plaque aboard Pioneer 10 . Fellow Pioneer collaborator Linda Salzman also joined the committee, along with Druyan as creative director. The team had six months to capture the sounds and visuals of Earth.

Druyan compiled a sound essay of the history of Earth, weaving into it recordings of a rain forest humming with life, the brain waves and heart sounds of a young woman in love, and a mother’s first words to her baby. Additionally, the record included sounds that provided context for the celestial neighborhood around our planet, such as a distant pulsar and a rapidly rotating neutron star.

Eight copies of the record, made of copper and plated in gold, were produced, including the two that flew to space. Each record cover was etched with symbols depicting how to locate the sun and instructions on how to play the record.

The records, now traveling beyond our solar system through interstellar space, were designed to last between 1 billion and 5 billion years. A hand-carved inscription on the records reads, “To the makers of music — all worlds, all times,” serving as the only example of human handwriting on each Voyager mission.

An unexpected journey

When the Voyager probes launched in 1977, no one expected that the twin spacecraft would have their missions extended from four years to 45 years and counting.

Now, the mission team is getting creative with its strategies for the power supply and instruments on both Voyager 1 and 2 to enable both probes to continue collecting valuable data as they explore uncharted interstellar territory.

Voyager 1 is currently the farthest spacecraft from Earth at about 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) away, while Voyager 2 has traveled more than 12 billion miles (20 billion kilometers) from Earth, said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Both are in interstellar space and the only spacecraft to operate beyond the heliosphere, the sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends well beyond the orbit of Pluto.

As the sole extensions of humanity outside the heliosphere’s protective bubble, the two probes are alone on their cosmic treks as they travel in different directions.

Think of the planets of the solar system as existing in one plane. Voyager 1’s trajectory took it up and out of the plane of the planets after it passed Saturn, while Voyager 2 passed over the top of Neptune and moved down and out of the plane of planets, Dodd said.

The information collected by these long-lived probes is helping scientists learn about the cometlike shape of the heliosphere and how it protects Earth from energized particles and radiation in interstellar space.

But it has taken a lot of care and monitoring to keep the “senior citizens” operating, Dodd said.

“I kind of describe them as twin sisters,” Dodd previously told CNN . “One has lost its hearing and it needs some hearing aids, and another one has lost some sense of touch. So, they’ve failed differently over time. But in a general sense, they’re very healthy for how old they are.”

As long as both Voyager 1 and 2 remain healthy, it’s likely the aging probes will continue their record-breaking missions for years to come.

Show all

'.concat(e,"

'.concat(i,"

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

Will Aliens Understand Voyager's Golden Record?

Could an alien observer truly understand the messages we have sent to the stars.

The Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft famously contain messages to anyone who might someday find them. Both Pioneers carry a plaque, while the Voyagers carry a phonograph record. An enormous amount of effort went into creating these objects, but could an alien observer truly understand the messages we have sent to the stars?

While we cannot take anything for granted when it comes to how these messages might or might not be interpreted, let’s assume that the beings who might find the spacecraft can at least see or hear with eyes or ears similar to our own. Each message was designed with not only the information it was to carry in mind, but also the means to establish understanding through common denominators found throughout the universe.

The Pioneer Plaque

Pioneer 10 and 11 each carry a 6 x 9-inch (15 x 23 centimeters), gold-anodized aluminum plaque. The plaque is affixed to support struts close to the spacecraft’s bus (main body). Carl Sagan and Frank Drake played key roles in designing the plaque and Linda Salzman Sagan, Sagan’s wife at the time, was the artist who actually drew the images engraved on the plaque.

The most striking feature of the plaque are the figures of the man and the woman overlying the silhouette of the Pioneer spacecraft itself. While this does clearly convey our physical size and shape, as well as that sexual dimorphism is present in humans, the facial features of the couple have little detail and the sort of sensory organs are being depicted (the couple’s ears are barely shown at all) might be unclear. The man and woman both have their mouths closed, and viewers might not understand that these are even mouths at all. Given how the image is drawn, an observer could also be forgiven for not understanding that both the male and female have hair on their heads.

The couple both have a bland expression (which may have been an attempt to avoid anything that could be interpreted as hostile) and the man is seen raising his right hand with the palm facing the viewer. While this gesture clearly conveys a greeting when viewed by another human, an extraterrestrial may have no way of interpreting this gesture. (Could you interpret a gesture made by an antelope … or a praying mantis?) It does show, however, that humans have opposable thumbs, as well as the general range of motion of the upper limbs.

With regards to the scientific data presented, the top left of the plaque shows the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen as a means of conveying to the reader baseline units of time (0.7 nanoseconds, the frequency of the transition) and distance (21 cm, the wavelength of the light released by the transition). If one is able to deduce that the image is that of hydrogen, the time and distance should be understandable.

The plaque also contains a map of our sun relative to 14 pulsars as well as the center of our galaxy, conveying both the distances to the pulsars and their frequency in binary notation. As this image conveys copious objective data, a spacefaring species might well be able to easily interpret it.

Finally, the plaque contains a map of the solar system. The solar system map is likely among the more easily interpreted parts of the plaque, with Pioneer shown to have originated from the third planet. The plaque was created at a time when Pluto was still considered the ninth planet (before the discovery of other trans-Neptunian dwarf planets such as Eris and Sedna, among others), but it would still direct the reader’s attention to Earth if they were able to figure out that our solar system was the one depicted.

Voyager’s Golden Record

The Voyager record asks more of whoever finds it but gives more information in return. These phonographs, attached to the spacecraft bus, feature a cover illustration and over 90 minutes of audio on the reverse side. The cover illustration features the same image of hydrogen and the same pulsar map as found on the Pioneer plaque. Of critical importance, the Voyager records convey instructions on how to play them, such as how to affix the attached stylus, at what rate of rotation the record must be spun, and the proper waveform of signals generated by the record. It also explicitly tells the reader how to know if they are viewing the images properly via an engraving of what the first image (a circle) should look like. While this may seem very daunting, the challenge is primarily technical and might well be easily overcome by an advanced spacefaring species.

An alien species might well find more difficulty in interpreting the audio samples, music, and images contained on the record. There are over 50 greeting messages in different languages. While the specifics of the messages are likely to be uninterpretable, they would at least convey to the listener the diversity of the creatures who created the Voyagers.

Similarly, the musical selections chosen demonstrate a wide range of human musical styles (ranging from works of Beethoven and Stravinsky to those of Chuck Berry, among others). While the lyrics of “Johnny B. Goode” are probably gibberish to an extraterrestrial, the beat and rhythm of the song would convey a tremendous amount to an alien listener.

Of perhaps the greatest importance are the 115 images encoded on the record. The first six images, if decoded properly, provide immense technical data for the reader regarding mathematical definitions, scales and sizes, as well as additional information regarding our location and how to find us. Images of the sun and its spectrum, as well as some of the planets in our solar system, could help the discoverer of the Voyagers to find us should they decide to pay the Earth a visit. There are also approximately 20 medical and scientific diagrams including the structure of DNA and detailed images of human anatomy. These images could likely be interpreted correctly given their concrete nature.

The Voyager record also contains a plethora of images of humans engaged in a variety of activities (including eating, looking through a microscope, and even going on a spacewalk). While many of these images would be hard to interpret (e.g., a picture of a woman licking an ice cream cone or a photo of a string quartet) the images would at least convey that humans have created a complex civilization with some degree of advanced technology.

The Big Picture

As Marshall McLuhan famously said, “The medium is the message.” While the recipients of the Pioneer plaque or the Voyager record might never understand everything we are trying to convey, the fact that these messages were placed on interstellar spacecraft carry (both for them and for us) a deeper message — that humans created these spacecraft and that we want to tell the universe who we are.

- extraterrestrial life

- space exploration

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Voyager Golden Record, Cover of the Voyager Golden Record, The golden record's location on Voyager (middle-bottom-left).

Item preview.

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

The Golden Record

Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule, intended to communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials. The Voyager message is carried by a phonograph record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

The Golden Record Cover

In the upper left-hand corner is an easily recognized drawing of the phonograph record and the stylus carried with it. The stylus is in the correct position to play the record from the beginning. Written around it in binary arithmetic is the correct time of one rotation of the record, 3.6 seconds, expressed in time units of 0,70 billionths of a second, the time period associated with a fundamental transition of the hydrogen atom. The drawing indicates that the record should be played from the outside in. Below this drawing is a side view of the record and stylus, with a binary number giving the time to play one side of the record - about an hour.

The information in the upper right-hand portion of the cover is designed to show how pictures are to be constructed from the recorded signals. The top drawing shows the typical signal that occurs at the start of a picture. The picture is made from this signal, which traces the picture as a series of vertical lines, similar to ordinary television (in which the picture is a series of horizontal lines). Picture lines 1, 2 and 3 are noted in binary numbers, and the duration of one of the "picture lines," about 8 milliseconds, is noted. The drawing immediately below shows how these lines are to be drawn vertically, with staggered "interlace" to give the correct picture rendition. Immediately below this is a drawing of an entire picture raster, showing that there are 512 vertical lines in a complete picture. Immediately below this is a replica of the first picture on the record to permit the recipients to verify that they are decoding the signals correctly. A circle was used in this picture to ensure that the recipients use the correct ratio of horizontal to vertical height in picture reconstruction.

The drawing in the lower left-hand corner of the cover is the pulsar map previously sent as part of the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11. It shows the location of the solar system with respect to 14 pulsars, whose precise periods are given. The drawing containing two circles in the lower right-hand corner is a drawing of the hydrogen atom in its two lowest states, with a connecting line and digit 1 to indicate that the time interval associated with the transition from one state to the other is to be used as the fundamental time scale, both for the time given on the cover and in the decoded pictures.

Electroplated onto the record's cover is an ultra-pure source of uranium-238 with a radioactivity of about 0.00026 microcuries. The steady decay of the uranium source into its daughter isotopes makes it a kind of radioactive clock. Half of the uranium-238 will decay in 4.51 billion years. Thus, by examining this two-centimeter diameter area on the record plate and measuring the amount of daughter elements to the remaining uranium-238, an extraterrestrial recipient of the Voyager spacecraft could calculate the time elapsed since a spot of uranium was placed aboard the spacecraft. This should be a check on the epoch of launch, which is also described by the pulsar map on the record cover.

The Voyager Golden Records are two phonograph records that were included aboard both Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended for any intelligent extraterrestrial life form who may find them. The records are a sort of time capsule .

Although neither Voyager spacecraft is heading toward any particular star, Voyager 1 will pass within 1.6 light-years ' distance of the star Gliese 445 , currently in the constellation Camelopardalis , in about 40,000 years .

Carl Sagan noted that "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced space-faring civilizations in interstellar space, but the launching of this 'bottle' into the cosmic 'ocean' says something very hopeful about life on this planet."

The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University . The selection of content for the record took almost a year. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by surf, wind, thunder and animals (including the songs of birds and whales ). To this they added musical selections from different cultures and eras, spoken greetings in 55 ancient and modern languages, other human sounds, like footsteps and laughter (Sagan's), and printed messages from U.S. president Jimmy Carter and U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim . The record also includes the inspirational message Per aspera ad astra in Morse code .

The collection of images includes many photographs and diagrams both in black and white, and color. The first images are of scientific interest, showing mathematical and physical quantities, the Solar System and its planets, DNA , and human anatomy and reproduction . Care was taken to include not only pictures of humanity, but also some of animals, insects, plants and landscapes. Images of humanity depict a broad range of cultures. These images show food, architecture, and humans in portraits as well as going about their day-to-day lives. Many pictures are annotated with one or more indications of scales of time, size, or mass. Some images contain indications of chemical composition . All measures used on the pictures are defined in the first few images using physical references that are likely to be consistent anywhere in the universe .

The musical selection is also varied, featuring works by composers such as J.S. Bach (interpreted by Glenn Gould ), Mozart , Beethoven (played by the Budapest String Quartet ), and Stravinsky . The disc also includes music by Guan Pinghu , Blind Willie Johnson , Chuck Berry , Kesarbai Kerkar , Valya Balkanska , and electronic composer Laurie Spiegel , as well as Azerbaijani folk music ( Mugham ) by oboe player Kamil Jalilov . The inclusion of Berry's " Johnny B. Goode " was controversial, with some claiming that rock music was "adolescent", to which Sagan replied, "There are a lot of adolescents on the planet." The selection of music for the record was completed by a team composed of Carl Sagan as project director, Linda Salzman Sagan , Frank Drake , Alan Lomax , Ann Druyan as creative director, artist Jon Lomberg , Timothy Ferris as producer, and Jimmy Iovine as sound engineer.

The Golden Record also carries an hour-long recording of the brainwaves of Ann Druyan . During the recording of the brainwaves, Druyan thought of many topics, including Earth's history, civilizations and the problems they face, and what it was like to fall in love.

After NASA had received criticism over the nudity on the Pioneer plaque (line drawings of a naked man and woman), the agency chose not to allow Sagan and his colleagues to include a photograph of a nude man and woman on the record. Instead, only a silhouette of the couple was included. However, the record does contain "Diagram of vertebrate evolution", by Jon Lomberg , with drawings of an anatomically correct naked male and naked female, showing external organs.

The pulsar map and hydrogen molecule diagram are shared in common with the Pioneer plaque .

The 115 images are encoded in analogue form and composed of 512 vertical lines. The remainder of the record is audio, designed to be played at 16⅔ revolutions per minute.

Jimmy Iovine , who was still early in his career as a music producer, served as sound engineer for the project at the recommendation of John Lennon , who was contacted to contribute but was unable to take part.

Sagan's team wanted to include the Beatles song " Here Comes the Sun " on the record, but the record company EMI , which held the copyrights, declined. In the 1978 book Murmurs of Earth , the failure to secure permission for the song is cited as one of the legal challenges faced by the team compiling the Voyager Golden Record. In the book, Sagan said that the Beatles favoured the idea, but "[they] did not own the copyright, and the legal status of the piece seemed too murky to risk." When asked about the obstacle presented by EMI with regard to "Here Comes the Sun", despite the artists' wishes, Ann Druyan said in 2015: "Yeah, that was one of those cases of having to see the tragedy of our planet. Here's a chance to send a piece of music into the distant future and distant time, and to give it this kind of immortality, and they're worried about money ... we got this telegram [from EMI] saying that it will be $50,000 per record for two records, and the entire Voyager record cost $18,000 to produce." However, this was refuted in 2017 by Timothy Ferris; in his recollection, "Here Comes the Sun" was never considered for inclusion.

In July 2015, NASA uploaded the audio contents of the record to the audio streaming service SoundCloud .

In the upper left-hand corner is a drawing of the phonograph record and the stylus carried with it. The stylus is in the correct position to play the record from the beginning. Written around it in binary arithmetic is the correct time of one rotation of the record, 3.6 seconds, expressed in time units of 0.70 billionths of a second, the time period associated with a fundamental transition of the hydrogen atom . The drawing indicates that the record should be played from the outside in. Below this drawing is a side view of the record and stylus, with a binary number giving the time to play one side of the record—about an hour (more precisely, between 53 and 54 minutes).

The information in the upper right-hand portion of the cover is designed to show how pictures are to be constructed from the recorded signals. The top drawing shows the typical signal that occurs at the start of a picture. The picture is made from this signal, which traces the picture as a series of vertical lines, similar to analog television (in which the picture is a series of horizontal lines). Picture lines 1, 2 and 3 are noted in binary numbers, and the duration of one of the "picture lines," about 8 milliseconds, is noted. The drawing immediately below shows how these lines are to be drawn vertically, with staggered "interlace" to give the correct picture rendition. Immediately below this is a drawing of an entire picture raster , showing that there are 512 (2 9 ) vertical lines in a complete picture. Immediately below this is a replica of the first picture on the record to permit the recipients to verify that they are decoding the signals correctly. A circle was used in this picture to ensure that the recipients use the correct ratio of horizontal to vertical height in picture reconstruction. Color images were represented by three images in sequence, one each for red, green, and blue components of the image. A color image of the spectrum of the sun was included for calibration purposes.

The drawing in the lower left-hand corner of the cover is the pulsar map previously sent as part of the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11. It shows the location of the Solar System with respect to 14 pulsars , whose precise periods are given. The drawing containing two circles in the lower right-hand corner is a drawing of the hydrogen atom in its two lowest states, with a connecting line and digit 1 to indicate that the time interval associated with the transition from one state to the other is to be used as the fundamental time scale, both for the time given on the cover and in the decoded pictures.

Blank records were provided by the Pyral S.A. of Créteil , France. CBS Records contracted the JVC Cutting Center in Boulder, Colorado , to cut the lacquer masters which were then sent to the James G. Lee record-processing center in Gardena, California , to cut and gold-plate eight Voyager records. After the records were plated they were mounted in aluminum containers and delivered to JPL.

The record is constructed of gold-plated copper and is 12 inches (30 cm) in diameter. The record's cover is aluminum and electroplated upon it is an ultra-pure sample of the isotope uranium-238 . Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.468 billion years. It is possible (e.g. via mass-spectrometry ) that a civilization that encounters the record will be able to use the ratio of remaining uranium to the other elements to determine the age of the record.

The records also had the inscription "To the makers of music – all worlds, all times" hand-etched on its surface. The inscription was located in the "takeout grooves", an area of the record between the label and playable surface. Since this was not in the original specifications, the record was initially rejected, to be replaced with a blank disc. Sagan later convinced the administrator to include the record as is.