- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud Summary & Analysis by William Wordsworth

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

"I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" is one of the most famous and best-loved poems written in the English language. It was composed by Romantic poet William Wordsworth around 1804, though he subsequently revised it—the final and most familiar version of the poem was published in 1815. The poem is based on one of Wordsworth's own walks in the countryside of England's Lake District. During this walk, he and his sister encountered a long strip of daffodils. In the poem, these daffodils have a long-lasting effect on the speaker, firstly in the immediate impression they make and secondly in the way that the image of them comes back to the speaker's mind later on. "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" is a quintessentially Romantic poem, bringing together key ideas about imagination, humanity and the natural world.

- Read the full text of “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

The Full Text of “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

1 I wandered lonely as a cloud

2 That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

3 When all at once I saw a crowd,

4 A host, of golden daffodils;

5 Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

6 Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

7 Continuous as the stars that shine

8 And twinkle on the milky way,

9 They stretched in never-ending line

10 Along the margin of a bay:

11 Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

12 Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

13 The waves beside them danced; but they

14 Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

15 A poet could not but be gay,

16 In such a jocund company:

17 I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

18 What wealth the show to me had brought:

19 For oft, when on my couch I lie

20 In vacant or in pensive mood,

21 They flash upon that inward eye

22 Which is the bliss of solitude;

23 And then my heart with pleasure fills,

24 And dances with the daffodils.

“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” Summary

“i wandered lonely as a cloud” themes.

Nature and Humanity

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Memory and Imagination

Line-by-line explanation & analysis of “i wandered lonely as a cloud”.

I wandered lonely as a cloud That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd, A host, of golden daffodils; Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine And twinkle on the milky way, They stretched in never-ending line Along the margin of a bay: Ten thousand saw I at a glance, Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

Lines 13-18

The waves beside them danced; but they Out-did the sparkling waves in glee: A poet could not but be gay, In such a jocund company: I gazed—and gazed—but little thought What wealth the show to me had brought:

Lines 19-24

For oft, when on my couch I lie In vacant or in pensive mood, They flash upon that inward eye Which is the bliss of solitude; And then my heart with pleasure fills, And dances with the daffodils.

“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” Symbols

- See where this symbol appears in the poem.

“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Personification.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

Alliteration

Polysyndeton, “i wandered lonely as a cloud” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud”

Rhyme scheme, “i wandered lonely as a cloud” speaker, “i wandered lonely as a cloud” setting, literary and historical context of “i wandered lonely as a cloud”, more “i wandered lonely as a cloud” resources, external resources.

A Reading — The poem read by Jeremy Irons.

Daffodils at Ullswater — Photos and video of daffodils at the actual location mentioned in Wordsworth's account of the walk.

Nature and Wordsworth — A short BBC clip about Wordsworth's early relationship with nature.

Biography and other poems — A useful resource from TPoetry Foundation.

Preface to Lyrical Ballads — The preface to Coleridge and Wordsworth's 1798 book, Lyrical Ballads.

LitCharts on Other Poems by William Wordsworth

A Complaint

A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal

Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802

Expostulation and Reply

Extract from The Prelude (Boat Stealing)

It Is a Beauteous Evening, Calm and Free

I Travelled Among Unknown Men

Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey

Lines Written in Early Spring

London, 1802

My Heart Leaps Up

Nuns Fret Not at Their Convent’s Narrow Room

Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood

She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways

She was a Phantom of Delight

The Solitary Reaper

The Tables Turned

The World Is Too Much With Us

Three Years She Grew in Sun and Shower

To a Snowdrop

We Are Seven

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

What "Literal Meaning" Really Means

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

Pete Saloutos/Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Examples and Observations

Processing literal and non-literal meanings.

- 'What's the difference?'

- Literally and Figuratively

Distinction Between Sentence Meaning and Speaker Meaning

Lemony snicket on literal and figurative escapes.

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

The literal meaning is the most obvious or non-figurative sense of a word or words. Language that's not perceived as metaphorical , ironic , hyperbolic , or sarcastic . Contrast with figurative meaning or non-literal meaning. Noun: literalness.

Gregory Currie has observed that the "literal meaning of 'literal meaning' is as vague as that of 'hill'." But just as vagueness is no objection to the claim that there are hills, so it is no objection to the claim that there are literal meanings." ( Image and Mind , 1995).

" Dictionary definitions are written in literal terms. For example, 'It is time to feed the cats and dogs.' This phrase 'cats and dogs' is used in a literal sense, for the animals are hungry and it is time to eat. " Figurative language paints word pictures and allows us to 'see' a point. For example: 'It is raining cats and dogs!' Cats and dogs do not really fall from the sky like rain... This expression is an idiom ." (Passing the Maryland High School Assessment in English, 2006)

"The sea, the great unifier, is man's only hope. Now, as never before, the old phrase has a literal meaning: we are all in the same boat." (Jacques Cousteau, National Geographic, 1981)

Zack: "I haven't been to a comic book store in literally a million years." Sheldon Cooper: "Literally? Literally a million years?" (Brian Smith and Jim Parsons in "The Justice League Recombination." The Big Bang Theory, 2010)

How do we process metaphorical utterances? The standard theory is that we process non-literal language in three stages. First, we derive the literal meaning of what we hear. Second, we test the literal meaning against the context to see if it is consistent with it. Third, if the literal meaning does not make sense with the context, we seek an alternative, metaphorical meaning.

"One prediction of this three-stage model is that people should ignore the non-literal meanings of statements whenever the literal meaning makes sense because they never need to proceed to the third stage. There is some evidence that people are unable to ignore non-literal meanings... That is, the metaphoric meaning seems to be processed at the same time as the literal meaning." (Trevor Harley, The Psychology of Language . Taylor & Francis, 2001)

'What's the Difference?'

"[A]sked by his wife whether he wants to have his bowling shoes laced over or laced under, Archie Bunker answers with a question: 'What's the difference?' Being a reader of sublime simplicity, his wife replies by patiently explaining the difference between lacing over and lacing under, whatever this may be, but provokes only ire. 'What's the difference' did not ask for the difference but means instead 'I don't give a damn what the difference is.' The same grammatical pattern engenders two meanings that are mutually exclusive: the literal meaning asks for the concept (difference) whose existence is denied by the figurative meaning." (Paul de Man, Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust . Yale University Press, 1979)

"People have used literally to mean figuratively for centuries, and definitions to this effect have appeared in The Oxford English Dictionary and The Merriam-Webster Dictionary since the early 1900s, accompanied by a note that such usage might be 'considered irregular' or 'criticized as a misuse.' But literally is one of those words that, regardless of what’s in the dictionary—and sometimes because of it—continues to attract an especially snooty breed of linguistic scrutiny. It is a classic peeve." (Jen Doll, "You're Saying It Wrong." The Atlantic , January/February 2014)

It is crucial to distinguish between what a sentence means (i.e., its literal sentence meaning) and what the speaker means in the utterance of the sentence. We know the meaning of a sentence as soon as we know the meanings of the elements and the rules for combining them. But of course, notoriously, speakers often mean more than or mean something different from what the actual sentences they utter mean. That is, what the speaker means in the utterance of a sentence can depart in various systematic ways from what the sentence means literally. In the limiting case, the speaker might utter a sentence and mean exactly and literally what they say. But there are all sorts of cases where speakers utter sentences and mean something different from or even inconsistent with the literal meaning of the sentence.

"If, for example, I now say, 'The window is open,' I might say that, meaning literally that the window is open. In such a case, my speaker meaning coincides with the sentence meaning. But I might have all sorts of other speaker's meanings that do not coincide with the sentence meaning. I might say 'The window is open,' meaning not merely that the window is open, but that I want you to close the window. A typical way to ask people on a cold day to close the window is just to tell them that it is open. Such cases, where one says one thing and means what one says, but also means something else are called 'indirect speech acts.'" (John Searle, "Literary Theory and Its Discontents." New Literary History , Summer 1994)

"It is very useful, when one is young, to learn the difference between 'literally and figuratively.' If something happens literally, it actually happens; if something happens figuratively, it feels like it’s happening. If you are literally jumping for joy, for instance, it means you are leaping in the air because you are very happy. If you are figuratively jumping for joy, it means you are so happy that you could jump for joy, but are saving your energy for other matters. The Baudelaire orphans walked back to Count Olaf’s neighborhood and stopped at the home of Justice Strauss, who welcomed them inside and let them choose books from the library. Violet chose several about mechanical inventions, Klaus chose several about wolves, and Sunny found a book with many pictures of teeth inside. They then went to their room and crowded together on the one bed, reading intently and happily. Figuratively , they escaped from Count Olaf and their miserable existence. They did not literally escape, because they were still in his house and vulnerable to Olaf’s evil in loco parentis ways. But by immersing themselves in their favorite reading topics, they felt far away from their predicament, as if they had escaped. In the situation of the orphans, figuratively escaping was not enough, of course, but at the end of a tiring and hopeless day, it would have to do. Violet, Klaus, and Sunny read their books and, in the back of their minds, hoped that soon their figurative escape would eventually turn into a literal one." (Lemony Snicket, The Bad Beginning, or Orphans! HarperCollins, 2007)

- Figurative Meaning

- 5 Words That Don't Mean What You Think They Mean

- Definition and Examples of English Idioms

- Definition and Examples of Irony (Figure of Speech)

- Pragmatics Gives Context to Language

- Conversational Implicature Definition and Examples

- Figure of Speech: Definition and Examples

- Conceptual Meaning: Definition and Examples

- Get the Definition of Mother Tongue Plus a Look at Top Languages

- Word Words (English)

- What Is the Figure of Speech Antiphrasis?

- Understanding Subtext

- Complex Metaphor

- Are, Hour, and Our: How to Choose the Right Word

- What Are Tropes in Language?

Literal vs. Metaphorical — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Literal and Metaphorical

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, communication, effect on text, compare with definitions, metaphorical, common curiosities, what is metaphorical language, what does literal language mean, how do literal and metaphorical language differ in purpose, can you provide an example of literal language, can literal and metaphorical language be used together, in what contexts is literal language preferred, what's an example of metaphorical language, why is literal language important, what makes metaphorical language special, can metaphorical language be misunderstood, where is metaphorical language commonly used, how does one choose between using literal or metaphorical language, how does metaphorical language affect communication, is literal language devoid of creativity, what role does metaphorical language play in poetry, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

a large database of idioms

Understanding the Idiom: "walk the streets" - Meaning, Origins, and Usage

When we talk about someone who is “walking the streets,” what do we mean? This common idiom can have a variety of meanings depending on the context in which it’s used. It might refer to someone who is simply taking a stroll through their neighborhood, or it could suggest that they are looking for work or engaging in illegal activities.

Origins and Historical Context of the Idiom “walk the streets”

The phrase “walk the streets” is a common idiom used in English language to describe someone who is wandering aimlessly without any particular destination. This expression has been around for centuries and has its roots in various historical contexts.

One possible origin of this idiom dates back to medieval times when it was common for people to walk through the streets as a form of entertainment. During this period, there were no movies or television shows, so people would often gather on the streets to watch performers or listen to musicians. Walking through crowded city streets became a popular pastime, and eventually, the phrase “walk the streets” came into use.

Another possible origin of this idiom can be traced back to early modern Europe when prostitution was rampant in many cities. Prostitutes would often walk up and down busy streets looking for clients, hence giving rise to the term “walking the streets.” This usage of the phrase later evolved into a more general meaning of wandering aimlessly without any purpose.

In contemporary times, “walking the streets” has taken on new meanings related to homelessness and poverty. It is now commonly used to describe individuals who are forced to wander around urban areas due to lack of shelter or resources.

Usage and Variations of the Idiom “walk the streets”

When it comes to idioms, there are often variations in usage that can add nuance and complexity to their meanings. The idiom “walk the streets” is no exception, as it has several different ways in which it can be used depending on context.

One common variation of this idiom is to use it when referring specifically to a person who walks the streets as part of their profession. This could include individuals such as police officers, security guards, or even prostitutes. In this sense, “walking the streets” takes on a more literal meaning and refers to someone who spends time patrolling or working along a particular route.

Another way in which this idiom can be used is more metaphorical in nature. For example, one might say that they have been “walking the streets” looking for a job or trying to find inspiration for their art. In these cases, “walking the streets” means something closer to wandering aimlessly or searching for something specific.

Finally, there are instances where “walking the streets” can take on negative connotations. For instance, if someone says that they were forced to walk the streets after losing their job or being evicted from their home, it implies a sense of desperation and hopelessness.

Synonyms, Antonyms, and Cultural Insights for the Idiom “walk the streets”

One synonym for this idiom is “hit the pavement,” which means to walk around outside with no particular destination in mind. Another similar phrase is “pound the pavement,” which also implies walking with purpose but without a specific goal.

Antonyms for this idiom include staying indoors or being stationary. For example, one could say they are “cooped up at home” instead of walking the streets.

In some cultures, walking the streets may be seen as a leisurely activity, while in others it may be associated with homelessness or criminal behavior. Therefore, it’s important to consider cultural context when using this idiom.

Practical Exercises for the Idiom “walk the streets”

- Exercise 1: Vocabulary

In this exercise, you will be given a list of words related to walking and streets. Your task is to match each word with its correct definition.

- A designated area for pedestrians to cross a street safely.

- The act of crossing a street illegally or without regard for traffic signals.

- A hard surface that covers a road or sidewalk.

- A path alongside a road for pedestrians to walk on.

- Exercise 2: Grammar

In this exercise, you will practice using the idiom “walk the streets” in different tenses. Rewrite each sentence using the appropriate tense:

Present Tense:

“I am walking the streets of New York.”

“She walks the same route every day.”

Past Tense:

“He walked down Main Street yesterday.”

“We walked around downtown for hours.”

Future Tense:

“They will walk the streets of Paris next week.”

“I will be walking the same path as my ancestors did.”

- Exercise 3: Conversation Practice

In this exercise, you will practice using the idiom “walk the streets” in a conversation with a partner. Choose one of the following scenarios and take turns using the idiom to describe your experience:

- You are visiting a new city for the first time.

- You are taking a daily walk around your neighborhood.

- You are exploring an unfamiliar part of town with friends.

These exercises should help you become more confident in using the idiom “walk the streets” in everyday conversation. Remember to practice regularly and try to incorporate this expression into your English vocabulary whenever possible.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Using the Idiom “walk the streets”

When using idioms in language, it is important to understand their meaning and usage. The idiom “walk the streets” can be confusing for non-native speakers as it has multiple meanings depending on the context. However, there are some common mistakes that people make when using this idiom.

Mistake 1: Taking the Literal Meaning

The first mistake people make is taking the literal meaning of “walk the streets.” This idiom does not mean simply walking on a street or sidewalk. It actually means to wander aimlessly or without purpose, often implying that someone is looking for something specific.

Mistake 2: Using it Inappropriately

Another mistake people make is using this idiom in inappropriate situations. For example, saying “I walked the streets all night” might suggest that you were wandering around aimlessly with no destination in mind. This may not be appropriate if you were actually out with friends or had a specific destination in mind.

To avoid these mistakes, it’s important to understand how and when to use this idiom correctly. It’s also helpful to familiarize yourself with other similar idioms so you can choose the right one for each situation.

- Instead of saying “I walked the streets,” consider saying “I wandered around town.”

- If you want to imply that someone was searching for something specific while walking around, try saying “He was pounding pavement all day.”

- Remember that idioms are not always meant to be taken literally.

By avoiding these common mistakes and understanding how to use this idiom properly, you can effectively communicate your message without confusion or misunderstanding.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Terms and Conditions

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of wanderlust

Did you know.

Wanderlust Has German Roots

"For my part," writes Robert Louis Stevenson in Travels with a Donkey , "I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel's sake. The great affair is to move." Sounds like a case of wanderlust if we ever heard one. Those with wanderlust don't necessarily need to go anywhere in particular; they just don't care to stay in one spot. The etymology of wanderlust is a very simple one that you can probably figure out yourself. Wanderlust is a lust for wandering. The word comes from German, in which wandern means "to hike or roam about," and Lust means "pleasure or delight."

Examples of wanderlust in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'wanderlust.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

German, from wandern to wander + Lust desire, pleasure

1875, in the meaning defined above

Theme music by Joshua Stamper ©2006 New Jerusalem Music/ASCAP

Get Word of the Day delivered to your inbox!

Dictionary Entries Near wanderlust

Cite this entry.

“Wanderlust.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/wanderlust. Accessed 9 Sep. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of wanderlust, more from merriam-webster on wanderlust.

Nglish: Translation of wanderlust for Spanish Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, 31 useful rhetorical devices, more commonly misspelled words, absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

There are no comments.

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of literally adverb from the Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

Join our community to access the latest language learning and assessment tips from Oxford University Press!

- 3 ( informal ) used to emphasize a word or phrase, even if it is not literally true I literally jumped out of my skin. Although this is a common use of literally , some people think it is not correct.

Nearby words

What is the literal meaning of the following quote? "I have heard related / that such a pair they have sometimes seen, / march-stalkers mighty the moorland haunting, / wandering spirits." There are terrorists loose in the city. People are sleep-walking at nights all over the land. People have seen mysterious figures walking in the moors. People are being stalked.

Gauth ai solution, super gauth ai, explanation.

The womb as a wild mother beast

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2024

- Volume 15 , pages 301–328, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Naama Cohen-Hanegbi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3854-5853 1 &

- Guy Erez 2

This article traces the roots of a metaphor that compares the aching womb to a forest or wild beast. A close examination of the metaphor, which appears in a chapter on uterine pains in Gilbert of England’s Compendium medicinae, opens a window into ideas that circulated in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Latin thought about human and animal maternal affection. After mapping out the medical tradition in which this singular metaphor appears, we turn to bestiaries, encyclopedias, literature, biblical commentaries, and sermons to situate this metaphor in a broader cultural context. By awakening the metaphor of the wild beast/womb, we identify a notion of embodied motherly love that circulated in medieval learned Latin Europe. These findings, in turn, shed new light on the role of animal-human discourse during the period, and reveal a compassionate approach to miscarriage and loss within medieval medicine.

Explore related subjects

- Medical Ethics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As for pain of the womb after birth: Pain of the womb happens often due to a premature miscarriage; for [the womb] suffers from the loss of that which delights it, because its nature is to propagate its kind. Therefore, it is moved like a wild beast ( ad modum fere slivestris ) searching for its missing fetus. For the womb delights most in embracing, holding onto and nourishing it. (Gilbertus Anglicus 1510 , fol. 308r). Footnote 1

These short but powerful lines are taken from the seventh book of the Compendium medicinae in which the thirteenth-century physician, Gilbert of England (c.1180-after 1250), assembled information on malaise of the genitals. The metaphor of the womb as a wild beast that opens this chapter is surprising in its tone and content, particularly in view of the systematic and technical, often dry, approach of the Compendium . It portrays the womb as an active, animated organ with independent sensations and emotions and a motherly attachment to the fetus. The metaphor is unique: more common reproductive images were of the womb as receptive and stationary, using vegetative analogies. While the wild beast metaphor may recall other, better known ideas about the womb’s unruly animality, Gilbert presents a more concrete and notably positive view of the womb’s sensitive powers. In an effort to ‘wake up sleeping metaphors,’ as anthropologist Emily Martin ( 1991 ) encourages us to do, that is, to trace the origins of this metaphor and the meaning it enveloped, this essay draws attention to little known ideas about the womb, emotions, and maternity that circulated in medieval medicine and culture. By contextualizing this metaphor within the vibrant discussions on animals in medieval traditions, we further point to a prevalent discourse of ferality as innately associated with uncorrupt divine nature, contributing to the ongoing debate about medieval human-animal hierarchies in current scholarship on animal studies.

In her seminal essay ‘The Egg and the Sperm,’ Martin dissected modern scientific and popular accounts of reproductive biology demonstrating their reliance on cultural stereotypes (Martin 1991 ). Through a survey of word choices and metaphors, Martin demonstrated the infiltration of biases into twentieth-century descriptions of biological processes and an ongoing tendency to ascribe archetypal gendered roles to female and male reproductive systems even while scientific theories developed and changed. For example, in depicting the egg as aging and menstruation as waste, but sperm as energetically reproductive, the biological language reaffirmed stereotypical expectations of female/male behavior and contributed to their naturalization. Notably, she found that the main characteristics of the egg shifted between seeing it as waiting passively to be fertilized to acting aggressively towards this goal: quite comparable to the two metaphors of the womb in premodernity as mentioned above. But medieval thought was not as binary as it is often depicted. Gilbert’s analogy and its contextualization provides evidence to an assortment of womb metaphors in the period; metaphors that diverged from the typical passive container or the harmful creature.

Similar proliferation may certainly be found in twentieth-century biology as well, but Martin focused on popular accounts, across a spread of genres and media, from scientific articles to textbooks and films in order to identify a salient cultural phenomenon. In this respect our focus is necessarily different. It is difficult to assess how far Gilbert’s analogy was disseminated. Gilbert’s work was copied, translated, and read, and there is no doubt it influenced the writings of other physicians, such as the Florentine Niccolò Falucci (d. 1412), and even Chaucer’s fictional Doctor of Physick (Green 2005 , 196). However, while the metaphor appears in all extant copies and translations of Gilbert’s treatise, the precise metaphor does not reappear in other authors’ works. Footnote 2 Little is known of Gilbert. His name indicates that he was probably born in England, and it is also likely that he studied and taught medicine at the University of Montpellier (McVaugh 2010 ). The Compendium (published in 1250) belongs to a genre of practice oriented medical literature that encompassed information on treatments of all illnesses ‘from head to toe’ and was well rooted in the period’s learned approach to medical care on the whole, and to gynecology more specifically (Demaître 2013 , 27–28). The quasi-poetic use of similes is, however, rare within the functional, dry, and direct language that characterizes the work and its parallels. In this respect, too, it cannot be argued that Gilbert’s metaphor is a common trope. Yet, while the resonance of his view cannot be attested, we assume that Gilbert’s metaphor, as is the case for any linguistic choice, is a mirror to the culture that bore it (Schiebinger 2004 , 23–28). That is, we see the novel use of this metaphor as a gateway to uncovering fundamental shifting attitudes toward maternity, emotions, and animality circulating in Gilbert’s own cultural environment.

We therefore aim to unpack the metaphor, asking: Why did Gilbert choose to compare the womb to an animal? Why, more specifically, is a ‘forest animal’ or ‘wild beast’ the metaphor chosen to describe the empty womb? Why is the described pain conceptualized in language of delight and sorrow? And why turn to animal imagery to describe the emotional relationship between the womb and the fetus? Answering these questions lays forth a metonymic relationship between womb and mother; an association between motherhood, love, and the meaning of carrying a fetus and child in various forms of literature in twelfth- and thirteenth-century western Europe. Demonstrating that these cultural notions imprint onto scientific knowledge sheds light on medical discourse on miscarriage and, more importantly, it shows one avenue through which this web of ideas became naturalized (see Jordanova 1993 ).

The animal womb and the fetus fruit

Depictions of the womb as having animal attributes appear in a number of influential texts by Plato and Hippocrates (King 1993 ; Dasen 2002 , esp. 172). The vast scholarship on hysteria and on hysterikē pnix (suffocation of the womb) has shown that in this early literature the womb was often understood to have monstrous and kinetic abilities, at times even to act like an actual animal living within the body. In most of these texts the animal characteristics are vague, offering no specific identification of its nature (Faraone 2011 ; Arnaud 2015 ). Upon examining talismans alongside medical treatises produced in Classical Greece, scholars have suggested that the womb became associated with the octopus due to both their physical and functional resemblance (Freidin 2021 ). Looking ahead to the European Middle Ages, the notion of the animal womb seems to have waned. The most influential medical authors of gynecological treatises, Galen and Soranus, writing in the first and second centuries, insisted that despite some slight motor ability, the womb was unable to move through the body. In the words of Soranus: ‘For the uterus does not issue forth like a wild animal ( therion ) from the lair’ (Soranus trans. from Greek by Temkin 1991 , 153; see also Green 2001 , 22–31). This clear position did not completely abolish the notion of the womb as having a life of its own. Through the Middle Ages, partly due to Muscio’s influence, some authors noted that in cases of suffocatio matricis (suffocation of the womb) the uterus might leave its place and shift upwards towards the throat and head, or that it would at least expel harmful vapors in this upward direction (King 1993 , 47–49; 55–56). Still, animals or animal characteristics are not included in the chapters devoted to this illness, neither to describe nor analyze its manifestation.

Gilbert’s metaphor, then, does not correspond in any apparent way to the discourse on the suffocation of the womb, except in that it repeats Soranus’ rejected identification of the womb as a wild beast. Gilbert was not the first to adopt Soranus’ analogy in an inverted way. Although the transmission of Soranus’ work involved considerable changes of text throughout the Middle Ages, and the Latin translation of the chapter mentioning the wild beast does not seem to have survived, the metaphor reappears in another medical text (Soranus 1882 , 1951 ; Green 2001 , 30). A chapter on ‘the pains of the womb’ in one of the gynecological texts, which circulated under the title of Trotula —ascribed to the twelfth-century Salernitan physician Trota— De curis mulierum ( On Treatments for Women ), employs this same beast metaphor (see Green 2000 , 2008 , 82–83). Uterine pains occur, the text explains, when ‘The womb, as though it were a wild beast of the forest ( fera silvestris ), because of the sudden evacuation falls this way and that, as if it were wandering’ (Green 2001 , 118–121). There is no doubt that Gilbert relied on this chapter when writing his own. Both chapters discuss uterine pains, and both compare the womb to a forest/wild beast. Yet, equating the two passages highlights Gilbert’s unique intervention. While for Trota the metaphor elucidates the womb’s physical reaction to the process of emitting the fetus, Gilbert utilizes the beast metaphor to expound on the nature of this reaction. Footnote 3 In his rendition of the chapter, the emphasis is not on the tilting motion per se , or what perhaps describes uterine prolapse, or severe cramps, but on the emotions involved in the process of pregnancy and miscarriage. As shall be demonstrated below, this new emphasis shifted the meaning of the metaphor in a way that resonated with contemporaneous attitudes towards animality and maternity.

A less dramatic, but in fact longer-standing metaphor for explaining the womb’s behavior was vegetal rather than animal. Such a metaphor appears, for example, in De sinthomatibus mulierum ( Book on the Conditions of Women ), another treatise that forms part of the Trotula cluster, but was written, according to Monica Green, by an educated male physician versed in the Latin medical knowledge of the period. Discussing the care of the pregnant woman and the preservation of the fetus, he wrote:

Galen reports that the fetus is attached to the womb just like fruit to a tree, which when it proceeds from the flower is extremely delicate and is destroyed by any sort of accident. But when it has grown and become a little mature and adheres firmly to the tree, it will not be destroyed by any minor accident. And when it is thoroughly mature it will not be destroyed by any mishap at all. (Green 2001 , 98–99)

The comparison of the fetus to fruit recurs in another medical treatise from roughly the same period, Le régime du corps ( Regimen of the Body ) written by Aldebrandin of Siena (d. c. 1287) for Princess Beatrice of Savoy in the second half of the thirteenth century. There, too, the vegetative analogy appears to highlight the need for caution during the first months of pregnancy in order to avoid miscarriage. The fetus in these first months, Aldebrandin explained, is fragile like a young fruit that ‘falls because of little wind or rain,’ but when ‘it ripens—it will fall gently like a flower’ (Aldebrandin de Sienne 1911 , 71). The growth and natural ripening of a fruit offers a model for comprehending the development of the fetus in the womb, both with regard to the dangers to which the fruit/fetus are susceptible and to the process of maturation.

In contrast to the singular use of the animal analogy, the vegetative analogy has numerous precursors in core medical texts read in the medieval period. The Hippocratic treatise ‘Nature of the Child’ includes a long botanical discussion, which seems to deviate from the original theme of the treatise—pregnancy and childbirth (see Holmes 2017 , esp. 363). The author turns to a detailed explanation of the way in which a plant acquires the necessary humidity and nutrients from the ground, and grows through the accumulation of these essential materials (Hippocrates trans. from Greek by Potter 2012 , 61–79). This process of formation through absorption of nutrients is presented as a coherent analogy for the development of the fetus, and the author states clearly that any person examining these issues will discover that ‘the growth of things from the ground and human growth are completely parallel.’ (Hippocrates trans. from Greek by Potter 2012 , 79). Additional metaphors that compare the fetus to a cucumber in a glass jar, or to a tree growing close to a stone, appear in other parts of the treatise to explain and exemplify how poor surroundings may corrupt the development of the fetus, in the same way that a plant or a fruit would be spoiled by growing in unsuitable surroundings (Holmes 2017 , 362).

The botanical analogy also appears in the writings of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) on animals, in particular in his De generatione animalium ( On the Generation of Animals ). In several instances, Aristotle describes the development of the fetus by comparing it to the growth of a plant in the ground, starting with the way semen is absorbed in the womb or the ground, and continuing with the guiding principle that directs its development and the ways in which it accepts its nutrients from its surroundings (see Aristotle trans. from Greek by Peck 1953 , 193, 197, 199, 457). Both Aristotle and the Hippocratic author blur the boundaries of the analogy between plant and fetus to a degree that it becomes uncertain whether the development of the plant is a useful, even precise, model for the development of the fetus, or if the fetus in the womb is in fact an actual vegetative growth. Alongside the recurrent reference to plants as an explanatory tool, Aristotle claims that in the primary stages of development, animals not only behave like plants, they ‘live the life of plants’ (Aristotle trans. from Greek by Peck 1953 , 491; Connell 2016 , 128–129).

This recurring notion of the womb-as-vegetal is also evident in the twelfth-century Salernitan anatomical text, Anatomia porci Cophoni s ( Copho’s Anatomy of the Pig ) which uses the botanical analogy to describe the physical form of the womb of a sow: ‘This organ [the womb] is a natural field that is sown and bears fruits’ (trans. from Latin by Corner 1927 , 50). Footnote 4 In the Book on the Conditions of Women , too, the use of the fruit as a model for the fetus exemplifies the mixing of analogical and verbal hermeneutics: ‘But when the soul is infused into the child, it adheres a little more firmly and does not slip out so quickly’ (Green 2001 , 98–99). This view of the role of the soul seems to rely on Galen’s theory regarding the development of the intellectual soul—the perception that before a fetus develops cognitive abilities it is a vegetal growth in every sense (see Hanson 2008 ; Flemming 2018 ).

Albert the Great’s (c.1200–1280) thirteenth-century work De animalibus ( On Animals ) demonstrates further the concrete sense that the botanic analogue came to assume. Albert described the structure of the womb using botanical terminology, suggesting that the fetus was connected to the womb through cotyledons —that is, the tendons that connect the fruit to the tree. Again, the lexical transfer implies that the workings of the womb and the plant are not only analogous or similar, but identical (Albertus Magnus 1916 , 702; see also Flemming 2018 , 102). There is, therefore, a recurring tendency in these examples of descriptions of the womb and fetus as plants or fruits to blur the line between analogy and actual processes. More importantly for our purposes, in all previous examples the vegetal model was taken as embodying the normal, expected behavior of women’s reproductive organs. Gilbert and Trota describe a state of distress for which the placid, stationary depiction of the womb as soil or jar did not suffice.

Medical use of animal imagery

Animals are frequently used to describe disorders, illnesses, and symptoms of maladies in medieval medical treatises. They are evoked as descriptive aids for specifying manifestations of disease, for example, tumors are firm and round like a cancer (Latin for crab), or they metastasize and resemble its feet. Animal imagery is even more effective for describing the behavior of disease: the disease clings to the body, spreads within it, and bites into it like a cancer, or a hungry wolf. Sores on the face and feet were identified as lupus , and various kinds of leprosy were classified according to the physical resemblance or complexional similarities to these animals—namely, elephants, lions, snakes, and foxes ( elephantia, leonina, tyria, alopecia ). In some extreme cases, the sick would be described as turning themselves into animals due to their illness. In particular, rabies patients were considered to be in danger of assuming canine behavior (Walker-Meikle 2021 ). Marie-Christine Pouchelle and Luke Demaître suggested that animal metaphors were used as part of the descriptions of ailments in order to accentuate the threat the disease posed and the fear and suffering it caused. Accounts of illnesses mention animal traits to denote physical or cognitive symptoms, for example, the skin may turn scaly and snake-like, or a manic episode may result in animal-like behavior, such as crowing like a rooster (Pouchelle 1990 , 173–175; Demaître 1998 ). These didactic comparisons could potentially develop into actual materia medica . Alongside prescriptions based on humoral qualities of various animal parts, numerous recipes call on the metaphorical force of curing like with like, such as consuming testicles of oxen, wolves, or dogs for overcoming sterility (Guglielmo da Varignana 1520 , fols. 69–70).

The visceral nature of animal metaphors, as opposed to the more learned and detached vegetal descriptions, may explain why Trota and Gilbert chose it to describe the womb’s behavior following a traumatic event, for example, ‘following a sudden evacuation’ ( propter subitam evacuationem ) (Green 2001 , 118) as in the De curis mulierum ( On Treatments for Women ), or ‘because of premature miscarriage’ ( ex aborsu ante tempus ) (Gilbertus Anglicus 1510 , fol. 308r). The forest beast appears to emphasize that the womb is in a state of distress. The decision to use animal imagery to emphasize the nature of the pains of the womb requires the metaphor to be read in the context of animal imagery within medieval Latin medical literature, as discussed above. Still, while it is clear that the authors relied on the period’s cultural discourse and cultural representations of animal behavior as indicative of malaise, Trota’s and Gilbert’s animal imagery is peculiar in several notable ways. First, rather than defining the malaise or symptom in their texts, the animal defines the behavior of the body part (Walker-Meikle 2021 , 88). Second, in contrast to the more prevalent allusion to specific animals, Trota and Gilbert provided a general metaphor that refers to a broad category of animals, suggesting that their emphasis is on the disparity between human and animal reactions. Third, in both cases, but arguably more clearly in Gilbert, the animal metaphor elucidates emotional or mental stress in addition to physical pain. Finally, in contrast to most animal imagery, here the animal is not violent as is more often the case. The beast-womb does not ‘bite’ the body or attack it, as in other illnesses, nor does it pressure or suffocate the woman, as it may appear in classical discourse on the wandering womb (Pouchelle 1990 , 168; Dasen 2002 , 182). De curis mulierum ( On Treatments for Women ) uses the animal metaphor in the opposite way: the beast is conjured to explicate the pain inducing movement of the womb. Footnote 5 Gilbert expanded the metaphor further, describing the loving relationship of the womb towards the fetus, thereby highlighting the emotional distress involved in losing it (Cohen-Hanegbi 2019 , esp. 125–127). In Gilbert’s own words, the womb ‘mourns the absence’ (Gilbertus Anglicus 1510 , fol. 308r). The animal metaphor comes to signal the maternal function of the womb.

Attempting to contextualize the forest beast analogy solely within the medical tradition leads to partial comparisons, as the imagery is distinct from other womb analogies and other uses of animal imagery in medical texts. The forest beast might be better understood within a wider set of medieval discussions on animals and their similarity to people, particularly women, found in twelfth- and thirteenth-century natural philosophy, literature, bestiaries, and so on. It is impossible to comprehensively survey this literature here, yet the few examples below will help demonstrate that stories and images of wild beast mothers permeated Gilbert’s contemporary culture and thus enrich our understanding of his metaphor of the womb as a mourning wild beast.

On animals and parenting

Analogies between humans and animals were widespread in medieval literature. While often mocking human pettiness and immorality, these analogies offered an attentive contemplation on human nature, habits, and behavior (Salisbury 2022 , 149). Childbirth, paternal roles, and in particular maternity and maternal nurturing were illuminatingly dissected through descriptions of animals and human-animal family relations. Animal nursing of human babies was a recurring trope: Remus and Romulus were nursed by a wolf, a bear raised Orson in the French romance Valentin et Orson , and in the moralizing Renart le nouvel ( The New Reynard ) a pig nursed a child whose wet nurse’s milk had dried up (Giélée de Lille 1874 , 450–451). Despite the perilous milk, in such legends the feral nature of beasts could become a beneficial source of strength, endowing the human children with the inhuman powers of the beasts, turning them into strong, valiant heroes. Footnote 6 Underlying the fascination with ferality was the concern over human maternal carelessness and neglect. These feral children, despite being uncivilized, had complex affective relationships with their animal parents (see Steel 2019 , 41–74, esp. 60–61). In some cases, the animals are even portrayed as better than the human parents or caregivers (Dittmar, Maillet, and Questiaux 2011 ). In Renart le nouvel , for example, the sow takes to feeding the child instinctively. Whereas the relationship between the wet nurse and the child is strained, and the biological parents of the child are missing from the story altogether, the relationship between the infant and the animal is depicted as natural and powerful to the extent that the child ultimately adopts pig-like mannerisms (Dittmar, Maillet, and Questiaux 2011 ). This vigorous force of animal attachment is further visible in the fourteenth-century French chanson de geste Lion de Bourges , in which the lioness ‘died of sorrow for the love of the infant’ having being separated from the abandoned human child she raised and nurtured (Kibler 1980 , 21).

A similar contrast between human abandonment and animal nurture can be found in the romance La naissance du chevalier au cygnet ( The Birth of the Swan Knight ), which connects the ancestry of the crusader Godfrey of Bouillon (1060–1100) to the swan-knight and tells of a doe that nursed one of his paternal ancestors who, along with his brothers, was abandoned by his mother (Nelson 1977 , 147). Together with the hermit who found them in the woods, the doe, the beast of the meadow ( bieste de prés ), tends to the children immediately, feeding them with her milk and caring for them until maturity. According to one of the versions of this narrative, one day one of the children, having spent most of his life under the odd couple’s care, asks the hermit: ‘What is a mother? Is she some kind of foodstuff? Does she look like a bird or a beast? I have never seen one.’ The hermit responds: ‘Son, [a mother] is a woman that carries you in her womb’ (quoted and translated in McCracken 2013 , 44).This biological answer reaffirms the act of carrying a child in the womb as defining the essence of maternity, but these stories all make clear that animals could challenge the idea of human maternity, and even supersede it in the literary imagination.

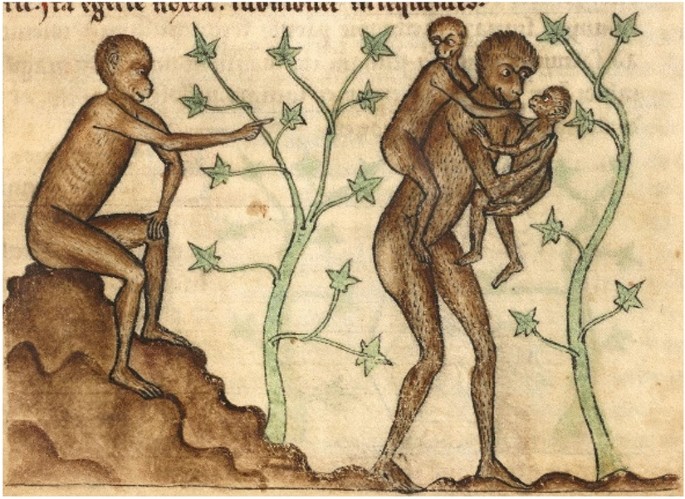

Bestiary literature of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries offered another sphere for a detailed meditation on the biological nature of maternal affection. The female ape ( simia ), for example, was often employed as an emblem of foolish motherhood. In The Aberdeen Bestiary, the ape is described as giving birth to twins, one of whom she loves and the other she hates. When the ape is forced to flee from a hunter, she places the hated ape-child on her back while hugging the loved one to her bosom (Fig. 1 ). However, this strategy works to her detriment because when she tires from the running and is unable to stand up straight, she ends up dropping the loved child (The Aberdeen Bestiary, MS 24, fol. 12v). Other animals, in contrast, could exemplify ideal forms of motherhood. In The Aberdeen Bestiary, the female tiger, for example, loves all her offspring dearly and chases any hunter who tries to capture her cubs. Her love of her offspring is so strong, that if the hunter throws a mirror in front of her, she will mistake her reflection for her child and try to nurse it. When she comprehends her mistake she resumes her chase, but again, when another mirror is thrown in her direction, she repeats the same error (fol. 8r.).

© Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. CC-BY-NC 4.0

A female bear licking her unformed cub. Bestiary . Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 764, fol. 22v.

The alluring images of the animals and their cubs added to the amusement of intended readers, whether of monastic affiliation (see Cordonnier 2021 ) or courtly or wealthy stature (see Grollemond 2019 ; Hassig 1990 – 1991 ). These accounts of animal maternal behavior also appear in other zoological writings, such as the encyclopedias of the thirteenth century, and through them they circulated widely (see Cohen 1994 ). Thomas of Cantimpré’s (1201–1272) De natura rerum ( On the Nature of Things ), for example, informs us that horses love their offspring more than any other animal, ewes can identify the smell of their lambs among all others, and sea cows, which are hot-tempered, easily angered animals, usually raise one child at a time over the duration of ten years (Thomas Cantimpratensis 1973 , 133). During this time, the sea cow feeds and tends to her young wherever they might go, carrying them with her because she loves holding them ( quia tenere diligit eum ) (Thomas Cantimpratensis 1973 , 248). As in the previous cases, carrying and holding are expressions of love and care. Within these various anecdotes there is no direct parallel for Gilbert’s metaphor; nevertheless, together they do suggest that for twelfth- and thirteenth-century readers it was commonplace to consider a wild beast as epitomizing intuitive maternal care.

Intuitive maternal care was not considered to be found equally in all animals. According to Aristotle, in his On the Generation of Animals , parental care and love correlated with mental faculties. While the simplest animals care and nurture their offspring only until they give birth, more developed animals care for their newborn until it is clear that they have developed properly. Those with even more developed reasoning accompany their offspring until the growth phase ends: ‘Those which are endowed with most intelligence show intimacy and attachment towards their offspring even after they have reached their perfect development’ (Aristotle trans. From Greek by Peck 1953 , 289). This link between cognition and affection resonated among Christian authors, yet with a notable shift. Humankind diverged sinfully from the divinely ordained order of things, distorting their own natural inclination, whereas animals act according to the fundamental laws of creation (Smith 2011 , 17).

The influential Hexameron , Ambrose’s (c. 339–397) commentary on Genesis, written in the fourth century, demonstrates this vividly. Footnote 7 For Ambrose, animal behavior was instructive. Animals exemplify a host of good traits and deeds: for example, ants are willful and practical, and one may follow their ways to avoid sinful sloth, and the barking of dogs wishing to protect their lords calls upon humankind to ‘bark’ for the sake of the Lord (Ambrosius 1845 , col. 248). Animals’ natural instincts are most apparent in their parental habits. The ewe’s developed sense of smell that allows her to identify her offspring serves as a model for the good pastor (and by extension, the good person) whose senses are often too dull to notice the most basic things. Humankind’s instincts are not sharp enough. Thus, the ewe can single out her own progeny ‘through her parental love alone. The shepherd errs in distinguishing the lambs, the lamb is unable to misrecognize their mother. The shepherd is deceived by kind, but the ewe is guided by affection. It would seem to all that all [lambs] have the same smell, but nature bestows upon them the ability to discern the smell of their offspring’ (Ambrosius 1845 , cols. 251–252). Even more astounding is the female bear: ‘Although all scriptures warn that she is a deceitful feral animal, when she gives birth to unformed infant-bears, she licks them into shape with her tongue’ (Fig. 2 ). Ambrose continues to explain the moral of this surprising phenomenon: ‘Would you not wonder that such a wild creature should express such charity with her mouth? The female bear sculptures her own form in her newborn, how can you not give your own children your likeness?’ (Ambrosius 1845 , col. 248). Footnote 8

Illustration of the ape with her children. De natura animalium . Bibliothèque Municipale de Douai, MS 711, fol. 8r. Droits libres under Loi Lemaire 2016

With these and similar stories Ambrose asserted that beasts ( bestiae ) are endowed with a natural parental instinct that instructs them to love their offspring and care for them, but humankind must receive specific ethical guidance for maintaining worthy familial relationships (according to the words of Paul to the Colossians 3:21–22; Ambrosius 1845 , col. 250). Ambrose was particularly concerned with family intrigue resulting from marriage, such as the desertion of children from previous marriages, or forgetting one’s nuclear family once one is married. Such problems, he confirmed, do not occur among wild beasts. In fact, Ambrose goes as far as to state that the less rationality a creature receives from God, the more loving and affectionate that creature becomes—a statement whose full ramifications are considered below. This love renders female animals ready, whenever needed, to die to save their offspring. The animals that nurse children in medieval romances echo this point and take it further, suggesting that the exemplary role of animals in matters of parenthood, and especially maternity, endured and gained new meanings beyond Ambrose’s sermons. Animals were not only better natural parents to their own offspring, but to human children as well, thereby connecting a bestial nature with ideas of proper and essential maternal behavior that is invariably inspired by divine creation.

This perception of animals as exemplars of parenthood, and specifically motherhood, is easily located in bestiary literature and medieval theology, but it found its way into medical literature as well. Hildegard of Bingen’s (1098–1179) Physica demonstrates the cross-disciplinary nature of nonhuman motherhood. The text, which has a distinctly medical orientation (it is primarily devoted to remedies for bodily ailments) nonetheless shares many similarities with bestiary literature, as Hildegard looks to animal behaviors to understand their beneficial or harmful properties as materia medica (Van Dyke 2018 , 109, 113). In Hildegard’s descriptions, as Carolynn Van Dyke has shown, motherhood and nurture take center stage as the way to understand animal behaviors. Hildegard focuses on the creatures’ emotions and empathizes with them, so as to help the reader understand the connections between people and other animals (Van Dyke 2018 , 112, 115). Thus, to demonstrate the bear’s inherent heat, or passionate nature, which makes its flesh unfit for human consumption, Hildegard repeats Ambrose’s account of the Mother Bear (preceded in turn by quotations from Ovid and Pliny, among others), but she expands it to include further medical concepts and ideas, as well as to offer an emotional commentary on the bear’s actions. To the idea that bear cubs are born unformed due to the short, month-long, pregnancy of bears (see, for example, Isidore of Seville 2006 , 252–253), Hildegard adds:

When the bear conceives she is so impatient in childbirth that, in her impatience, she aborts before the cubs within her have come to maturity. Although they receive vital air in their mother, they do not move within her. When she gives birth, she pours out something like flesh that, though it has vital air within it, does not move; it does have all the exterior features of its shape. Seeing this, the mother grieving, licks it, passing her tongue over all its features until all its limbs are distinguished. (Hildegard von Bingen, trans. from Latin by Throop 1998 , 209). Footnote 9

Hildegard’s intention to explain the odd account of the bear’s parturition in as natural terms as possible is apparent here. First, she stresses that the newborn cubs are alive both inside and outside the womb, despite their immobility. Her decision to add the physiological term ‘vital air’ emphasizes that the bear does not revive her cubs and that no magical or unnatural action is involved. It is a choice that enhances the natural probability of the account over its more mythic aspects. Second, Hildegard presents an emotional explanation for the moment of birth in ascribing to the bear impatience, and later grief, over her unformed cubs. Footnote 10

Hildegard’s Physica provides a supplementary example of the web of associations and metaphors we study here. The Physica cannot be considered part of the gynecological tradition that stands at the center of our discussion; in fact, it cannot be defined as a professional medical work per se. Its engagement in various general discussions on the nature of creation points to its correspondence with earlier writings on nature, such as those of Ambrose of Milan or Isidore of Seville, both with respect to content and to the intellectual conditions of its writing. In addition, in contrast to the writings of Ambrose and Isidore, the Physica ’s impact on later works appears to have been extremely limited.

There is, however, ample evidence of additional medical literature that draws connections between animals’ maternal behavior and their medical properties, including, in most concrete forms, the application of animal organs in medication. As early as the fourth century BCE, Aristotle reported that the afterbirth of a mare was an extremely sought-after substance among pharmacists and sellers of materia medica . He added that the afterbirth was especially difficult to obtain because mares tend to eat it quickly after giving birth, and if they sense someone attempting to take it, they will become extremely wild (Aristotle trans. from Greek by Peck 1970 , 325–27). The use of humans’ and animals’ afterbirth as a remedy is well-known. In the thirteenth century, the most important commentator on Aristotle, Albert the Great, elaborated on this practice and added that the particular use of the mare’s hippomanes (a substance that forms in the mare’s allantois) was an ingredient in an ointment for arousing parents’ affection for their children: ‘And women enchanters, when they are able to get hold of the [mare’s afterbirth], they whisper some enchanted charm through which they make parents love their infants’ (Albertus Magnus 1916 , 545). The logic behind this charm is that of curing like with like: just a few chapters earlier, Albert highlights the mare as singular among the animals for its love towards its offspring, repeating Aristotle’s observation of the natural maternal devotion of these animals (Aristotle 1970 , 239). Footnote 11

Susan Crane suggests that the descriptions of animals and their behavior in the bestiaries were meant to illustrate how humans and nonhumans relate and differ from each other ( 2008 , 7). As she and others note, appeals to human-animal similarities often served to naturalize cultural phenomena, especially in regard to gender. By likening women and men to animals, writers presented specific ideas about gender as part of God’s nature (Crane 2008 , 28; see also Van Dyke 2018 , 98). In the case of medieval discussions of animal maternity, this process of naturalization is especially apparent: the relationship between mother and child is identified in nonhuman animals and idealized. In some cases, as we move from literature and the bestiary towards medical texts, we see that this process is not just figurative but literal, embodied in the organs with which maternity is associated. Through consuming the mare’s hippomanes , soaked in the animal’s nature, parents could strive towards the ideal of love towards their newborn. This cure expresses in a performative way the immense impact of analogy, which does not remain solely in the realm of ideas but becomes realized and concretely useful in the external world.

The womb metaphor employed by Gilbert follows a similar logic, as it seeks to naturalize the often-traumatic state of miscarriage. In a way, this naturalization is similar to the use of vegetal metaphors in gynecological texts that present pregnancy as as natural as the growing of trees and fruit. At the same time, however, the usage of an animal metaphor highlights what the vegetal metaphor lacks: the emotional aspects of pregnancy, miscarriage, and pain to which we now turn.

The language of metaphor: Fera silvestris

So far, the discussion suggests that it is the bestiary tradition and other medieval discussions of animals that can provide a useful context for understanding Gilbert’s metaphor rather than medieval medical literature. The passage in the Compendium echoes a view of animals that prioritizes their emotional lives and their meaning as behavioral instructors for human readers and not an interest in animal bodies as a model for how diseases might operate or how bodily processes occur. This is not just a question of similar attitudes, however. It is important to contextualize Gilbert’s work outside of the medical tradition to examine the way his metaphor conceptualizes the animal as a fera silvestris (‘wild beast’) and how it could have been interpreted by his contemporary audience.

It is certain that Gilbert borrowed fera silvestris from his predecessors: most immediately, Trota, and, going farther back, Soranus’ Gynecology with its ‘wild animal,’ as we have already seen. However, both of these writers employed the term in a way that was clearly meant to evoke physical movement. Soranus was directly concerned with the idea that the womb moved violently in the body, and Trota in De curis mulierum ( On Treatments for Women ) described the womb as ‘falling’ in various directions. To be a ‘wild animal’ in this context meant to move around unexpectedly and uncontrollably.

It is possible to find justifications for such a reading outside of the medical tradition. Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae famously defined wild animals similarly, stating that ‘they are termed wild ( ferus ) because they enjoy a natural freedom and are driven ( ferre ) by their own desires—for their wills are free and they wander here and there, and wherever their spirit leads, there they go’ (Isidore of Seville 2006 , 251). Isidore conflates the term fera with the more general ‘beast’ ( bestia ), which is defined by its violence—also fitting for the image of an unruly womb leaping around the body and causing harm, like a lunging predator. It is tempting to understand the term as purely taxonomic, simply separating the wild creatures from the domesticated ones. Other examples from the medieval period support this reading, for instance Peter Abelard’s commentary on Genesis, which focuses on literal explanations to the biblical texts, explains the meaning of bestias terrae (Genesis 1:25) as ‘ silvestres, ut feras .’ (Romig 1981 , 68). Abelard later explicates the distinction between domesticated animals (literally quadrupeds, quadrupedia ), and beasts of land or field, which are wild and are commonly called forest animals ( silvestria ) (Romig 1981 , 128).

From these examples ‘wild’ almost seems like a fixed category with a rigid and wholly negative meaning. Pierre-Olivier Dittmar argues that this understanding of beasts, either as bestia or fera , emphasizes the way these animals challenge what it means to be human. Bestial behavior, as a result, was understood as a ‘counter-model’ of civilized behavior (Dittmar 2007 , 154, 160–161). This dichotomic view of wild beasts and people maps neatly onto the distinction between sensory-motivated and rational behaviors, which are at times contrasted (Crane 2008 , 38–40). As expressed by the theologian and bishop of Paris, William of Auvergne (1180–1228), animals, being sub-rational, are completely subjugated to their desires, devoid of free will, and inherently inferior to people (Wei 2020 , 40, 53–55). In this context, characterizing the womb as feral seems like an entirely negative characterization, in line with other animal metaphors in medical literature. However, ‘feral’ and ‘wild’ were far from fixed categories in medieval thought, and the contrast between ferality and rationality was anything but stable. Susan Crane warns against searching medieval texts for strict taxonomies of animals, instead, she shows how bestiaries employed ‘wild’ as a flexible descriptor based on character rather than zoology. She further argues that rather than enforcing a dichotomy between reason and natural behavior, bestiaries often blur categorical differences between the two and even challenge the implicit hierarchy that prioritizes rational humans. The contrast, she claims, was employed ‘as an occasional claim but not as a working principle’ (Crane 2008 , 11, 42–44).

Just as he denigrated wild animals for their irrationality, William of Auvergne praised these creatures in a sermon written for the celebration of the second day after Easter. The bishop emphasizes the eternal love of God for his flock by contrasting it with the love of a mother for her children by citing Isaiah 49:15, ‘Can a mother forget the baby at her breast and have no compassion on the child she has borne? Though she may forget, I will not forget you!’ William further highlights the awesome strength of God’s love for his creation: ‘For a woman, at times, is corrupted from her own nature when she deserts her children and such things which are against the nature of forest beasts,’ but, according to William, God cannot be corrupted in such a way and will always respond to the pleas of those he has created (Alvernus ed. Morenzoni 2011, 166 trans. from Latin our own). William’s reference to fera silvestris rather than to specific animal species, like we find in Ambrose’s Hexameron, suggests that he wanted to highlight the ferality of the animals in question to his listeners, and that his argument hinged on this quality.

Irrationality and feral behavior were, after all, at the center of many contemporary discussions. In debating animals’ emotions, medieval scholars suggested that despite being irrational, animal souls could nonetheless operate in ways similar to human souls. Thus, for example, Thomas Aquinas followed an argument that first appeared in Avicenna’s De anima ( On the Soul ). Avicenna examined the force that spontaneously drives a ewe to fear a wolf, despite her lack of sufficient cognitive faculty for understanding the concept of ‘wolf,’ or to infer further about the wolf’s presence, or the appearance of danger and the need to flee. It is animals’ nature, according to Aquinas, which directs their emotional reaction, for, in contrast to humans, they cannot obtain judgement of basic beliefs (Perler 2018 , 41–42). When pondering the question of how certain animals know to perform different actions, like weaving silk in the case of spiders or swimming in the case of ducks, William of Auvergne concluded that this knowledge comes from a form of divine ‘illumination’ (Wei 2020 , 55, 61). Strictly speaking, this was not a form of rationality, but William conceded that nonhuman animals had abilities that were akin to the knowledge humans acquire with reason. This assertion not only challenged the assumed inferiority of irrational creatures, but it motivated William to argue that animals deserved admiration for their connection with the divine (Wei 2020 , 67–68, 72).

The various strains of these discussions and their treatment by Avicenna, William of Auvergne, Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274), and others go far beyond this article's remit. However, it is still important to note that they consider the faculties of the soul, specifically those related to the senses, estimation, and discretion, as key to understanding the nature of the sensitive soul and its shared animal/human traits. At the same time, these discussions also try to define the unique workings of the rational soul, which is only found in humans (and angels). Here, too, it is evident that thinkers of diverse backgrounds and training paid attention to animals and their affective relationships. As Dominik Perler showed in the case of Thomas Aquinas, the theologian used the example of wolves’ hostility to sheep, on the one hand, and protective attitudes to their young, on the other, to illustrate philosophical problems with absolute properties (Perler, 55). We see that the attention given by thinkers of diverse backgrounds and training to animals and their affective relationships—for example, in the comparison between the relationship of a wolf and their cub and that of a wolf and a sheep—accentuated the notion that parental love for offspring is fundamentally ingrained and requires hardly any cognitive processing. By focusing on the shared instinctive features of humans and beasts and emphasizing the connection between the feral and the divine, the fera silvestris could become a model for unspoiled human behavior, despite being an irrational creature. The usage of the metaphor, then, with its established associations of desire and nature, was far from simply derogatory in medieval discussions of animals and people. To become bestial, in some cases, could be understood as a call ‘to become truly natural in obeying God’s law,’ in Crane’s words ( 2008 , 28).

Contemporary musings about ferality and rationality shape the use of fera silvestris in Gilbert’s Compendium in a way that is notably distinct from its previous use in medical texts. In the most immediate sense, it becomes clear that even though Gilbert employs the same term Trota and Soranus used, he was not concerned with the question of the womb’s movement as they were. ‘Movement’ is secondary in his metaphor, which first and foremost discusses the womb’s capacity for emotions. To that end, he employs the term fera silvestris in a way that evokes debates about the soul and its faculties and animates the womb with senses and emotions. Gilbert’s metaphor of the beast thus links these two pains: the physical and the emotional, naturalizing the aches of miscarriage.

Emotion and metaphor: mother/womb

This brings us to a larger point about Gilbert’s importance in the wider history of gynecological metaphors. The womb’s pain in Gilbert’s metaphor is intertwined with natural maternal affection—;the type of affection that is idealized in animals and expected of human mothers. The womb nurtures, hugs, and enjoys. It performs these acts in such a way as to fulfill its Aristotelian aim. The womb was meant to carry the fetus, and the fulfillment of its designated function bestows satisfaction and contentment, while the absence or the unfulfilled task causes suffering and pain expressed in wild movement, but even these negative reactions are understood as natural and justified. This equation of role and fulfillment is used to describe the biological-technical process and is not necessarily associated with their personification. Similar physiological terminology appears in discussions of the womb’s part in sexual pleasure in the period (see Jacquart and Thomasset 1988 , 70–74; Cadden 1993 , 105–166). Gilbert’s choice of words recalls a semantic field of affection and maternal behavior that prompts the reader to notice that the process of evacuation and attendant pains is not merely physiological.

The link between the physical womb and the maternal role was already deeply drawn in a number of medieval languages, in which the word mother was etymologically (and audibly) close to the word womb, as in Latin matrix and mater , or in French matrice and mère . Often the word for mother became synonymous with womb (but not the other way around): in Castilian madre , in Middle English moder, and in Hebrew em . This linguistic proximity would at times confuse the copyists in their search for the correct reading of the text they were copying. For example, in some copies of Albert the Great’s commentary De animalibus ( On Animals ), the description of the procreation of various fish resulted in diverse readings of the following sentence: ‘It is possible to find the beleniz , like the fatigya next to their mothers, near their wombs-mothers ( matrices / matres ), as if they were moving and colliding inside the womb: and so it often occurs that the belloni fish escape from their mother who is angry with them because of the pain [they cause] her womb’ (Albertus Magnus 1916 , 480). In some of the translations of Gilbert’s Latin Compendium to late Middle English this linguistic overlap was even used to emphasize the double pain of both womb and mother:

Pain of the womb [ matrice ] comes from a stillborn child that is born before his time, as the mother/womb [ moder ] greatly likes and is comforted by the child within her, and when she loses it, she mourns and feels sorrow, just as a cow does when she loses her calf, and that sorrow is pain of the womb [ matrice ]. (Green and Mooney 2008 , 520; see also Cohen-Hanegbi 2019 , 126–127)